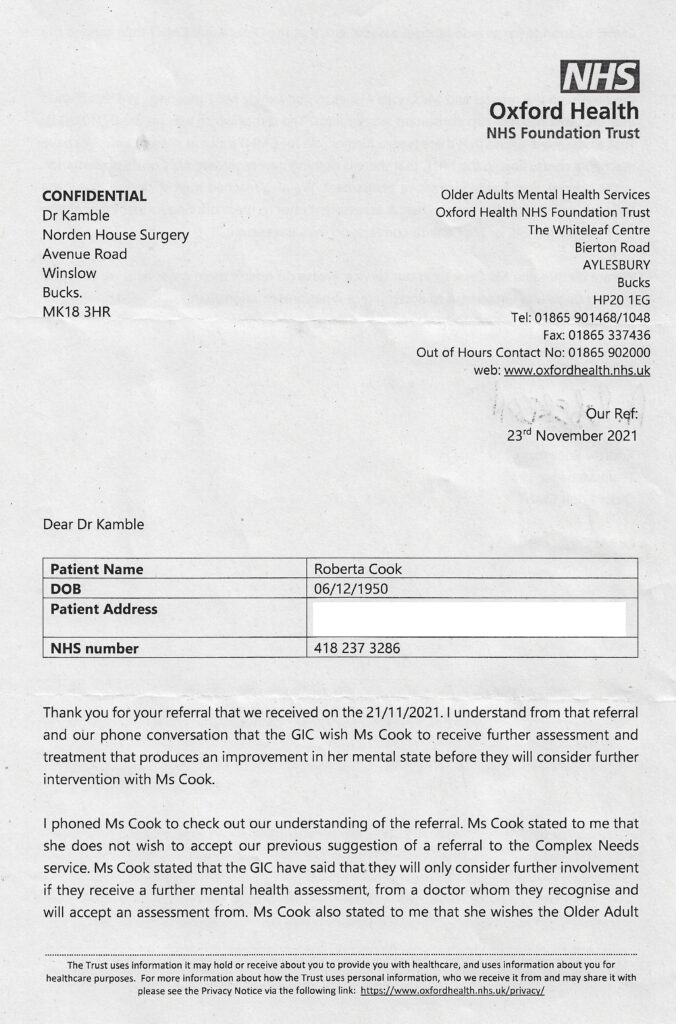

December 13th 2022

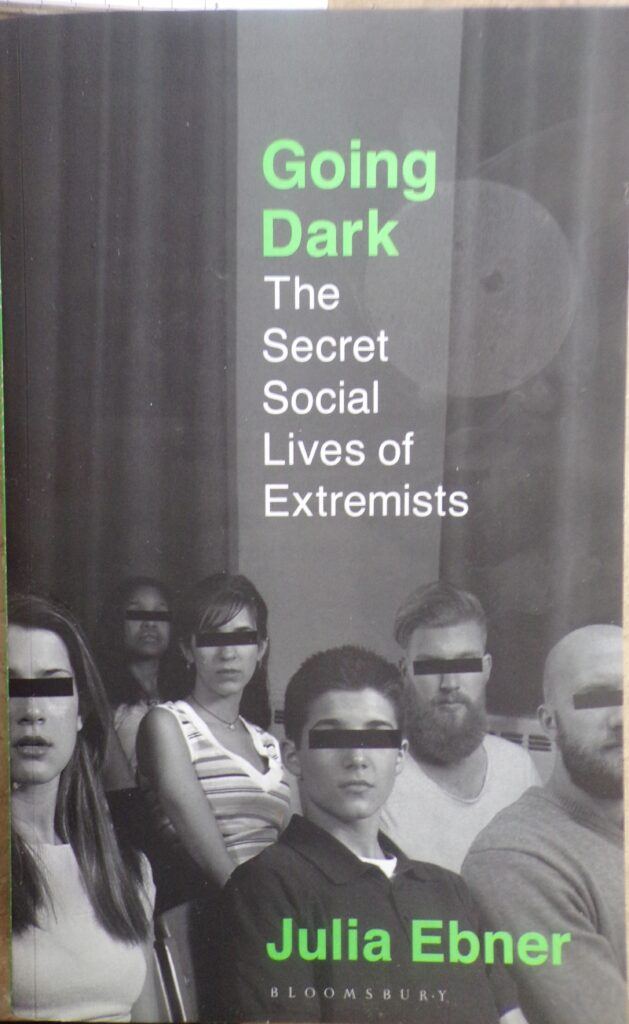

MP wrongly suggested 436 transgender women committed rape between 2012 and 2018, says Crown Prosecution Service

Bethany Dawson Apr 6, 2022, 4:57 PM

- Sir Bernard Jenkin MP said 436 transgender women committed rape between 2012 and 2018.

- The CPS has told Insider that this is not a correct reading of their data, and Jenkin is incorrect.

- One MP has called on Jenkin to withdraw his comments, saying he is “fanning the flames of hate.”

Top editors give you the stories you want — delivered right to your inbox each weekday. Email address By clicking ‘Sign up’, you agree to receive marketing emails from Insider as well as other partner offers and accept our Terms of Service and Privacy Policy. Sponsored Content by Twilio Meet 6 inspirational leaders creating a better future for developers

A Conservative MP wrongly suggested 436 transgender women committed rape between 2012 and 2018, the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) has confirmed.

Speaking at an International Women’s Day debate in the Houses of Parliament on 10 March, Sir Bernard Jenkin MP set out his concern that transgender women commit violence against cisgender women. He said:

“Nearly all violence against women is committed by men, but there is a new and growing category of violence against women committed by people who call themselves women but are biologically male. We should always respond positively to people with genuine gender dysphoria, and I deliver this speech with kindness in my heart, but the Sexual Offences Act 2003 defines rape as when a person “intentionally penetrates the vagina, anus or mouth of another person…with his penis” without consent.

The Crown Prosecution Service reports that between 2012 and 2018 more than 436 cases of rape were recorded as being committed by women. The penis is a male organ, so these rapes are committed by men presenting themselves as women.”

Comment Rape was significantly redefined by U.K’s New Labour Governments to include unwanted kissing or physical contact from men. In spite of significant evidence , violence from women on men and their childen is at least as high as that toward women from men. Women also exceed males in harming children. However , it is not taken seriously and usually regarded officially and colloquially, as the men provoking it. Again, evidence that women provoke a lot of domestic violence is ignored, the popular, official and media view being that women never lie. Police are under great pressure to accept this because political masters desperately compete for the feminist vote, which is what Patrick Jenkin is doing.

Feminists have an enormous problem with MTF Transsexuals. They are more comfortable with gay men who are non threatening and happy to be patronised by women. Hate speech only applies where it suits the PC consensus. Transwomen present competition ,often presenting a traditional feminine image, behaviour pattern and value system. Women led by feminists abhor that and have to fight.

There is also the problem that men are increasingly wary of dictatorial tyrannical know all self righteous feminism. So we have increasing MTF women ,along with male admirers. Parliament is riddled with opinionated feminists favourably represented by feminised elite media. Together , they viciously asert the view that only they must refine how males are redefined to suit their requirements. Men are required to change to fit with them in a society embracing feminism as a core value system. Social and economic consequences have been horrendous and on going -notably family collapse and rising youth suicide and mental illness.. R J Cook

September 25th 2022

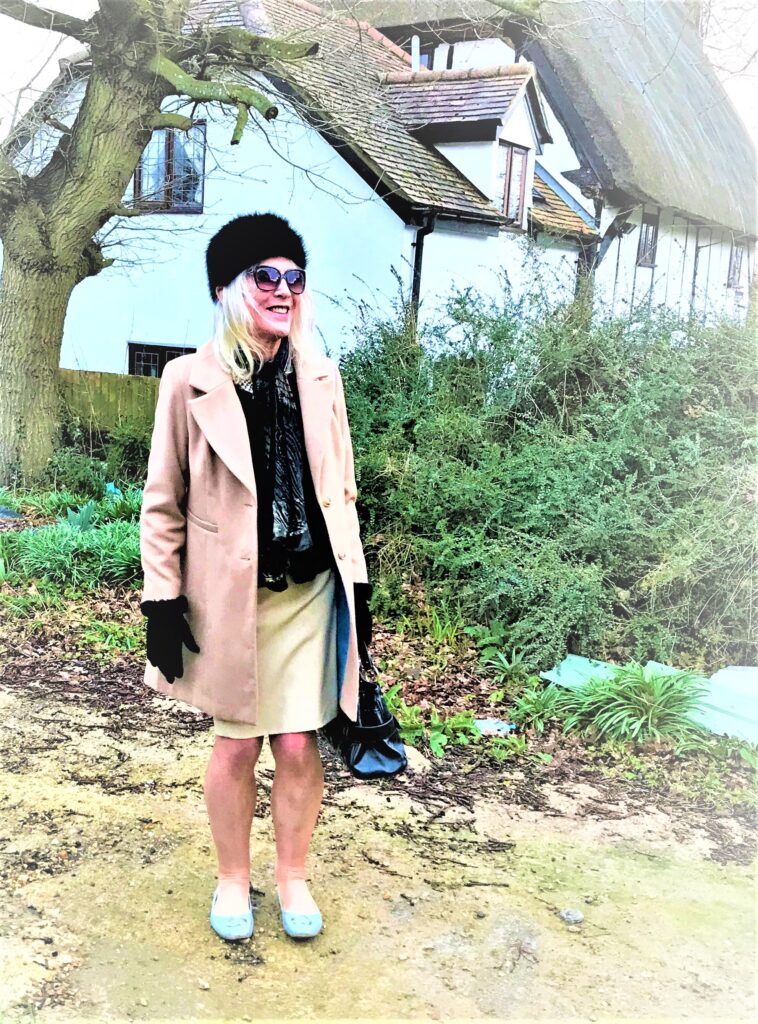

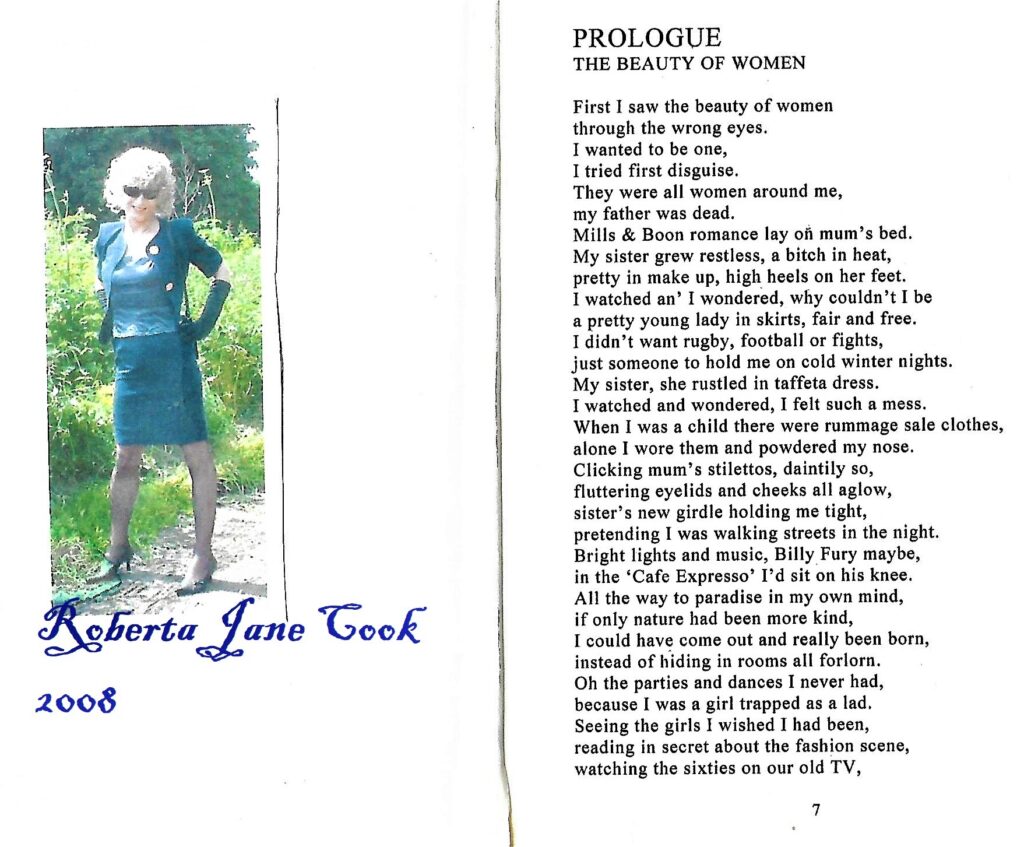

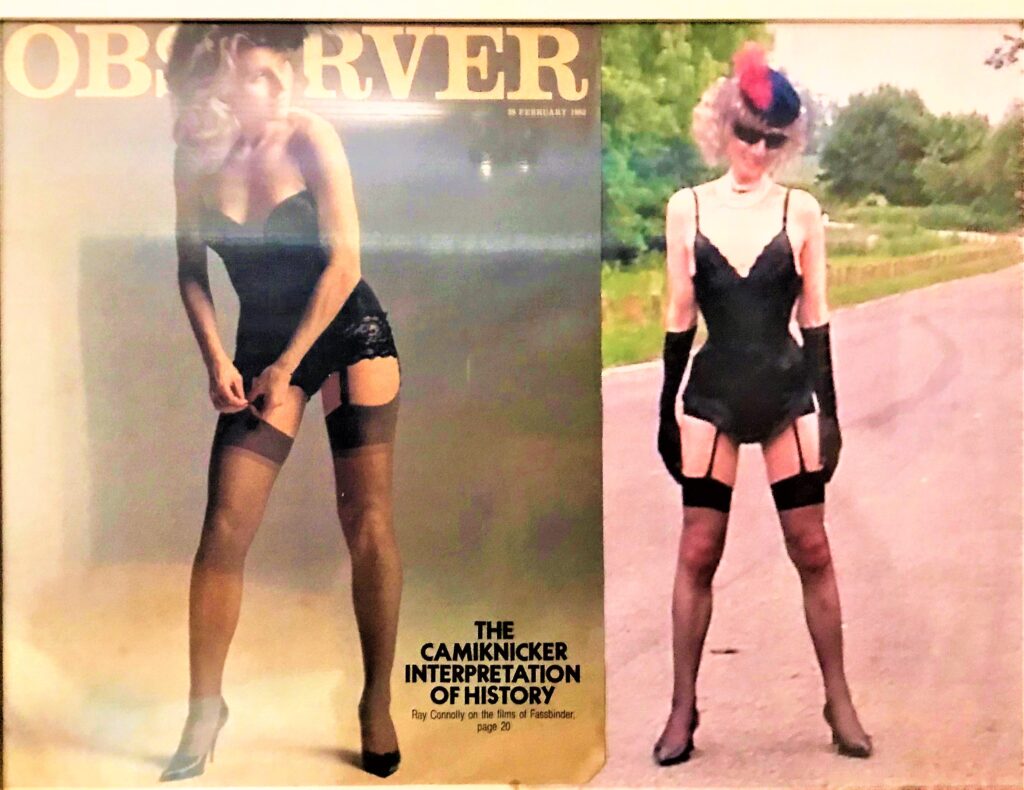

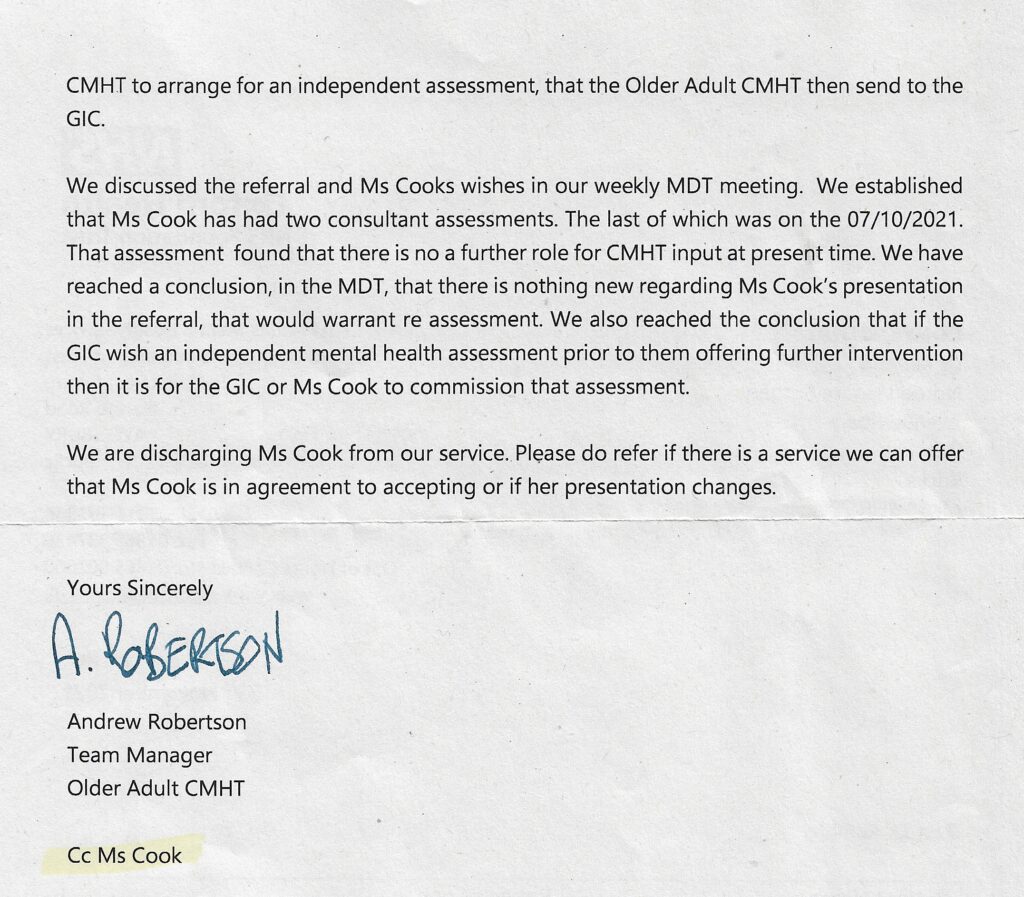

Transposing by Miss Roberta Jane Cook

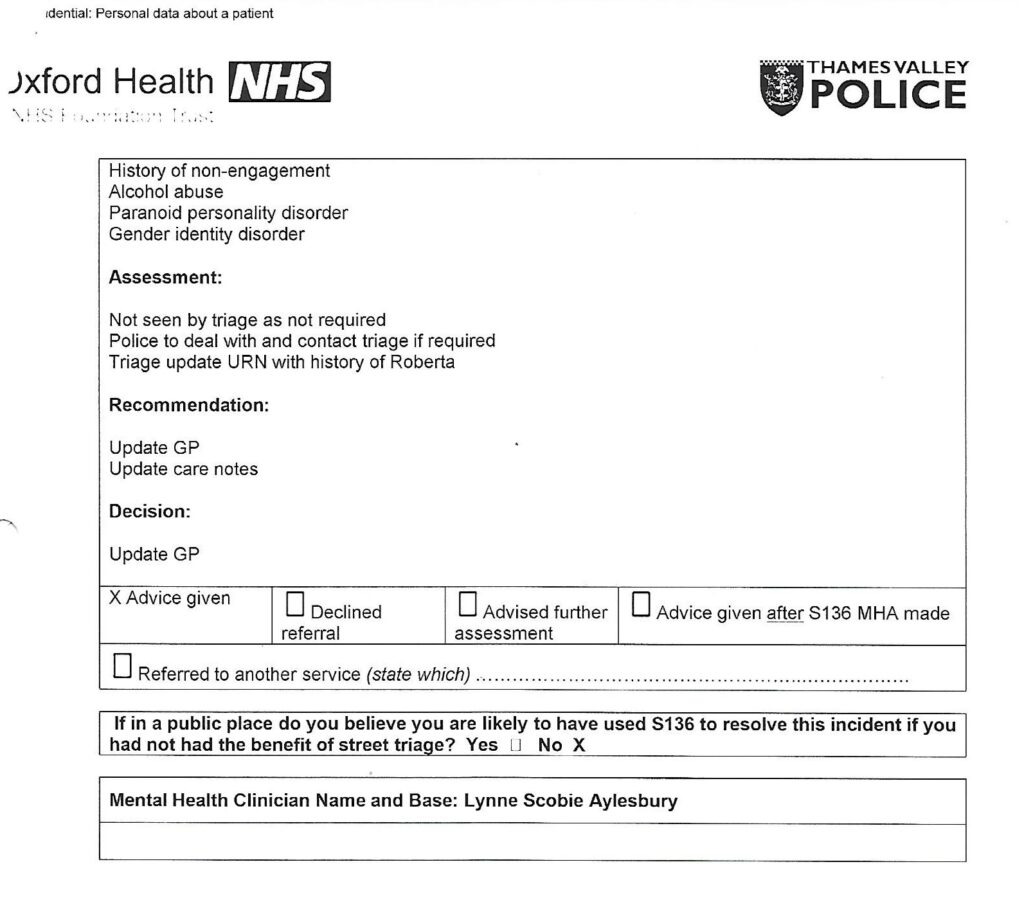

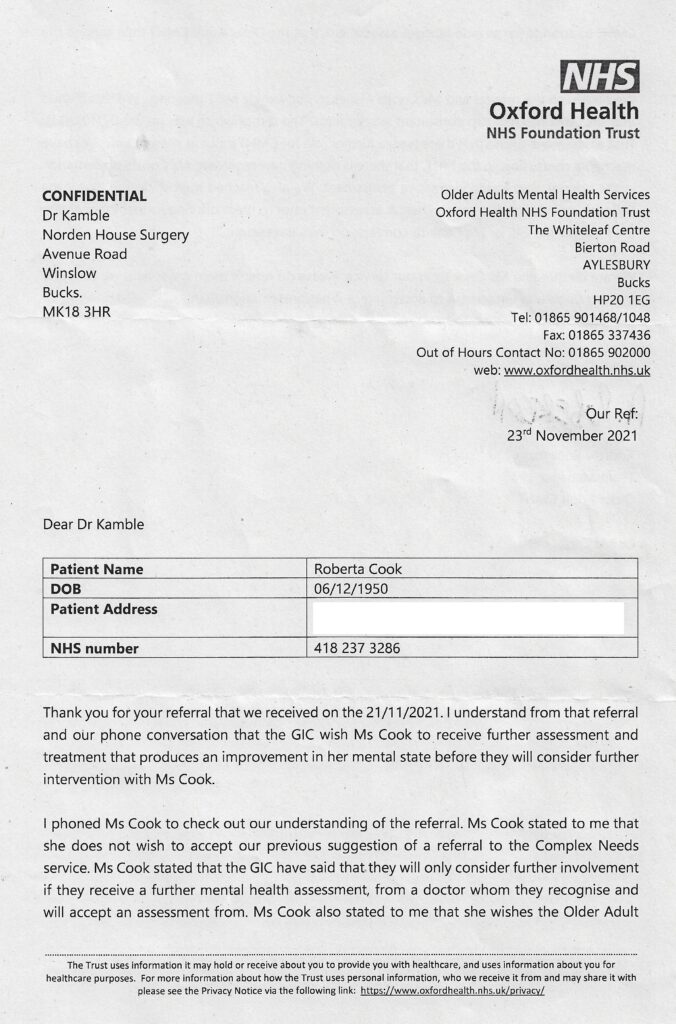

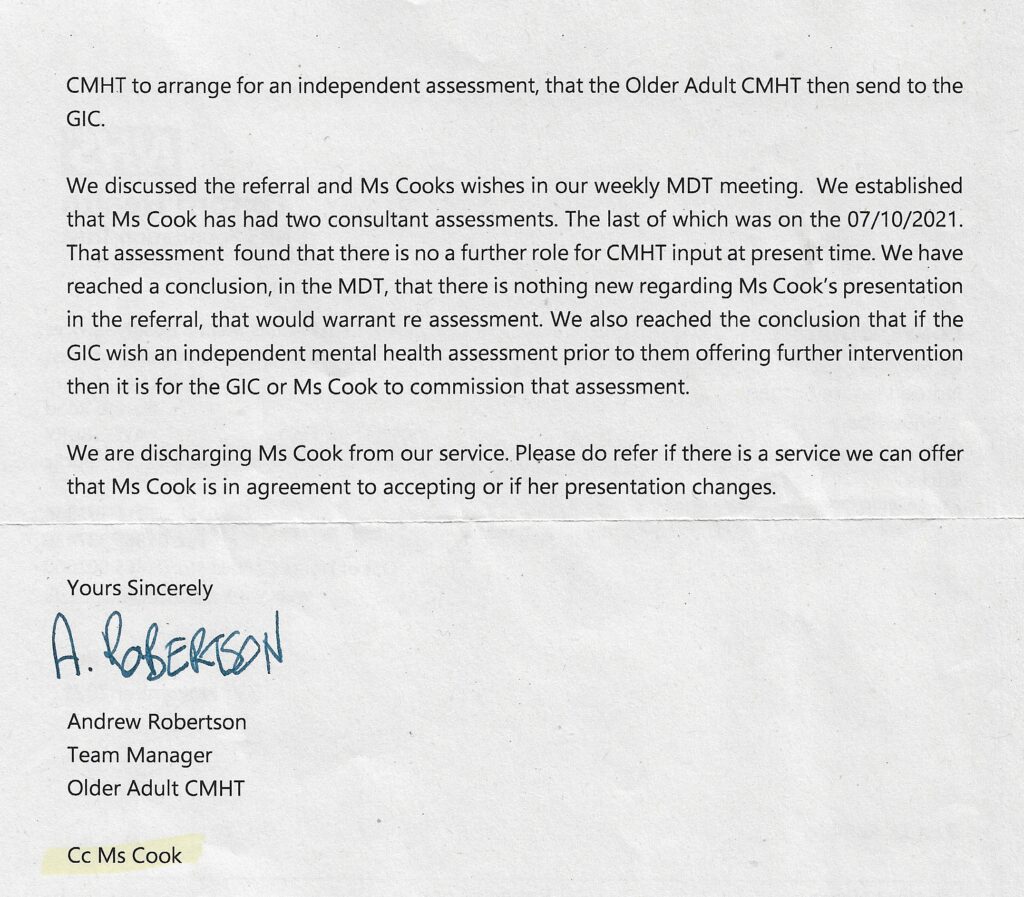

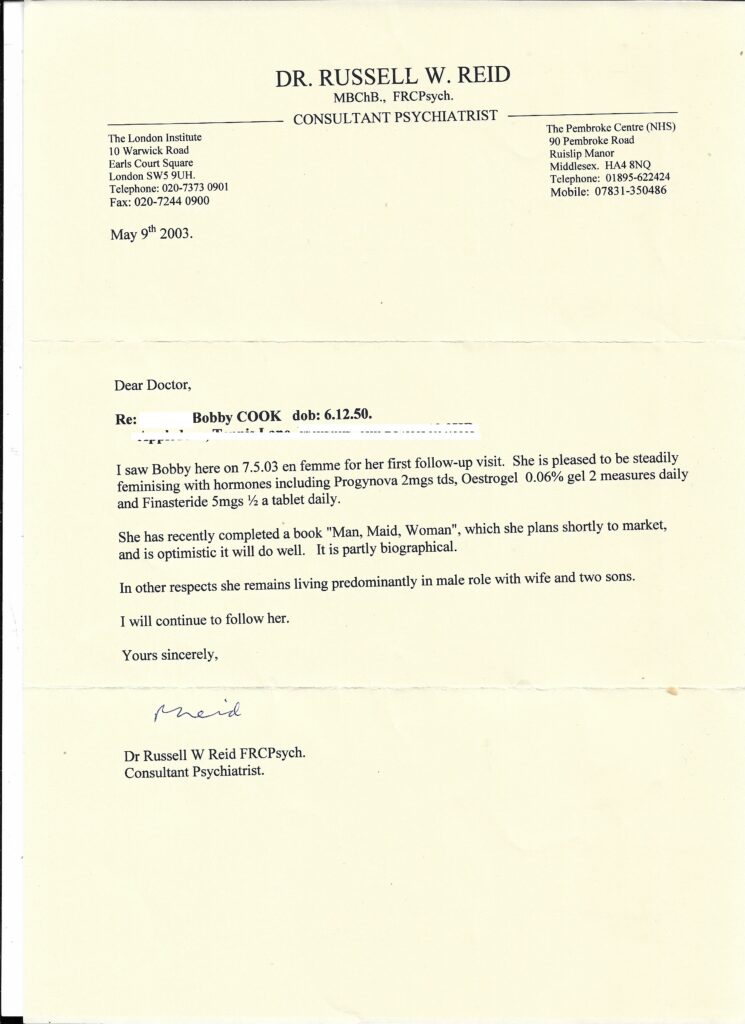

I suggest this picture purveys my claim to femininity as my true identity, truth and ultimate complex obvious need. Completion of sex cahnge was overdue and denied me when police told doctors lies that I had sent pictures of a private personal nature, porn videos which did not exist, offensive letters to sensitive parties accusing mysellf anonymously of working as a s ‘ gay escort’ in a home based brothel for my son and his associates. There was no evidence or sign of investigation. All was presented as truth to the GIC for the purpose of destroying my transgender credibility and keeping me under surveilance..

I, as did my ex wife, knew my marriage was over by 1988, but we have to be treated as freaks and forced to conform , as through devices like Myers – Briggs test to get a job.

I stayed married to protect my children in a world that sanctifies sis women regardless of what they do . These sis women perceive us trans ladies as a threat to their efforts to both masculinise their gender while behaving like the worst power maniacs and little Hitlers.

They can say what they like about us but want hate laws and restraining orders to keep themselves and ‘their children safe.’ They perpetuate the myth that sis women never lie, are always victims , care for children ( ironic an Irish woman recenly locked her toddlers into her car and set it on fire ) and fight for equal rights. If it had been a man, there would have been a national self righteous media outburst asserting the need to do more to control male violence It is against this background of liars , posers , manipulators and cheats that the Briggs- Myers job personality test should be judged.

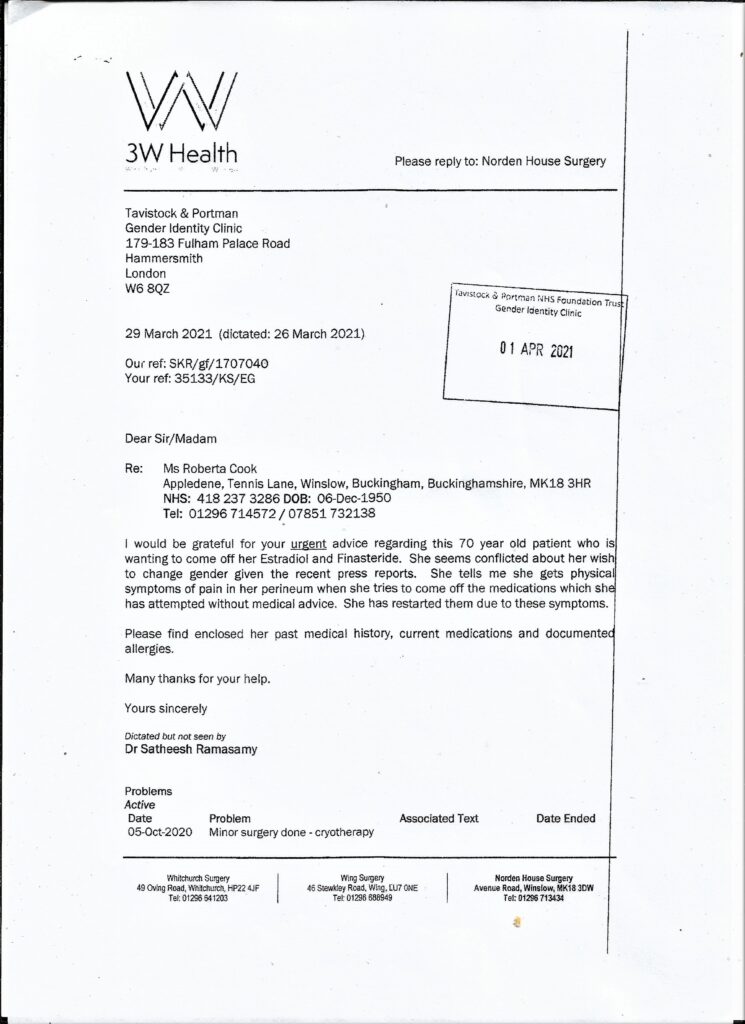

It is very difficult being a transwoman, especially when the police involeve themselves passing messages via the GP declaring me to be a paranoid schizophrenic bi polar delusional and not needing hospital yet but joint medical and police monitoring along with powerful anto psychotic drugs, with alarming side effects including bowel, bladder contro , balance , memory, speechl and dementia.

After nearly 3 years as a patient due for Gender Reassignment Surgery, this and my hormones were stopped, with alarming physical, psychological, social and economic consequences. The4 police for legal reasons I cannot discuss, have hammered home the view to all in sundry, including the medical professional who reported that I have a ‘secure female identity.’ am a fake, a TRANS POSER.

Asking how the relevant pyschiatrists who broke all the rules of diagnosis, did I become so labelled, there was stony silence and the offical reofcrd that I was’ more likely to die by misadventure than suicide.’ A report noted that ‘If Roberta saw all the records about her she would be very upset.’ Both my GP and the gender Identity Clinic have put in writing, and I have reecoded my GP telling me, that they need police permission to disclose them.

This permission as with all records on me has been denied. It is almost funny that they label me paranoid – the clinical definition being ‘abnormal suspicion’. Schizophrenia is multiple personality and hearing voices ( so which one of me is writing this and who is telling me what to write ?) , bi polarism is severe up and down mood swings, delusion is having no sense of reality. Reality was one of the big questions I had to consider when obliged to study philosopy during my first year at University of East Anglia, but these days the police decide what it is !

Added together it is a serious psychosis requiring mind numbing drugs. The GIC ( Gender Identity Clinic ) estimates 90% of its patients are mentally ill but less likely to commit suicide if they have sex change treatment. But the final diagnostician in my case is the police. To them I am a Transposer Transvestite who gets sexual kicks from wearing female clothes as was made clear to me by a party I cannot name, last June. But the source was evident laying on the party’s desk !”

September 19th 2022

Don’t Insist on Being Positive—Allowing Negative Emotions Has Much to Teach Us

Leaning into difficult feelings can help you find the way forward, according to a refreshing new wave of books, says Jamie Waters.

- Whitney Goodman

More from The Guardian

- Consumed by anxiety? Give it a day or two14,415 saves

- Silence Your Inner Critic: A Guide to Self-Compassion in the Toughest Times1,419 saves

- Why Your Most Important Relationship Is With Your Inner Voice3,156 saves

Advertisement

‘Complaining is natural because language converts a “menacing cloud” into “something concrete”. Photo by erhui1979/Getty Images

Eight years ago, when Whitney Goodman was a newly qualified therapist counselling cancer patients, it struck her that positive thinking was being “very heavily pushed”, both in her profession and the broader culture, as the way to deal with things. She wasn’t convinced that platitudes like “Look on the bright side!” and “Everything happens for a reason!” held the answers for anyone trying to navigate life’s messiness. Between herself, her friends and her patients, “All of us were thinking, ‘Being positive is the only way to live,’ but really it was making us feel disconnected and, ultimately, worse.”

This stayed with her and, in 2019, she started an Instagram account, @sitwithwhit, as a tonic to the saccharine inspirational quotes dominating social media feeds. Her posts included: “Sometimes things are hard because they’re just hard and not because you’re incompetent…” and “It’s OK to complain about something you’re grateful for.” It took off: the “radically honest” Miami-based psychotherapist now has more than 500,000 followers.

Goodman’s 2021 book, Toxic Positivity, expands on this thinking, critiquing a culture – particularly prevalent in the US and the west more broadly – that has programmed us to believe that optimism is always best. She traces its roots in the US to 19th-century religion, but it has been especially ascendant since the 1970s, when scientists identified happiness as the ultimate life goal and started rigorously researching how to achieve it. More recently, the wellness movement – religion for an agnostic generation – has seen fitness instructors and yogis preach about gratitude in between burpees and downward dogs. We all practise it in some way. When comforting a friend, we turn into dogged silver-lining hunters. And we lock our own difficult thoughts inside tiny boxes in a corner of our brains because they’re uncomfortable to deal with and we believe that being relentlessly upbeat is the only way forward. Being positive, says Goodman, has become “a goal and an obligation”.

Toxic Positivity is among a refreshing new wave of books attempting to redress the balance by espousing the power of “negative” emotions. Their authors are hardly a band of grouches advocating for us to be miserable. But they’re convinced that leaning into – rather than suppressing – feelings, including regret, sadness and fear brings great benefit. The road to the good life, you see, is paved with tears and furrowed brows as well as smiles and laughter. “I think a lot of people who focus on happiness, and the all-importance of positive emotions, are getting human psychology wrong,” says Paul Bloom, a psychology professor at Yale and the author of The Sweet Spot, which explores why some people seek out painful experiences, like running ultra marathons and watching horror movies. “In a life well lived, you should have far fewer negative than positive emotions, but you shouldn’t have zero negative emotions,” adds Daniel Pink, the author of The Power of Regret. “Banishing them is a bad strategy.”

The timing of these new works – which also include Helen Russell’s podcast (following her book of the same name) How To Be Sad – is no coincidence. In light of the pandemic and now the conflict in Ukraine, it seems trite to suggest a positive outlook is all we need. Strong negative emotions – fear, anxiety and sadness – are a natural response to what’s happening around the world right now and we shouldn’t have to deny them.

These authors want you to know that “negative” emotions are, in fact, helpful. Russell talks about sadness being a “problem-solving” emotion. Research from the University of New South Wales shows that it can improve our attention to detail, increase perseverance, promote generosity and make us more grateful for what we’ve got. “It’s the emotion that helps us connect to others,” she adds. “We’re nicer, better people in some ways when we are sad.”

It’s tougher making an argument for regret, which might be the world’s most maligned emotion, but Pink is game. From a young age we are instructed to never waste energy on regrets. The phrase “No regrets” is inked into arms and on to bumper plates and T-shirts. Seemingly every famous person has a quip about living without regrets (I would know: as someone who tends to linger on thoughts of what might have been, I’ve read them all). Pink says we’re getting it all wrong. “A ‘No regrets’ tattoo is like having a tattoo that says ‘No learning’,” says Pink, who was also a speechwriter for Al Gore, speaking from Dallas, Texas. He became interested in this topic because he couldn’t shake his own regrets about the fact that, while a university student, he wasn’t kind to fellow pupils excluded at social events. “If it has bothered me for a month, a year, or in this case 20 years, that’s telling me: ‘Hey, you might not realise it, but you care about kindness,’” he says. “Regrets clarify what matters to us and teach us how to do better. That’s the power of this emotion – if we treat it right.”

The problem? We’re not taught how to effectively process these difficult emotions. A good starting point is to familiarise ourselves with these feelings by acknowledging them and sitting with them for a beat. That takes practice, says Goodman. “It can include learning how your emotions feel in your body, and what to call them. When we’re able to put a name to a feeling, it makes it less scary. And when something is known, we can figure out what we want to do with it.”

Telling others about it lightens the weight. Complaining is perfectly natural, says Goodman. And articulating it helps us pinpoint what it is that’s bothering us, because language converts this “menacing cloud” into “something concrete”, says Pink. That disclosure could be to a friend, therapist or total stranger. In his Regret Survey, 18,000 people anonymously shared their biggest regrets, while Russell suggests a “buddy” system, in which you make a reciprocal agreement with someone to talk about your worries without interruption. (A note, if you are comforting a friend: listen and ask questions rather than immediately reaching for pick-me-ups.)

Your next step will likely depend on the nature – and severity – of the emotion. To help us sit with sadness, Russell advocates being in nature. Cultural pursuits can help, too. “It sounds a little ‘woo’, but there are lots of studies about the effectiveness of reading therapy and looking at a piece of art – and how music can change our moods,” she says. “Sad music can act as a companion when we’re feeling sad, rather than making us feel lower. I do think it’s liberating when you finally kind of surrender to it all.”

Pink, whose approach is a little more structured, differentiates between regrets of action (wrongs you’ve committed) and inaction (opportunities not seized). For both, you must comfort yourself with the knowledge that everyone has regrets – and recognise that that single thing doesn’t define you. “Don’t look at a mistake as St Peter at the gate passing final judgment on your worth,” he says, but as “a teacher trying to instruct you.” He recommends stepping outside yourself and considering what you would recommend a friend do in a similar situation, whether that’s making amends for past acts, grasping a new opportunity, or ensuring you don’t make a similar misstep in the future.

Crucially, processing negative emotions “should all feel somewhat productive in the end”, says Goodman. Meaning: instead of ending up in a funk of wallowing, with your feelings replaying on a loop, “the wheels are turning, you’re making connections, you’re figuring things out,” she says. That doesn’t mean you need to come out of it feeling happy, or with a neat fix. “Sometimes you just get to a place where you say, ‘That was really hard, and now it’s over or now I’m not dealing with that any more’,” says Goodman. “And if it comes up for me again, I’ll deal with it.”

Leaning into negative thoughts should ultimately leave you with a sense of fulfilment. While we might instinctively think that filling our days solely with joy and excitement is the dream, “if we want to live a meaningful and purposeful life, a lot of pain is going to be part of it”, says Bloom. “What I really want is for people to be able to enjoy the full range of the human experience,” adds Goodman. Armed with the knowledge that you can do it in a methodical way, don’t be afraid to let the darkness in.

September 10th 2022

Full text links

Actions

Share

Page navigation

- Title & authors

- Abstract

- Comment in

- Similar articles

- Cited by

- Publication types

- MeSH terms

- Personal name as subject

- Related information

- LinkOut – more resources

J Psychiatr Pract

. 2012 May;18(3):221-4. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000415080.51368.cf.

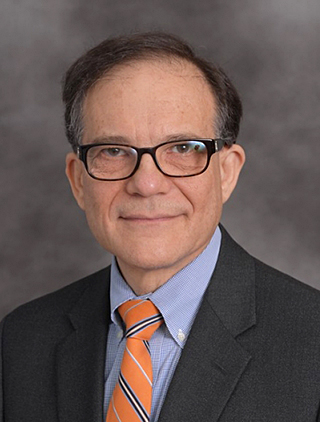

Inevitable suicide: a new paradigm in psychiatry

Benjamin J Sadock 1 Affiliations

- PMID: 22617088

- DOI: 10.1097/01.pra.0000415080.51368.cf

Abstract

The author suggests that a new paradigm may be needed which holds that some suicides may be inevitable. The goal of this paradigm would be to diminish the sense of failure and inadequacy felt by many psychiatrists who experience the suicide of a patient and to increase understanding of the unique biopsychosocial profile of those whose suicides appear to be inevitable. The author stresses that this proposed paradigm should not be misconstrued as therapeutic nihilism but rather should serve to stimulate efforts to treat this patient population more effectively. Risk factors that place individuals at high risk for suicide are reviewed, including presence of a mental illness, genetic predisposition, and factors such as a history of abuse, divorce, unemployment, male gender, recent discharge from a psychiatric hospital, prior suicide attempts, alcohol or other substance abuse, a history of panic attacks, and persistent suicidal thoughts, especially if coupled with a plan. The author notes that, in those suicides that appear to have been inevitable, risk factors are not only numerous but at the extreme end of profound pathology. The example of Ernest Hemingway is used to illustrate how such a combination of risk factors may have contributed to his eventual suicide. Psychiatrists, like other doctors, may have to acknowledge that some psychiatric disorders are associated with a high mortality rate as a natural outcome. This could lead to heightened vigilance, a more realistic view of what can and cannot be achieved with therapy, and efforts to improve the quality of life of patients at high risk for suicide with the goal of reducing this risk and prolonging their lives. (Journal of Psychiatric Practice 2012;18:221-224).

Comment in

- Comment on “inevitable suicide”. Ellis TE. J Psychiatr Pract. 2012 Sep;18(5):318-9; author reply 320. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000419813.52881.52. PMID: 22995956 No abstract available.

- Consequences of “inevitable suicide”. Maniam T. J Psychiatr Pract. 2012 Sep;18(5):319; author reply 320. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000419814.30011.c0. PMID: 22995957 No abstract available.

Similar articles

- Prevention of suicide and attempted suicide in Denmark. Epidemiological studies of suicide and intervention studies in selected risk groups. Nordentoft M. Dan Med Bull. 2007 Nov;54(4):306-69. PMID: 18208680 Review.

- Ernest Hemingway: a psychological autopsy of a suicide. Martin CD. Psychiatry. 2006 Winter;69(4):351-61. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2006.69.4.351. PMID: 17326729

- Adolescent suicide. [No authors listed] Rep Group Adv Psychiatry. 1996;(140):1-184. PMID: 8721288

- [In-patients suicide: epidemiology and prevention]. Martelli C, Awad H, Hardy P. Encephale. 2010 Jun;36 Suppl 2:D83-91. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2009.06.011. Epub 2009 Sep 26. PMID: 20513465 Review. French.

- The suicide of Anne Sexton. Hendin H. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1993 Fall;23(3):257-62. PMID: 8249036

September 9th 2022

How to Spot the Potential Warning Signs of Suicide

Suicide expert Dr. Mark Russ on recognizing suicidal behavior, and how to help someone who is suffering and may be contemplating taking their own life.

14 Min Read •Mental Health • Story By Courtney Allison

Despite growing public attention and efforts to curb the country’s suicide rate, the statistics are sobering: Suicide is the 10th-leading cause of death in the United States, according to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. In 2017, more than 47,000 Americans died by suicide, a 33% increase since 1999.

“Suicide is both a public health problem and, of course, an extremely individual one,” says Dr. Mark Russ, vice chair for clinical programs and medical director at NewYork-Presbyterian Westchester Division. “It’s critically important to continue to raise public awareness of suicide and suicide risk to try to get our arms around this, to do more research to understand the underpinnings of suicidal behavior, and educate people as best we can, including how to intervene on the level of families, schools, employers, and the medical community.”

Stressful life events are unavoidable, but it’s important to remember that painful feelings will not last forever, Dr. Russ emphasizes.

“I think many people feel that what they are feeling in the moment they will always be feeling, and therefore ‘I need to end this in some way,’” he says. “That is not true. We know that moments of emotionally intensely painful feeling tend to come and go. They don’t last forever; that is just sort of the way the brain works. Sometimes, just letting people know that what they are feeling now is not something they’re going to need to bear forever can help — that even if they do nothing, in time, they are likely to feel better.”

How do you know if someone you love is considering taking their life? And is there a way to help? Health Matters spoke with Dr. Russ to better understand what may drive someone to take their life, and potential warning signs of suicide.

Why do you think the suicide rate is rising?

Dr. Russ: It’s unclear why the rate is increasing. It could have to do with more people reporting it, or societal stressors. Some have speculated that it could be related to the opioid crisis, social media, availability of information, bullying, or copycatting. Financial concerns are also a huge stressor for many people.

Who is most at risk?

The rates are rising in middle-aged individuals, particularly among white men, as well as adolescents and young adults. There are also increases among the elderly and the African American community.

We can only speculate, but for a middle-aged man it could have something to do with financial stressors, phase of life, the prospect of losing one’s job, or actually losing one’s job, retirement without adequate resources, or interpersonal issues involving family or divorce. For young people, possible factors include social media stress in terms of bullying, and tremendous social stress around getting into and succeeding in college and beyond.

Suicide is highest in people with existing mental and psychiatric disorders. We believe that there is a genetic component to suicide risk, and we know from studies that suicide can run in families.

What could trigger suicide?

Any kind of a loss is potentially a trigger for thinking about ending one’s life. It’s important to note that there is no absolute scale for loss. You can’t judge the meaning or impact of a loss to an individual. A circumstance or event that one person might regard as relatively trivial may be extremely impactful to an individual based on their experience, their interpersonal dynamics and who they are in the world. Some people may be very sensitive to humiliation or to being slighted. One person may think that’s just a part of life, but for another person it may be devastating.

“Struggling with depression, anxiety, or having thoughts of suicide is not uncommon, yet many people seem to distance themselves from it — perhaps because it’s not the way that people want to see themselves.”

— Dr. Mark Russ

What are the warning signs that someone may be considering suicide?

- A change in someone’s mood or behavior, particularly along depressive and anxious lines, or isolating themselves. This can come across as either a sad mood, a feeling of disconnection, or social withdrawal. People at risk for suicide may isolate themselves. They may be quieter or not enjoy things the way they used to. Adolescents who used to love to engage in sports or play video games may stop doing that. If you get the sense that they are lacking pleasure in life, that is an extremely important warning sign.

- Any statements that express a sense of hopelessness, helplessness, or worthlessness are evidence the individual may be becoming depressed. People may make a direct or indirect comment about suicide. Often, they may use euphemisms, like “I can’t take this anymore,” “I’m at the end of my rope,” “I want to throw in the towel,” or “Not sure how much longer I can go on.”

- Changes in intake of alcohol or use of illicit drugs.

- Signs of intense agitation, anxiety, or feelings of tremendous inner pain. This is an extraordinarily important warning sign of suicide because it may suggest that they are going to act soon.

What do you do if you see these warning signs of suicide?

Awareness is most important. People may deny that they or a loved one could be considering suicide because it’s too painful a thought. The natural tendency is to minimize symptoms and risks when they see them in other people. A loved one, for example, who has just suffered a traumatic life event, or experienced a situation that is painful, problematic, or difficult, might be overwhelmed by it and might be thinking that this is not something they can take anymore. The first step is to consider the possibility that suicide is among the potential outcomes of the situation and to listen very carefully.

How can you be a good listener?

Being a good listener can be tough, and it’s what we in behavioral health spend many years of training to do, because the natural inclination for most people is to jump in and share their experiences, give advice, and make judgments, all of which may not really be helpful in trying to help somebody who may be going through a very, very tough time.

- Keep your ears open and resist the temptation to talk a lot. Be present for the person and don’t interject with “quick” or “easy” solutions. Understand that if there were a quick and easy solution, this person would likely have already thought of it.

- Convey a sense of caring and interest. This can be done nonverbally and verbally, but try to provide a validation and acknowledgment of their current situation without making a judgment about it. Show that you see they are extremely depressed or despondent, and ask if they can tell you more about it.

- Ask questions that are open-ended and allow the person to talk as much as possible. Allow periods of silence. It conveys a respect for the person and an interest, that you’re willing to forgo your own needs in the moment for the sake of helping them. It’s not easy to do, but important.

- Create the time and space for someone to open up. You want to create a space that is private and give them enough time to talk.

What else can someone do to help if they suspect someone is considering taking their life or see a potential warning sign of suicide?

It’s OK to come out and ask “Are you feeling suicidal?” It’s not going to put the idea in their head if it wasn’t there before. Some may say they don’t have suicidal thoughts because it may be too painful to admit or it may be embarrassing because of the stigma associated with mental illnesses and suicide. Sometimes, it’s better to ease into the question by using terms that are less charged, like “Are you feeling overwhelmed?,” “Are you feeling that you can’t go on?,” or “Are you feeling at the end of your rope?” The idea is to normalize the experience and show that it’s understandable for someone who has gone through something difficult to have these thoughts.

What else is important to know?

Getting someone professional help is critical. You don’t want to be in a situation where you are the lifeline for another human being. That is fraught with danger for that person and for you. Even if the person doesn’t kill themselves, they put you in an untenable situation that you’re not prepared for and will likely cause a great deal of anxiety for you. The best thing you can do is whatever you can to get that person into treatment. It may range from providing a suicide hotline number to actually calling the police and an ambulance to bring them to the emergency room, depending on the acuity of the circumstance.

What if someone has ongoing feelings of suicide?

Often, suicidal feelings can last a long time and be chronic. In addition to treatment, it’s important to create a safety plan. There should be a very clear, and preferably written, point-by-point plan of what a person will do if they feel suicidal. This is hopefully done in the context of treatment, but it’s important for the family to be aware of it whenever possible. The plan can include anything from providing a suicide hotline number to engaging in coping mechanisms they’ve learned as part of therapy, going to an ER, or calling a therapist, friend, or parent. Coping skills may include distracting behaviors, like walking around the block, taking a bath, or watching a funny movie — whatever seems to work for that individual. But a list of activities and steps that they are going to take before they act or harm themselves is useful and important.

Even if they are not suicidal in the moment, these feelings tend to recur. We should have the expectation that they’re going to feel this way again and help them anticipate the circumstances under which these thoughts or feelings are likely to emerge. A young adult with a history of becoming suicidal after they fail a test may not feel suicidal now, but might if they fail another test. Knowing the steps to take to help in the moment to get over the crisis is extremely important.

Is suicide an impulsive act?

Not always. Some people think about suicide for a very long time and plan carefully and basically make a decision that they feel is rational, although others would not agree, that their life is just not worth living. Others may be extremely impulsive, and the suicidal act may come at a moment of heightened emotion, in particular heightened anxiety and this sense of what we call psychic angst — pain in your being that just feels unbearable in the moment and may push someone to do something impulsively. Then, of course, there’s everything in between.

Can you predict who will take their life?

We cannot predict who is going to die by suicide. Most people who experience or exhibit warning signs of suicide don’t take their lives. There are many risk factors, but there is a lack of specificity in those risk factors. Many people get depressed or go through periods of hopelessness. For statistical reasons having to do with the relative infrequency of suicide and lack of specificity of any risk factor or group of risk factors related to suicidal behavior, it makes it impossible to predict who will die by suicide.

There is no blood test. There is no brain scan. There is no psychological test that can tell us if and when an individual will engage in suicidal behavior. We look for triggers and warning signs that have been associated with suicide risk in vulnerable individuals because it makes common sense to do so and can save lives. But in the end, we don’t know what is in the mind of that person who ultimately decides to take their own life. We don’t know that final thought because it’s never available to us. Because of that, there’s a certain degree of humility that I think all of us who work with people who struggle with suicidal feelings have to accept and understand.

Is there still a stigma around mental illness and suicide?

I think it’s getting better very slowly, but it is still a huge problem. Efforts of organizations like the National Alliance on Mental Illness are making an impact, and public figures coming out and sharing their mental health struggles helps too. But I think that the stigma remains a problem, particularly in some communities more than others. When there are cultural prohibitions or consequences to having a mental illness or getting treated for one, it makes it that much more difficult to access care.

Struggling with depression, anxiety, or having thoughts of suicide is not uncommon, yet many people seem to distance themselves from it — perhaps because it’s not the way that people want to see themselves. The sense of emotional well-being is so closely connected to who you are in the world. It’s different than if you have pneumonia or diabetes, if something happens to you — somehow the idea of mental illness isn’t viewed the same way, perhaps because it’s so closely aligned with a sense of self and identity — even though these are brain diseases.

How can people who have lost someone to suicide cope?

Be aware of your feelings and understand and accept the fact that you are going to have very strong feelings about what happened. That’s normal and appropriate, and you will need support. The extent of that support may be limited or may be extensive in terms of getting into therapy.

There is no constructive role for guilt or self-blame — there has already been one casualty, and we need not create any more. Feelings of guilt, loss, anger, and, of course, tremendous sadness are all natural feelings that can be dealt with and understood in the context of the circumstance.

If you are in crisis, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255), or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741.

Additional Resources

- For additional resources on suicide prevention, visit the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, New York State Suicide Prevention, and the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

September 6th 2022

déjà vu

The Search for Scientific Proof for Premonitions

In the 1960s, a British researcher launched one of the largest ever studies of people who believed they could see the future.

Ron Burton/Mirrorpix/Getty ImagesChildren looking over Aberfan, Wales, in the wake of the disaster there in 1966

Ron Burton/Mirrorpix/Getty ImagesChildren looking over Aberfan, Wales, in the wake of the disaster there in 1966

When it finally happened, shortly after nine o’clock in the morning on October 21, 1966—when the teetering pile of mining waste known as a coal tip collapsed after days of heavy rain and an avalanche of black industrial sludge swept down the Welsh mountainside into the village of Aberfan, when rocks and mining equipment from the colliery slammed into people’s homes and the schools were buried and 116 young children were asphyxiated by this slurry dark as the river Styx—the anguished public response was that someone should have seen this disaster coming, ought to have predicted it.

Someone did.

Or at least, they claimed they had. Shortly after the tragedy at Aberfan, several women and men recalled having eerily specific premonitions of the event. A piano teacher named Kathleen Middleton awoke in North London, only hours before the tip fell, with a feeling of sheer dread, “choking and gasping and with the sense of the walls caving in.” A woman in Plymouth had a vision the evening before the disaster in which a small, frightened boy watched an “avalanche of coal” slide towards him but was rescued; she later recognized the child’s face on a television news segment about Aberfan. One of the children who died had first dreamt of “something black” smothering her school. Paul Davies, an 8-year-old victim, drew a picture the night before the catastrophe that showed many people digging in a hillside. Above the scene, he had written two words: The End.

Premonitions this dramatic and alarming are likely rare. But most of us have experienced odd coincidences that make us feel, even for an instant, that we have glimpsed the future. A phrase or scene that triggers a jarring sensation of déjà vu. Thinking of someone right before they text or call. Inexplicably dreaming about a long-lost acquaintance or relative only to wake and find that they have fallen ill or died. It’s mostly accepted that these are not really forms of precognition or time travel but instead fluky accidents or momentary brain glitches, explainable by science. And so we don’t give them a second thought or take them that seriously. But what if we did?

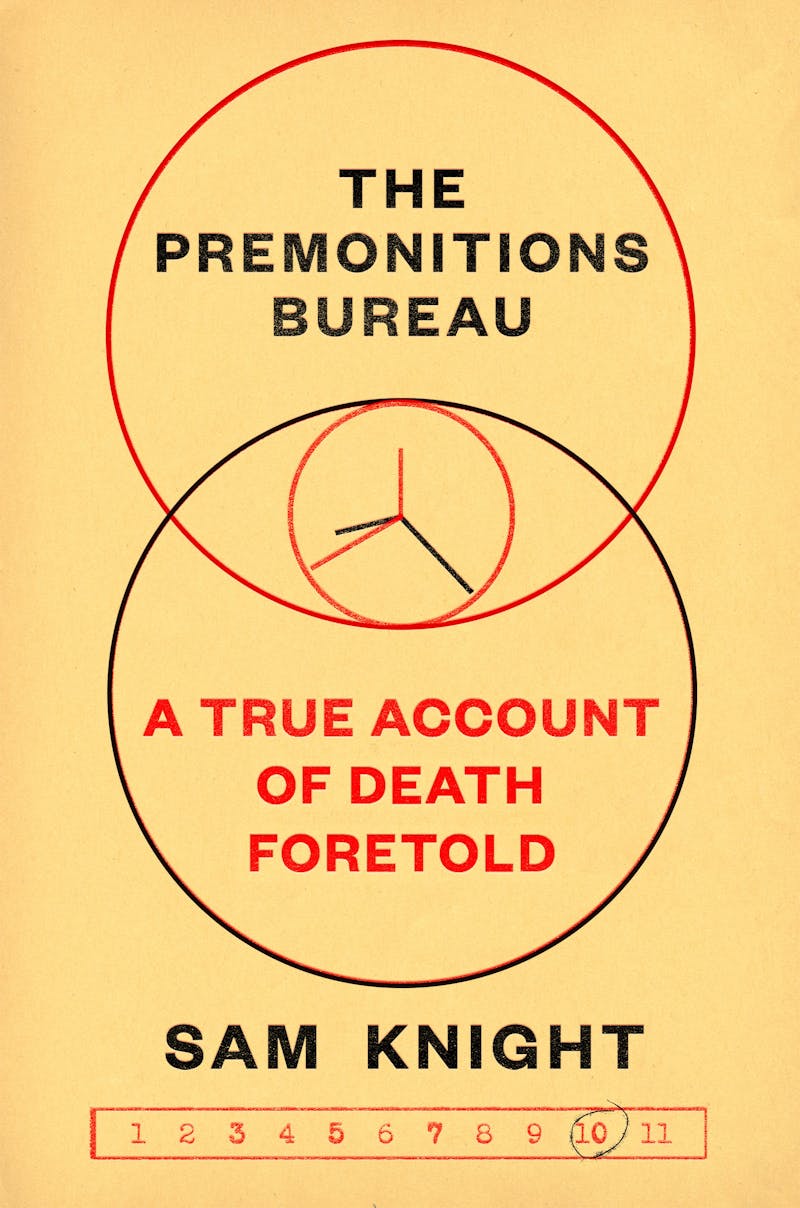

The Premonitions Bureau, an adroit debut from The New Yorker staff writer Sam Knight, draws us into a world not that far gone in which psychic phenomena were yet untamed by science and uncanny sensations still whispered of the supernatural, of cosmic secrets. Knight’s book registers the spectral shockwaves that rippled out from Aberfan through the human instrument of John Barker, a British psychiatrist who began cataloguing and investigating the country’s premonitions and portents in the wake of the accident. Barker spent his career seeking out the hidden joints between paranormal experience and modern medicine, asking scientific questions about the occult that we have now agreed no longer to ask. In Knight’s skillful hands, the life of this forgotten clinician becomes a meditation on time and a window through which we can perceive the long human history of fate and foresight. It’s also a tale about how we decide what is worthy of science and what it feels like to be left behind. It is a story about a scientific revolution that never happened.

Forty-two years old when the country learned of Aberfan, John Barker was a Cambridge-educated psychiatrist of terrific ambition and rather middling achievement. In his thirties, he had been an unusually young hospital superintendent at a facility in Dorset; a nervous breakdown led to his demotion and reassignment, by the mid-’60s, to Shelton Hospital, where he cared for about 200 of the facility’s thousand patients. Shelton was a Victorian-era asylum in western England, not far from Wales, and a hellish world unto itself. Local doctors called it the “dumping ground,” this 15-acre gothic facility of red-brick buildings hidden behind red-brick walls, where women and men suffering from mental illness were deposited for the rest of their lives. One-third of Shelton’s population had never received a single visitor. Like other mental health facilities in midcentury Britain, it was a place of absolutely crushing neglect. “Nurses smoked constantly,” Knight writes, “in part to block out Shelton’s all-pervading smell: of a house, locked up for years, in which stray animals had occasionally come to piss.” Every week or two, another suicide. “The primary means of discharge was death.”

As a clinician, Barker was tough and demanding. He was also complicated (like all of us) and tough to caricature. Barker had arrived at Shelton as calls for psychiatric reform were growing louder, and he supported efforts to make conditions “as pleasant as possible” for the hospital’s permanent residents, including removing locks from most of the wards and arranging jazz concerts. But he also favored aversion shock therapies and once performed a lobotomy—which, to his credit, he later regretted. At any rate, Barker’s true passion lay elsewhere. As a young medical student, he collected ghost stories from nurses and staff at the London hospital where he was training: sudden and unaccountable cold presences late at night, spectral ward sisters who shouldn’t have been there and who vanished when you looked twice. A “modern doctor” committed to rational methods, his interest in all things paranormal led him to join Britain’s Society for Psychical Research, whose members had been studying unexplained occult phenomena since 1882. Barker had a crystal ball on his desk and spent his weekends at Shelton rambling around haunted houses with his son. He was a man caught between worlds who would eventually fall through the cracks.

The day following the disaster, Barker showed up in Aberfan to interview residents for an ongoing project about people who frightened themselves to death. But he realized quickly that his questioning was insensitive—and as he learned more about the uncanny portents and premonitions that were already swirling around the tragedy, he sensed a much greater opportunity. Barker contacted Peter Fairley, a journalist and science editor at the Evening Standard, with his hunch that some people may have foreseen the disaster through a kind of second sight. Days later, the paper broadcast Barker’s paranormal appeal to its 600,000 subscribers: “Did anyone have a genuine premonition before the coal tip fell on Aberfan? That is what a senior British psychiatrist would like to know.”

A gifted scientific popularizer, Fairley shared with Barker a knack for publicity as well as tremendous ambition. Within weeks, the two men had dramatically expanded the project. From January 1967, readers were told to send general auguries or prophecies to a newly established “Premonitions Bureau” within the newsroom. “We’re asking anyone,” Fairley told a BBC radio interviewer, “who has a dream or a vision or an intensely strong feeling of discomfort” which involves potential danger to themselves or others “to ring us.” With Fairley’s brilliant assistant Jennifer Preston doing most of the work, the team categorized the predictions and tracked their accuracy. Their hope was to prove that precognition was real and convince Parliament to use this psychic power for good by developing a national early warning system for disasters. “Nobody will be scoffed at,” Fairley insisted. “Let us simply get at the truth.”

Seventy-six people wrote to Barker claiming premonitory visions of the Aberfan disaster. Throughout 1967, another 469 psychic warnings were submitted to the Bureau. Many of these submissions came from women and men who claimed to be seers, who experienced precognition throughout their lives as a sort of sixth sense. Kathleen Middleton, the piano teacher who awoke choking before the coal tip collapse, became a regular Bureau contact who had been sensitive to occult forces since she was a girl. (During the Blitz, a vision of disaster convinced her to stay home one night instead of going out with friends; the dance hall was bombed.) Another frequent contributor was Alan Hencher, a telephone operator who wrote that he was “able to foretell certain events” but with “no idea how or why.”

The premonitions gathered by Barker ran the gamut of believability. Some were instantly disqualified. Others were spookily prescient. In early November 1967, both Hencher and Middleton warned of a train derailment; one occurred days later, near London, killing 49 people. Hencher suffered a severe headache on the evening of the disaster and suggested the time of the accident nearly to the minute, before the news had been reported. Most of the premonitions appear to have been vague enough to be right if you wanted them to be, if you were willing to cock your head to one side and squint. A woman reported a dream about a fire; on the day she mailed her letter, a department store in Brussels burned. One day in May 1967, Middleton warned about an impending maritime disaster; an oil tanker ran aground. Visions of airliner crashes inevitably, if one waited long enough, came true somewhere in the world. Barker was determined to believe in them. “Somehow,” he told an interviewer, seers like Hencher and Middleton “can gate-crash the time barrier … see the unleashed wheels of disaster before the rest of us.… They are absolutely genuine. Quite honestly, it staggers me.”Visions of airliner crashes inevitably, if one waited long enough, came true somewhere in the world. Barker was determined to believe in them.

For those of us unable to gate-crash time itself, one wonders what it would be like to have this kind of premonitory sense, to perceive the future so viscerally and so involuntarily. It was like knowing the answer for a test, some explained, with cryptic keywords floating in space in their imaginations. ABERFAN. TRAIN. Others had physiological symptoms. Odd smells, like earth or rotting matter, that nobody else could perceive, or a spasm of tremors and pain at the precise moment when disaster struck far away. People who sensed premonitions explained to Barker that it was an awful burden, that they grappled with, as one put it, “the torment of knowing” and “the problem of deciding whether we should tell what we have received” in the face of potential ridicule or error.

Prone to a certain grandeur, Barker believed that the stakes of the project, which he called “essential material and perhaps the largest study on precognition in existence,” were high. Practically speaking, he thought it would help avert disaster. (If the Premonitions Bureau had been up and running earlier, he boldly claimed, Aberfan could have been avoided and many children’s lives saved.) More daringly, Barker thought that proving the existence of precognition would overturn the basic human understanding of linear time. He wondered if some people were capable of registering “some sort of telepathic ‘shock wave’ induced by a disaster” before it occurred. It might be akin to the psychic bonds felt between twins, but able to vanquish time as well as space. Inspired by Foreknowledge, a book by retired shipping agent and amateur psychic researcher Herbert Saltmarsh, Barker thought that our conscious minds could likely only experience time moving forward, and in three distinct categories: past, present, and future. To our unconscious, however, time might be less stable and more permeable. If scientists would “accept the evidence for precognition from the cases” gathered by the Bureau, he said, they would be “driven to the conclusion that the future does exist here and now—at the present moment.” Barker sensed a career-defining discovery just around the corner.

But it was not to be. John Barker died on August 20, 1968 after a sudden brain aneurysm. He was 44 years old. The Bureau, which Jennifer Preston dutifully continued through the 1970s, and which ultimately included more than 3,000 premonitions, represented the last, unfinished chapter of his brief life. He never wrote his book on precognition and fell into obscurity. The morning before he died, Kathleen Middleton woke up choking.

Knight narrates Barker’s story with considerable generosity and evident care. Rather than condescend or deride him as a crank, Knight thinks with Barker: about the strangeness of time and our human ways of moving through it, about how we make meaning from chaos and resist the truly random, about prediction and cognition and our hunger for prophecy. Yet the many disappointments in Barker’s career were not incidental to his significance, and emphasizing them does not diminish him. In fact, his life can also be framed as a tale told much too rarely in the history of science, about how scientific inquiry relies as much upon failure as success in order to function, on exclusion as much as expansion.

Around the time Barker was appointed to his role at Shelton, the American historian and philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn published a book called The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, a landmark work that now structures practically everyone’s thinking without them realizing it. What Kuhn proposed was that scientific research always occurs within a paradigm: a set of rules and assumptions that reflect not only what we think we know about how the universe works, but also the questions we are permitted to ask about it. At any given moment, “normal science” beavers away within the borders of the current paradigm, working on “legitimate problems” and solving puzzles. For a long while, Kuhn explained, phenomena “that will not fit the box are … not seen at all,” and “fundamental novelties” are suppressed. Eventually, however, there are too many anomalies for which the reigning paradigm cannot account. When a critical mass is reached, the model breaks and a new one is adopted that can better explain things. This is a scientific revolution.

For Barker, precognition constituted what Kuhn would have called a legitimate problem within normal science: It ought to be studied using experimental methods and would, he thought, one day be explained by them. But he admitted the risk that modern psychiatry might not ever be able to accommodate the occult, that his work on premonitions could break the paradigm altogether. Hunches and visions that came true might demand a new way of explaining time and energy. “Existing scientific theories must be transformed or disregarded if they cannot explain all the facts,” he lectured his many critics. “Although unpalatable to many, this attitude is clearly essential to all scientific progress.” He seems to have seen himself as a contemporary Galileo, insisting upon empirical truth in the face of “frivolous and irresponsible” gatekeepers. “What is now unfamiliar,” he argued in the BMJ, usually tends to be “not accepted, even despite overwhelming supportive evidence. Thus for generations the earth was traditionally regarded as flat, and those who opposed this notion were bitterly attacked.” Barker wanted the ruling scientific paradigm to make room for the paranormal—or give way.

It wasn’t so implausible, in midcentury Britain, that it just might. A craze for spiritualism and the paranormal had swept the country between the two world wars, and a rash of new technologies that seemed magical (telegram, radio, television, etc.) left many Britons, not unreasonably, to wonder if “supernatural” phenomena like prophecies or telepathy might turn out to be explainable after all. In Barker’s Britain, one quarter of the population had reported believing in some form of the occult. Even Sigmund Freud, nervously protecting the reputation of psychoanalysis, refused to dismiss paranormal activities “in advance” as being “unscientific, or unworthy, or harmful.” In physics, too, Knight points out, “the old order of time was collapsing” by midcentury, thanks to developments in relativity as well as quantum mechanics. For experts, time had become less predictable and mechanisms of causation less clear, both subatomically and cosmically. Barker had been formed, in other words, by “a society in which one set of certainties had yet to be eclipsed by another.”Premonitions became understood not in terms of extrasensory perception but simply misperception: the work of cognitive error or misfiring neurons rather than the supernatural.

But instead of rearranging itself around Barker’s research into precognition, the paradigm shifted away from him and snapped more firmly into place. The walls sprang up, and the questions that interested Barker became seen as illegitimate and unscientific. The Bureau he built with Fairley was not all that successful. Only about 3 percent of submissions ever came true, and in February 1968 a deadly fire at Shelton Hospital itself went unpredicted, to the unabashed glee of critics and satirists. Barker’s supervisors grew skeptical and then embarrassed. As time went on, and the boundaries of the scientific paradigm in which we still live grew less permeable, occult phenomena were explained not by bending time, but with recourse to cognitive science and neurology. Premonitions became understood not in terms of extrasensory perception but simply misperception: the work of cognitive error or misfiring neurons rather than the supernatural.

The popular understanding of scientific revolutions still revolves around big ruptures and great scientists, the paradigm-defining concepts (like heliocentrism, gravity, or relativity) that transform how human beings think they understand the universe: We shift the frame to move forward. Yet there is just as much to be learned from the times when revolutions don’t occur, when scientific inquiry is defined not by asking thrilling new questions, but by the determination that some old questions will no longer be asked. What’s so brilliant about Knight’s account, in the end, is the way it portrays a creative workaday researcher rather than a modern-day Newton or Einstein, a man aspiring to do normal science while the rules shifted around him; the way it conveys the rarely captured feeling of a paradigm closing in around you and your ideas, until it all fades to black. Ian Beacock @IanPBeacock

Ian Beacock is a frequent contributor to The New Republic. He lives in Vancouver, where he’s working on a book about democratic emotions.Want more on art, books, and culture?Sign up for TNR’s Critical Mass weekly newsletter.ContinueRead More: Critical Mass, Books, Culture, Aberfan, Science, PremonitionsEditor’s Picks

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookies Settings

- Copyright 2022 © The New Republic. All rights reserved.

September 5th 2022

By Melissa Hogenboom23rd August 2022Comments about our looks from our loved ones and friends can cause lifelong insecurities. How can we teach kids to feel confident about their bodies instead?P

Picture the scene: a little girl tries on a sparkly dress, does a twirl and with great satisfaction, smooths it down. The adults around her echo her delight, and tell her how pretty she is. Later she looks at her favourite books, and sees slim people and slender animals going on exciting adventures, while their heavier counterparts are portrayed as slow or clumsy. Sometimes, she notices her own parents fretting about their weight or looks.

By the time she is a teen, her parents may worry how social media influencers are affecting her body image. But research suggests that in reality, her perception of bodies and their social acceptance will have been shaped long before then, in those very early years.

When we think about our relationship with our bodies, it’s often hard to pinpoint precisely where our satisfaction or dissatisfaction comes from. If we cast our minds back to our childhood, however, we may remember a collection of off-hand comments or observations. None of them may seem hugely impactful in themselves. And yet, their cumulative effect can be surprisingly potent.

The writer Glennon Doyle still recalls how her looks as a child earned her praise from the adults around her: “I could see it on their faces… They would light up, and so I learned, this is a currency,” she says on her podcast. But when she grew older and was considered less pretty, that adoration stopped – it was, she says, as if the world had turned away from her.

Whether it comes in the form of compliments or criticism, that kind of attention to body shapes can lay down beliefs and insecurities that are hard to shake off. The consequences can be tremendously damaging, as research shows, with family attitudes and derogatory comments about weight linked to mental health problems and eating disorders. In addition, the broader stigmatisation of overweight children has increased – affecting their self-esteem and of course, body image.

Given how early this awareness of body ideals begin, what can parents and caregivers do to help children feel confident about themselves – and more supportive of others?

From a young age, children are influenced by their parents’ views about physical appearance (Credit: Getty/Javier Hirschfeld)

Family Tree

This article is part of Family Tree, a series that explore the issues and opportunities that families face all over the world. You might also be interested in other stories on childhood and development:

You can also climb new branches of the Family Tree on BBC Worklife and BBC Culture – and check out this playlist on changing families by BBC Reel.

Body shame is taught, not innate

Physical ideals hugely differ across time and different cultures – a quick look at any painting by Peter Paul Rubens, or indeed the 29,500-year-old figurine known as the “Venus of Willendorf“, shows just how exuberantly humans have embraced curvy features. But today, despite a growing body positivity movement that celebrates all shapes and sizes, the idea that a thin body is an ideal one remains dominant on social media, on traditional media, on television, on the big screen and in advertising.

Awareness of body ideals starts early, and reflects children’s experience of the world around them. In one study, children aged three to five were asked to choose a figure from a range of thin to large sizes, to represent a child with positive or negative characteristics. They were for example asked which children would be mean or kind, who would be teased by others and whom they would invite to the birthday. The children tended to choose the bigger figures to represent the negative characteristics.

Crucially, this bias was influenced by others: for example, their own mothers’ attitudes and beliefs about body shapes affected the outcome. Also, the older children displayed a stronger bias than the younger ones, which again indicates that it was learned, not innate. The findings “suggest children’s social environments are important in the development of negative and positive weight attitudes”, the researchers conclude.

“We see the patterns whereby children are attributing the positive characteristics to the thinner figures, and negative characteristics to the larger figures,” says Sian McLean, a psychology lecturer at La Trobe University in Melbourne, Australia, who specialises in body dissatisfaction. “They’re developing that quite early, which is a concern because they potentially have the chance to internalise that perception, that being larger is undesirable and being thinner is desirable and associated with social rewards.”

While parents play an important role in shaping their children’s attitudes and views, it should be emphasised that they are far from the only influence youngsters are exposed to, and can often have a positive effect that can counteract messages from other sources. But the research shows that parents’ views do matter.

Girls as young as five use dieting to control their weight

Another study showed that children as young as three were influenced by their parents’ attitude towards weight. Over time, the children’s negative associations with large bodies, and awareness of how to lose weight, increased. There is often a gender element to these perceptions, with sons more affected by their fathers’ views, and daughters by their mothers’ attitudes. The use of dieting to control weight has even been reported in girls as young as five. Here the main factors were exposure to media, as well as conversations about appearance.

The studies show just how early young children take on the societal perceptions of those around them, paying close attention to how adults behave and talk about bodies and food. That pattern continues, and can even worsen, as they grow older. Research assessing the level of body dissatisfaction and dieting awareness in children aged five to eight found that “the desire for thinness emerges in girls at around age six”. From that age, girls rated their ideal figure as significantly thinner than their current figure. Again, the children’s perception of their mothers’ body dissatisfaction predicted whether the girls then also felt dissatisfied with their own bodies. “A substantial proportion of young children have internalised societal beliefs concerning the ideal body shape and are well aware of dieting as a means for achieving this ideal,” the authors concluded.

Thinking back, most of us will have experienced off-hand comments or observations during our childhood (Credit: Alamy/Javier Hirschfeld)

The danger of teasing

Many parents may feel shocked to hear that their own insecurities – which may after all be completely involuntary, and not something they wish to pass on – can have such an impact. But some family members also magnify this effect through derogatory comments.

In a study on the effects of teasing by family members on body dissatisfaction and eating disorders, 23% of participants reported appearance-related teasing by a parent, and 12% were teased by a parent about being heavy. More reported being teased by their fathers than their mothers. Such paternal teasing was a significant predictor of body dissatisfaction as well as bulimic behaviours and depression, and also increased the odds of being teased by a sibling. Maternal teasing was a significant predictor of depression. Being teased about one’s appearance by a sibling had a similarly negative impact on mental health and self-esteem, and raised the risk of eating disorders.

The authors suggested that understanding a family history of teasing would help health care providers identify those at risk for “body image and eating disturbance and poor psychological functioning”.

I still have a problem eating in front of my mom. She always criticised my eating and weight starting from when I was six. Maybe even before – 49-year-old study participant

Other research on children aged seven to eight has shown that mothers’ comments about weight and body size have been linked to a disordered eating behaviour among their children. Similarly, girls “whose mothers, fathers, and friends encouraged them to lose weight and be lean” were more likely to endorse negative beliefs about others’ weight, known as “fat stereotypes”. This is especially alarming given the rise in weight-related stigmatisation and bullying.

Even adult women can still feel the pain of weight stigma experienced in childhood, a study found, with the participants mainly pointing to their mothers as the source of such stigma. It was “the most hurtful thing I’ve ever experienced“, one participant said. The study quoted women in their 40s, 50s and 60s describing vivid memories of being weight-shamed by their families, and the profound sadness they still felt. “The constant criticism from my mother about my weight led to issues of self-confidence I have struggled with all my life,” one participant reported. “My father and brothers used to hum the ‘baby elephant walk’ tune when I was around eight–11 years old,” said another. “I still have a problem eating in front of my mom,” a 49-year-old participant stated. “She always criticised my eating and weight starting from when I was six. Maybe even before.”

One respondent recalled her mother putting her on a diet at the age of 10: “My feelings of my lack of attractiveness will probably never go away and have been with me all my life even when I was thinner. It is very painful.”

However, some respondents also said they felt their mothers projected their own insecurities, and perhaps intended the comments and advice to be helpful rather than mean.

Some adult women still feel the pain of weight stigma experienced in childhood (Credit: Getty Images/Javier Hirschfeld)

Beyond the family

There’s a reason why parental influence is so strong. Rachel Rodgers, a psychologist at Northeastern University, says that when a parent is concerned with their own body image, they will be modelling behaviours that show “this is important”.

“Even if they’re not mentioning the child’s physical appearance, they’re still acting in a way that suggests to the child, ‘this is something that worries me, this is something that I’m preoccupied with’, and so children pick up on that.”

In addition, many parents do tend to comment on what children are eating, wearing, or how they look, often in a well-meaning way, and that can increase the preoccupation with looks and weight. The resulting “thin idealisation” – a preference for thin bodies – sets children up to believe that their “social worth is contingent on their physical appearance and that’s going to lead them to invest in it in terms of their self-esteem, as well as their time and energy”, says Rodgers.

Of course, parents are not the only source of body stigma, especially as the child grows older. Their peers and the media tend to assume a greater role over time. Even toys such as dolls have an influence. One study featuring girls aged five to nine, found that when they played with an extremely thin doll, it changed their ideal body size to being thinner.

Unless they are countered, these influences can reinforce each other. Many studies show that media exposure contributes to appearance ideals – young girls who watched music videos were more focused on their appearance afterwards, for example. If friends then also talk about weight and appearance, that effect can be magnified.

“The way in which media ideals are supported and endorsed by their peers/friends was a more crucial factor than direct media exposure itself,” explains Jolien Trekels a psychologist studying body image at KU Leuven in Belgium, who led research looking into the role friends play on appearance ideals.

On a positive note, it may mean that young people are not just at the mercy of media ideals, but can collectively shape their own responses to it.

The danger of “thinspiration”

The type of social platform and activity also plays a role. One 2022 review found that Instagram and snapchat (both extremely visual) were more negatively linked to body image than Facebook, while taking and manipulating selfies was more damaging than actually posting them.

Unsurprisingly “thinspiration” content that promotes thinness and dieting, also showed negative effects (due to negative self-comparisons), as did fitness-promoting posts categorised as “fitspiration”.

Although viewing posts about exercise has been shown to increase adult exercise among women, it also internalises thin ideals, according to a 2019 study. This means that this early inspiring effect is not necessarily long lasting, as the study notes: “As time passes and women see no major effects of dieting and exercising, they may become frustrated which may consequently result in body dissatisfaction.”

A negative body image is problematic for many reasons. “Self-worth is often intertwined with one’s bodily self-perceptions,” explains Trekels.

This is especially the case for women and girls. Once a negative body image develops, it is a high predictor for eating disorders and depression. The statistics paint a sobering picture. Estimates suggest that up to half of pre-adolescent girls and teens report body dissatisfaction.

A negative body image in childhood is also likely to persist into adolescence. A recent survey of adults by the charity Butterfly, which offers evidence-based support for eating disorders, found that of those who developed body dissatisfaction early on, 93% said it got worse during adolescence.

Focusing more on a child’s interests rather than how they look could improve a sense of self-satisfaction (Credit: Getty Images/Javier Hirschfeld)

Are girls more at risk?

While girls often seem to be more affected by body image concerns, this may in part be due to the fact that more research exists featuring girls, as well as how consistently the female body is objectified and sexualised early on. Emerging research on boys shows a similar level of dissatisfaction, though their body ideals tend to be a bit different, with a greater focus on wanting to be muscular, for example.

“Really everyone in a body can experience body dissatisfaction, it doesn’t matter what you look like on the outside, it’s how you’re thinking and feeling on the inside,” says Stephanie Damiano, who works at Butterfly.

Trekels has noted similar trends: “Generally, we find more or stronger effects for girls than for boys. However, this does not mean that boys aren’t vulnerable to experiencing these influences, too.”

One reason the effect is stronger for girls could be because, from an early age, girls and boys are socialised differently. Girls are often told that their social value lies in how attractive they are, says Rodgers. “That their bodies are made to be looked at, they are supposed to be contained, docile and not take up too much space,” she says. “Boys are socialised to understand that their bodies are functional, that they’re strong, which is a very different message.”

Given how all-pervasive these messages are, what can parents do to counter them and instead nurture a more generous, positive and empowering body image?

First, as the evidence shows, the way adults talk about bodies around children matters. “We would encourage parents or educators not to make comments about body image, even if they’re positive,” McLean says.

Instead, parents should focus on what the children enjoy doing and are interested in, placing “more value on who they are and their special skills and talents and less focus on what they look like”, says Damiano. This helps children get a sense of satisfaction and self-worth that’s not tied to their appearance. It may also mean working on our own self-perception and self-esteem, given that the research shows how easy it is to transmit our insecurities.

Positive family relationships can help to reduce the negative effects of body dissatisfaction (Credit: Getty Images/Javier Hirschfeld)

Family support makes a difference

Damiano also recommends parents avoid talking about weight or constantly telling children to eat healthier foods. “The more we focus on higher weight as being a problem, or certain foods as being ‘bad’, the more guilt, shame, and body dissatisfaction children are likely to feel.”

Instead, parents can talk about exercise as being important for general health and wellbeing, rather than a way to lose weight. Families can also normalise eating healthy meals, rather than overtly talking about specific foods being bad for you. We all like a treat, after all, so it seems counter-productive to teach children to feel guilty about having one. In fact, enjoying treats is known to be key to a healthy attitude towards weight. Watching TV cooking programmes featuring healthy food, can also subtly encourage children to eat healthier foods.

Family relationships can play an important positive part: one study showed that a good relationship between mothers and their adolescent children can reduce the negative effects of social media use on body dissatisfaction. Limiting children’s time on social media can reduce “appearance comparisons” as well as improve mental health.

“The way that parents provide meaning to what the child is seeing”, is also really important, Rodgers says, as it can help a child decode what the images truly show. And of course, not all social media is bad – it can be a source of community and encouragement, too.

Parents may find it useful to team up with schools. The Butterfly Body Bright programme in Australia helps primary school children develop a positive body image and lifestyle choices. In a pilot programme, the children’s body image was found to improve after one lesson. Intervention programmes that focus on building self-esteem have also shown success. Reflecting on these programmes and their messages may even help parents examine their own ideas around weight and bodies, and cast off long-held, harmful beliefs.

As for what we can do at home, an easy change might be to pause whenever we’re about to praise a child’s appearance, and think of something else we like about them, and want them to know. Instead of telling them “I love your dress”, we could simply smile and tell them how nice it is to see them, and how much fun they are to be around.

* Melissa Hogenboom is the editor of BBC Reel. Her book, The Motherhood Complex, is out now. She is @melissasuzanneh on Twitter.

—

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List” – a handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, Travel and Reel delivered to your inbox every Friday.

By Sophia Smith Galer31st August 2022In the digital age, kids need a trusted source they can turn to with questions about love and sex – and research shows how parents can get it right.I

I never got the opportunity to do something that’s almost a rite of passage among British teens – spend a sex education class peeling a condom out of its stiff foil packet and rolling it down a banana. It wasn’t until I was 27 years old that I would finally get to do it, but in a very different capacity. I wasn’t learning how to put a condom on. I was learning how I’d teach somebody else to put it on.

About 15 newly trained sex educators and I sat in front of our computers, condommed-bananas in hand. “We often use flavoured condoms,” explained our teacher over Zoom, “because the smell is a bit more appealing than normal condoms.” He took a moment to look at the participants’ expressions, and obviously found some of them looking less passive than he’d hoped. “It’s really important that you don’t look or feel squeamish when you do this,” he said. “That’s not how you want young people to feel when you’re encouraging them to use these.”

Many parents may feel a similar sense of squeamishness when trying to talk to their children about physical intimacy – though attitudes to sex education can vary widely between countries and families, research shows.

A review of research on British parents’ involvement in sex education found that they often felt embarrassed, for example, and feared they lacked the skills or the knowledge to talk to their children. However, that same review also found that in countries such as the Netherlands and Sweden, parents talked openly to their children about sex from an early age, and that possibly as a result, teenage pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases were far less common than in England and Wales.

Parents who do feel awkward talking about sex can find themselves in a difficult spot. Many would like their children to know that they can come to them with questions and problems, especially in the digital age, with children coming across graphic online content at an increasingly young age. But they may struggle to decide when and how to start.

Parents may feel squeamish when trying to talk about bodies and intimacy. (Credit: Prashanti Aswani)

Eva Goldfarb, professor of public health at Montclair State University, co-authored a systematic literature review of the past 30 years of comprehensive sex education. While the review focuses on schools, Goldfarb says her research holds important lessons for parents, too. One basic insight is that sex education has a positive, long-term impact, such as helping young people form healthy relationships. Her advice to parents is not to skip or delay these chats.

“Start earlier than you think,” she says. “Even with very young children you can talk about names of body parts and functions, body integrity and control.”

This includes talking about issues that parents may not even think about as sex-related, but that are about relationships more broadly: “Nobody gets what they want all the time, it’s important to treat everyone with kindness and respect.”

In fact, parents tend to find it easier to talk to their children about sex when these conversations start at a young age and come up naturally, separate research suggests. Answering young children’s questions openly and honestly can set a positive pattern that makes it easier to talk about more complex issues later.

This step-by-step approach can also be beneficial for children in terms of understanding their own origins and identity. For example, research has shown that children who were conceived with the help of sperm donation, and whose parents explained this from the start with the help of books and stories, felt more positive about their origins than those who found out later.

For parents who want to broach the subject of sex but don’t quite know how, research has revealed a number of ways to get started.

Many parents would like to be a trusted source for their children, especially in the digital age. (Credit: Prashanti Aswani)

What was your own sex education like?

Over the past few years, I have interviewed dozens of sex educators for my book debunking sex myths and misinformation, Losing It. They are pretty much unanimous when it comes to Lesson One of sex education training – figuring out your own level of sex education before considering passing it on to anybody else.

Numerous studies and surveys suggest that adults often do not know as much about sex and the body as they would like to, and may even have completely inaccurate ideas that are grounded in myth or guesswork. For example, many people around the world erroneously believe that the state of a woman’s hymen can prove whether she is a virgin – an idea that has no scientific basis.

Parents’ basic level of knowledge can vary widely. Some may identify with the subjects of a study in Namibia, which found that many parents didn’t talk to their children about sex because they themselves felt that their knowledge about human sexuality, or their ability to explain it, was inadequate. But a survey of almost 2,000 parents of young children in China found that parents’ own sexual knowledge and sex education was generally good, though they were less knowledgeable when it came to issues around child development, which made it difficult for them to be effective educators.

Some of the Namibian respondents also avoided the topic because they viewed sex as taboo, or they thought discussing it was going to encourage young people to have sex. The idea that talking to children about sex will encourage them to think about things that aren’t age appropriate, or seek out sexual experiences, remains common around the world, including in the US. It tends to be linked to the belief that teaching abstinence from sex until marriage is the best way to protect young people’s health and safety.

However, research has shown the opposite. Simply telling teenagers not to have sex has been conclusively proven not to work. The American Academy of Pediatrics calls educational programmes that only promote abstinence “ineffective”, based on a systematic review of the evidence. The review also shows that comprehensive sex education helps prevent and reduce the risks of teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases, echoing the findings in the Netherlands and Sweden.

When parents delay or skip the topic of sex, young people can be left vulnerable to misinformation (Credit: Prashanti Aswani)