April 17th 2024

The Paradox That’s Supercharging Climate Change

Humanity needs to burn less fossil fuels. But that means fewer aerosols to help cool the planet—and a potential acceleration of global warming.

No good deed goes unpunished—and that includes trying to slow climate change. By cutting greenhouse gas emissions, humanity will spew out fewer planet-cooling aerosols—small particles of pollution that act like tiny umbrellas to bounce some of the sun’s energy back into space.

“Even more important than this direct reflection effect, they alter the properties of clouds,” says Øivind Hodnebrog, a climate researcher at the Center for International Climate Research in Oslo, Norway. “In essence, they make the clouds brighter, and the clouds reflect sunlight back into space.”

So as governments better regulate air quality and deploy renewable energy and electric vehicles, we’ll get less warming thanks to fewer insulating emissions going into the sky, but some additional warming because we’ve lost some reflective pollution. Hodnebrog’s new research suggests that this aerosol effect has already contributed to a significant amount of heating.

The most important component in fossil fuel pollution is gaseous sulfur dioxide, which forms aerosols in the atmosphere that linger for mere days. So slashing pollution has an almost immediate effect, unlike with carbon dioxide, which lasts for centuries in the atmosphere.

It’s a gnarly, unavoidable catch-22, but in no way a reason to keep polluting willy-nilly. Fossil fuel aerosols kill millions of people a year by contributing to respiratory problems, cardiovascular diseases, and other health issues. So by decarbonizing we’ll improve both planetary and human health. The urgency is growing by the day: Last year was by far the hottest on record, and this March was the 10th month in a row to notch all-time highs. Meanwhile, ocean temperatures—boosted by El Niño, the warm band of water that periodically arises in the Pacific, which also added heat to the atmosphere—have soared to and maintained record highs for over a year, stunning scientists.

“The preponderance of those records and the margins by which they were broken was eye-opening,” says Jennifer Francis, senior scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center in Massachusetts. “Until society manages to stop increasing the greenhouse blanket, record-smashing events like those in 2023 will become more common, even without the boost from El Niño.”

Slowing down the growth of that insulating blanket is already underway. “We seem to be flattening greenhouse gas emissions, which is a good thing,” says Zeke Hausfather, a research scientist at Berkeley Earth. “But we’re also uncovering some warming that our pollution had historically been masking. And because of that, our models expected—and we seem to be starting to see—some evidence of a speed-up in the rate of surface warming.” This is known in climate science as acceleration. Hausfather points to data showing that since 1970, the warming rate was 0.18 degree Celsius per decade, which has jumped to about 0.3 degree Celsius per decade over the past 15 years.

In his new paper, published in the journal Communications Earth and Environment, Hodnebrog and his colleagues set out to quantify just how much an effect curbing aerosols has had. To start, they gathered measurements between 2001 and 2019 from the Clouds and the Earth’s Radiant Energy System, satellite instruments that detect the difference in the solar energy coming to our planet and the energy reflected back out into space. This is the overall “energy imbalance” of the Earth, with it trending upwards as the world warms.

Featured VideoClimate Scientist Answers Earth Questions From Twitter

Most Popular

- BusinessAirchat Is Silicon Valley’s Latest ObsessionLauren Goode

- PoliticsDonald Trump Poses a Unique Threat to Truth Social, Says Truth SocialWilliam Turton

- GearIkea’s New Range Is Stealth Mode for GamersEric Ravenscraft

- PoliticsFake Footage of Iran’s Attack on Israel Is Going ViralVittoria Elliott

The researchers then fed global emissions data into four different state-of-the-art climate models and managed to reproduce those satellite measurements. “When we set the aerosol emissions to constant—so we didn’t include any change over time in the aerosol emissions—then this upward trend in the energy imbalance was much reduced, and we didn’t manage to reproduce the satellite measurements,” says Hodnebrog. “So our main conclusion is that these aerosol emission reductions need to be accounted for in order to explain what we see now, what we measure from space.”

The researchers found that over the past two decades, the reduction in aerosol emissions has accounted for nearly 40 percent of the increase in energy imbalance—that is, the extra warming energy that’s raised global temperatures. “I would be surprised if this will not lead to temporary acceleration in surface temperature warming,” says Hodnebrog of the ongoing tailing off of aerosol emissions.

Projecting forward with aerosols, though, is tricky, because we’re dealing with extraordinarily complex atmospheric processes. For one, modeling cloud formation is notoriously difficult, and it’s hard to tell just how much human-made aerosols contribute to a given cloud versus natural aerosols.

There’s also uncertainty about how strong a cooling effect aerosols have up in the sky. If they have an intense cooling effect, we’ll get more warming in the future as they decrease. It’d be like switching off the planet’s air conditioning. But if they have a milder cooling effect, losing them wouldn’t lead to as much warming. In 2022, a separate team of scientists calculated that if it ends up being the latter case, we’d have a better chance of keeping warming below the 1.5-degree Celsius limit established in the Paris Agreement. (In their new aerosols paper, Hodnebrog and his colleagues accounted for this uncertainty by running those different models, which had different representations of aerosols and their interactions with clouds. Their results were the average of the four models.)

Even in the present day, some scientists are skeptical that we’re seeing acceleration of global warming from reduced aerosols. “Yes, it is responsible for the acceleration in warming during the 1970s to 1980s,” says climate scientist Michael Mann of the University of Pennsylvania. That was when clean-air regulations started requiring “scrubbers” on coal-fired power plants to remove the sulfur dioxide that forms aerosols. “There is no evidence for any acceleration over the past few decades, however.”

Instead, we could be seeing natural variability, Mann says—the rising and falling of global temperatures over the years that Earth would see even in the absence of human-caused warming. Last year was a good illustration of this. Record-smashing temperatures were due to humans failing to stop pumping so much carbon into the atmosphere, but also due in part to the natural emergence of El Niño. “Think of it as a tide on top of a rising sea,” Mann says. “The rising sea—the steady warming—is what we should be concerned about, and that will continue until net emissions reach zero.”

That much is very clear, and very much agreed upon by scientists: Humans need to stop burning fossil fuels, even if losing some aerosols leads to additional warming going forward. “Right now the recent acceleration is borderline significant, which is why there’s some debate,” says Francis. “But aside from all this, the real story is the relentless global warming that we know is caused by the thickening blanket of greenhouse gases owing to human activities.”

April 9th 2024

Why is it raining so much?

Ben Rich

BBC Weather

- Published5 hours ago

It’s been really wet recently – but just how wet and why?

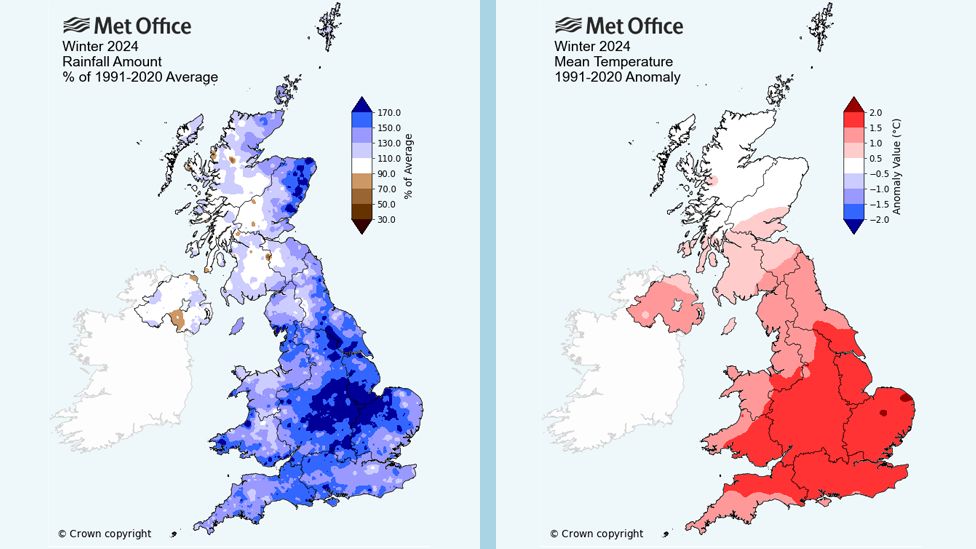

We had the eighth wettest winter since records began more than 150 years ago. The start of spring continued that theme with England and Wales having more than one and a half times their average March rainfall.

As well as being wet it has been mild. And globally it was the warmest March on record, the tenth record-breaking month in a row.

So what part does climate change play in our washout weather?

Warmer means wetter

Wetter weather will be a feature of our changing climate in the UK.

The Met Office predicts that by 2070, winters in the UK will be up to 30% wetter than they were in 1990 and that rainfall will be up to 25% more intense.

Summers will actually get drier overall – with more heatwaves and droughts – but when rain does come it will be heavier, 20% more intense than it was in 1990.

The most violent downpours – more than 30mm of rain in an hour – are expected to occur twice as often as they used to.

This means the increased risk of flooding – with ground becoming saturated by persistent winter rainfall and drainage systems overwhelmed by summer deluges.

Why more rain?

The simple answer is that warm air is able to hold more moisture.

For every degree of warming the amount of water vapour in the atmosphere increases by around 7% fuelling more intense rainfall.

Overall the earth’s climate has already warmed by more than 1°C since pre-industrial times, and recent months have been even warmer than that. For as long as this warming trend goes on the atmosphere’s capacity to hold water vapour will continue to increase.

This doesn’t mean it will get wetter everywhere though. Climate change is also altering wind patterns meaning that some areas such as parts of southern Africa and the Amazon are becoming drier and hotter.

Read More https://www.bbc.co.uk/weather/articles/c3gqxrnd5keo

Comment

Obviously mainstream media is not going to mention effects of Ukraine, Gaza and all the other wars. Nor will they mention overpopulation and air travel.

R J Cook

April 3rd 2024

A man was caught up in the Taiwan earthquake whilst swimming in a hotel rooftop pool in Taiwan’s capital city, Taipei.

The magnitude 7.4 earthquake caused widespread destruction and at least nine people have been confirmed dead.

The earthquake is the strongest recorded in Taiwan in 25 years.

- SubsectionAsia

Explore more

- Watch moment magnitude 7.4 earthquake hits Taiwan. Video, 00:01:24Watch moment magnitude 7.4 earthquake hits Taiwan

- SubsectionAsia

- Published8 hours ago

1:24

- SubsectionAsia

- Published6 hours ago

Up Next

1:24

- SubsectionAsia

- Published1 September 2023

0:17

- SubsectionAsia

- Published19 September 2022

0:43

March 30th 2024

The Surprising Downsides to Planting Trillions of Trees

Large tree-planting initiatives often fail — and some have even fueled deforestation. There’s a better way.

- Benji Jones

Read when you’ve got time to spare.

Advertisement

More from Vox

- What Lula’s stunning victory means for the imperiled Amazon rainforest

- Billionaires like Jeff Bezos are throwing money at biodiversity. Will it work?

- The Earth Is Getting Greener. Hurray?

Advertisement

Photo by Asim Hafeez/Bloomberg via Getty Images

On November 11, 2019, volunteers planted 11 million trees in Turkey as part of a government-backed initiative called Breath for the Future. In one northern city, the tree-planting campaign set the Guinness World Record for the most saplings planted in one hour in a single location: 303,150.

“By planting millions of young trees, the nation is working to foster a new, lush green Turkey,” Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, said when he kicked off the project inAnkara.

Less than three months later, up to 90 percent of the saplings were dead, the Guardian reported. The trees were planted at the wrong time and there wasn’t enough rainfall to support the saplings, the head of the country’s agriculture and forestry trade union told the paper.

Seedlings of the peroba rosa tree at a nursery in Aimorés, Brazil. Christian Ender/Getty Images

In the past few decades, mass tree-planting campaigns like this one have gained popularity as a salve for many of our modern woes, from climate change to the extinction crisis. Companies and billionaires love these kinds of initiatives. So do politicians. Really, what’s not to like about trees? They suck up carbon emissions naturally while providing resources for wildlife and humans — and they’re even nice to look at. It sounds like a win-win-win.

There’s just one problem: These campaigns often don’t work, and sometimes they can even fuel deforestation.

In one study in the journal Nature, for example, researchers examined long-term restoration efforts in northern India, a country that has invested huge amounts of money into planting over the last 50 years. The authors found “no evidence” that planting offered substantial climate benefits orsupported the livelihoods of local communities.

The study is among the most comprehensive analyses of restoration projects to date, but it’s just one example in a litany of failed campaigns that call into question the value of big tree-planting initiatives. Often, the allure of bold targets obscures the challenges involved in seeing them through, and the underlying forces that destroy ecosystems in the first place.

Instead of focusing on planting huge numbers of trees, experts told Vox, we should focus on growingtrees for the long haul, protecting and restoring ecosystems beyond just forests, and empowering the local communities that are best positioned to care for them.

A tree nursery in Karachi, Pakistan. Asim Hafeez/Bloomberg via Getty Images

The push to plant a trillion trees

Since the 1990s, the number of tree-planting organizations has skyrocketed, growing nearly threefold in the tropics alone. So have global drives: Today, there are no fewer than three campaigns focused on planting 1 trillion trees, including the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) One Trillion Trees Initiative, which launched in 2020.

It is hard to identify the exact moment when we became obsessed with planting trees. Some scientists point to the 2011 Bonn Challenge, which set an initial goal of restoring 150 million hectares of degraded and deforested land globally by 2020 and 350 million hectares by 2030. Others highlight a highly controversial study that appeared in Science in 2019 and inspired the WEF’s trillion tree campaign.

The authors of the Science paper originally argued that restoring trees is “our most effective climate change solution to date” and said there’s “room” for 900 million hectares (2.2 billion acres) of new trees across the world. Almost 600 media outlets (including Vox) ran stories about the study in 2019, according to Carbon Brief.

While many scientists criticized the paper, the idea behind it — that we can plant our way out of climate change, while simultaneously solving other problems like biodiversity loss — has stuck around. It’s a charming notion that’s much easier for companies or countries to act on, compared with doing the hard work of slashing greenhouse emissions.

A view from above a tree nursery in Aimorés, Brazil. Christian Ender/Getty Images

Many tree-planting projects fail

Tree-planting campaigns are typically well-intentioned, but they often fall short ofdelivering the benefits they promise, from capturing carbon to providing refuge for rare species. “Large-scale tree planting programs have high failure rates,” theauthors of one paper, led by environmental researcher Forrest Fleischman, wrote in 2020.

One of the most stunning examples of these failures comes from Fleischman’s research in northern India. If there’s a place where tree-planting projects might work, it’s in the state of Himachal Pradesh, said Fleischman, an associate professor at the University of Minnesota who led the Nature study. The state government has a strong track record of delivering services to the public, he said, and has been planting trees since at least 1980.

An analysis of satellite imagery and interviews with hundreds of households, however, revealed that decades of planting by the government — amounting to hundreds of millions of seedlings — “had almost no impact on forest canopy cover,” Fleischman wrote on Twitter. The researchers also measured a shift in the type of trees within the ecosystem, away from species that locals prefer for firewood and animal fodder. In other words, residents of Himachal Pradesh actually had fewer useful forest resources.

What went wrong? Some of the trees may have died quickly because they were planted in poor-quality habitat, Fleischman suspects. Farm animals could have also destroyed the saplings if they were planted in former grazing lands, he said. “Well-resourced forest restoration programs can fail to achieve their goals,” he added. “We need to be more skeptical of big claims.”

In other parts of the world, tree-planting projects didn’t just fail, butalso harmed existing ecosystems or ways of life.

In Mexico, a $3.4 billion tree-planting campaign launched by the government in 2018 actually caused deforestation, as Bloomberg News’ Max de Haldevang reported earlier this year. The program known as Sembrando Vida, or Sowing Life, pays farmers to plant trees on their land, but in some cases, they would clear a chunk of forest before putting seedlings in the ground. One analysis by the World Resources Institute, an environmental group, suggests that it caused almost 73,000 hectares of forest lossin 2019.

In Pakistan, researchers have linked a large, government-backed planting campaign that began in 2014 — known then as the Billion Tree Tsunami — to the erosion of culture and livelihoods of a nomadic group called the Gujjars. Traditionally, Gujjars rent winter pastures from landowners in parts of Pakistan to graze their animals. But through the tree-planting campaign, many of those landowners have replaced grazing land with tree plantations. “Many of the Gujjars have lost access to the private land on which they used to graze their animals in the winter,” Usman Ashraf, a researcher at the University of Helsinki, wrote in a 2018 paper.

Researchers have also blamed large tree-planting efforts in China and Brazil for degrading grassland ecosystems. As I’ve previously reported, grasslands store vast amounts of carbon — most of which is below ground — and provide homes for countless species. Yet these ecosystems are sometimes considered degraded and aretargeted for forest restoration campaigns.

“We need to be looking at all of our ecosystems and not just put trees everywhere,” said Karen Holl, a professor of environmental studies and restoration expert at the University of California Santa Cruz.

How to restore forests for the long haul

Solving a problem as vast as climate change or biodiversity loss is never as straightforwardas planting lots of trees. People often think, “We’ll just plant trees and call that a restoration project, and we’ll exonerate our carbon sins,” said Robin Chazdon, a forest researcher at the University of the Sunshine Coast. Usually, she said, “that fails.”

Buzzy tree-planting programs tend to obscure the fact that restoration requires a long-term commitment of resources and many years of monitoring. “We should just stop thinking about only tree-planting,” as climate scientist Lalisa Duguma has said. “It has to be tree-growing.” Even fast-growing trees take at least three years to mature, he added, while others can require eight years or more. “If our thinking of growing trees is downgraded to planting trees, we miss that big part of the investment that is required,” Duguma said.

Volunteers plant trees in southern China’s Hainan Province. Xinhua/Yang Guanyu via Getty Images

Holl, who has been involved in reviewing projects under the World Economic Forum’s trillion trees program, said she was “shocked” that many proposals called for two years or less of monitoring. “That’s not how long it takes for us to get the carbon or the biodiversity benefits that we want,” she said. (Companies with planting projects under the WEF program must report on progress each year for the duration of their projects, which the companies determine, a WEF spokesperson told Vox. Those reports typically include information on the projects’ social and ecological benefits, the spokesperson said.)

A bigger problem still is that many large planting campaigns don’t account for the underlying social or economic conditions that fuel deforestation in the first place. People may cut down trees to collect firewood or carve out land for their animals. In those cases, putting seedlings in the ground won’t do much to end deforestation. “Planting trees might not be the intervention,” Fleischman said. “The intervention might be giving people a substitute for firewood.”

This problem played out in Brazil after the 2019 fires in the Amazon rainforest. The group of powerful countries known as the G7 responded by offering to pay for restoration — but this offer didn’t address “the core issues of enforcing laws, protecting lands of indigenous people, and providing incentives to landowners to maintain forest cover,” Holl and her co-author wrote in a perspective in Science. The following year, Amazon fires and deforestation both surged. “The simplistic assumption that tree planting can immediately compensate for clearing intact forest is not uncommon,” they wrote.

Ultimately, the only true global solution to restoring ecosystems is to support Indigenous and rural communities, Fleischman said. “Let’s look at places and think about how we can improve people’s lives,” he said. “The people who need nature are going to vote for nature.”

When planting trees works

To be clear, there are plenty of successful restoration programs — and they’re getting better, said Chazdon, who’s also an adviser for the WEF trillion trees campaign. “There is ample evidence that when restoration is done properly, it works,” she said.

Consider the Pontal do Paranapanema, a region in southern Brazil home to vulnerable species like the rare black lion tamarin monkey. Over the last 35 years, a nonprofit called Instituto de Pesquisas Ecológicas has worked with local communities to plant some 2.7 million native trees, as Mongabay’s Liz Kimbrough reports. The trees provide useful products that locals want, such as fruit to eat and wood for building, and a new revenue stream from selling seedlings. At the same time, the new trees create a network of forest corridors that has helped populations of the tamarin recover. In this case, it really does seem to be a win-win-win.

At the center of successful tree-planting campaigns like this are people, said Chazdon, who is compiling examples of effective restoration projects for a new mapping platform called Restor. As it happens, the platform is led by Thomas Crowther, an author of the controversial 2019study in Science, which helped fuel the forest restoration frenzy.

Even Crowther acknowledges that headlines stemming from the paper — namely, that we should plant a trillion trees — were too simplistic and even misleading. “We messed up the communications so badly,” Crowther told the Guardian earlier this month. “I hate that people keep asking me: where are you going to plant these trillion trees? I’ve never in my life said we should plant a trillion trees.” Crowther and his co-authors even revised the abstract of the Science paper to clarify their claim that tree restoration is “one of” themost effective solutions to fight climate change — not the most important one.

Forests are, of course, good for the planet. And they doabsorb loads of greenhouse gases, making them an important bulwark against rising temperatures. But headline-grabbing campaigns focused solely on planting trees can harm both people and ecosystems by focusing more on the goal itself than on the purpose behind it — and distracting us from the hard work of reducing emissions. The tough reality, as Holl puts it, is that “we’re not going to plant our way out of climate change.”

March 21st 2024

Why Is the Sea So Hot?

A startling rise in sea-surface temperatures suggests that we may not understand how fast the climate is changing.

March 15, 2024

In early 2023, climate scientists—and anyone else paying attention to the data—started to notice something strange. At the beginning of March, sea-surface temperatures began to rise. By April, they’d set a new record: the average temperature at the surface of the world’s oceans, excluding those at the poles, was just a shade under seventy degrees. Typically, the highest sea-surface temperatures of the year are observed in March, toward the end of the Southern Hemisphere’s summer. Last year, temperatures remained abnormally high through the Southern Hemisphere’s autumn and beyond, breaking the monthly records for May, June, July, and other months. The North Atlantic was particularly bathtub-like; in the words of Copernicus, an arm of the European Union’s space service, temperatures in the basin were “off the charts.”

Since the start of 2024, sea-surface temperatures have continued to climb; in February, they set yet another record. In a warming world, ocean temperatures are expected to rise and keep on rising. But, for the last twelve months, the seas have been so feverish that scientists are starting to worry about not just the physical impacts of all that heat but the theoretical implications. Can the past year be explained by what’s already known about climate change, or are there forces at work that haven’t been accounted for? And, if it’s the latter, does this mean that projections of warming, already decidedly grim, are underestimating the dangers?

Daily

Our flagship newsletter highlights the best of The New Yorker, including top stories, fiction, humor, and podcasts.

E-mail address

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

“We don’t really know what’s going on,” Gavin Schmidt, the director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, told me. “And we haven’t really known what’s going on since about March of last year.” He called the situation “disquieting.”

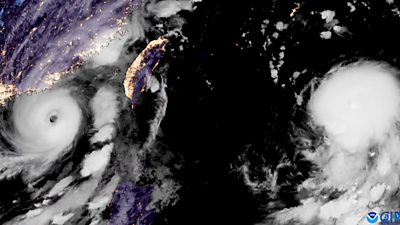

Last winter, before ocean temperatures began their record run, the world was in the cool—or La Niña—phase of a climate pattern that goes by the acronym ENSO. By summer, an El Niño—or warm phase—had begun. Since ocean temperatures started to climb before the start of El Niño, the shift, by itself, seems insufficient to account for what’s going on. Meanwhile, the margin by which records are being shattered exceeds what’s usually seen during El Niños.

“It’s not like we’re breaking records by a little bit now and then,” Brian McNoldy, a hurricane researcher at the University of Miami, said. “It’s like the whole climate just fast-forwarded by fifty or a hundred years. That’s how strange this looks.” It’s estimated that in 2023 the heat content in the upper two thousand metres of the oceans increased by at least nine zettajoules. For comparison’s sake, the world’s annual energy consumption amounts to about 0.6 zettajoules.

A variety of circumstances and events have been cited as possible contributors to the past year’s anomalous warmth. One is the January, 2022, eruption of an underwater volcano in the South Pacific called Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha‘apai. Usually, volcanoes emit sulfur dioxide, which produces a temporary cooling effect, and water vapor, which does the opposite. Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha‘apai produced relatively little sulfur dioxide but a fantastic amount of water vapor, and its warming effects, it’s believed, are still being felt.

Video From The New YorkerHow Ava DuVernay Restages History in “Origin”

Another factor is the current solar cycle, known as Solar Cycle 25. Solar activity is ramping up—it’s expected to peak this year or next—and this, too, may be producing an extra bit of warming.

Yet another is a change in the composition of shipping fuel. Regulations that went into effect in 2020 reduced the amount of sulfur in the fuel used by supertankers. This reduction, in turn, has led to a decline in a type of air pollution that, through direct and indirect effects, reflects sunlight back to space. It’s thought that this change has led to an increase in the amount of energy being absorbed by the seas, though quantifying the effect is difficult.

Can all of these factors together account for what’s going on? Climate scientists say it’s possible. There’s also a lot of noise in the climate system. “This could end up just being natural variability,” Susan Wijffels, a senior scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, said.

But, possibly, something else is going on—something that scientists haven’t yet accounted for. This spring, ENSO is expected to transition into what scientists call “neutral” conditions. If precedent holds, then when this occurs ocean temperatures should start to run more in line with long-term trends.

“I think the real test will be what happens in the next twelve months,” Wijffels said. “If temperatures remain very high, then I would say more people in the community will be really alarmed and say ‘O.K., this is outside of what we can explain.’ ”

In 2023, which was by far the warmest year on record on land, as well as in the oceans, many countries experienced record-breaking heat waves or record-breaking wildfires or record-breaking rainstorms or some combination of these. (Last year, in the United States, there were twenty-eight weather-related disasters that caused more than a billion dollars’ worth of damage—another record.) If the climate projections are accurate, then the year was a preview of things to come, which is scary enough. But, if the projections are missing something, that’s potentially even more terrifying, though scientists tend to use more measured terms.

“The other thing that this could all be is, we are starting to see shifts in how the system responds,” Schmidt observed. “All of these statistics that we’re talking about, they’re taken from the prior data. But nothing in the prior data looked like 2023. Does that mean that the prior data are no longer predictive because the system has changed? I can’t rule that out, and that would obviously be very concerning.” ♦

January 5th 2024

How crowded are the oceans? New maps show what flew under the radar until now

/

Advances in AI and satellite imagery allowed researchers to create the clearest picture yet of human activity at sea, revealing clandestine fishing activity and a boom in offshore energy development.

By Justine Calma, a senior science reporter covering climate change, clean energy, and environmental justice with more than a decade of experience. She is also the host of Hell or High Water: When Disaster Hits Home, a podcast from Vox Media and Audible Originals.

Jan 3, 2024, 4:00 PM GMT|

Share this story

:no_upscale():format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25200824/image_1.gif)

Using satellite imagery and AI, researchers have mapped human activity at sea with more precision than ever before. The effort exposed a huge amount of industrial activity that previously flew under the radar, from suspicious fishing operations to an explosion of offshore energy development.

The maps were published today in the journal Nature. The research led by Google-backed nonprofit Global Fishing Watch revealed that a whopping three-quarters of the world’s industrial fishing vessels are not publicly tracked. Up to 30 percent of transport and energy vessels also escape public tracking.

Those blind spots could hamper global conservation efforts, the researchers say. To better protect the world’s oceans and fisheries, policymakers need a more accurate picture of where people are exploiting resources at sea.

“The question is which 30 percent should we protect?”

Nearly every nation on Earth has agreed to a joint goal of protecting 30 percent of Earth’s land and waters by 2030 under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework adopted last year. “The question is which 30 percent should we protect? And you can’t have discussions about where the fishing activity, where the oil platforms are unless you have this map,” says David Kroodsma, one of the authors of the Nature paper and director of research and innovation at Global Fishing Watch.

Until now, Global Fishing Watch and other organizations relied primarily on the maritime Automatic Identification System (AIS) to see what was happening at sea. The system tracks vessels that carry a box that sends out radio signals, and the data has been used in the past to document overfishing and forced labor on vessels. Even so, there are major limitations with the system. Requirements to carry AIS vary by country and vessel type. And it’s pretty easy for someone to turn the box off when they want to avoid detection, or cruise through locations where signal strength is spotty.

To fill in the blanks, Kroodsma and his colleagues analyzed 2,000 terabytes of imagery from the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-1 satellite constellation. Instead of taking traditional optical imagery, which is like snapping photos with a camera, Sentinel-1 uses advanced radar instruments to observe the surface of the Earth. Radar can penetrate clouds and “see” in the dark — and it was able to spot offshore activity that AIS missed.

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25200814/image_3.png)

Data analysis reveals that about 75 percent of the world’s industrial fishing vessels are not publicly tracked, with much of that fishing taking place around Africa and South Asia.Image: Global Fishing Watch

Since 2,000 terabytes is an enormous amount of data to crunch, the researchers developed three deep-learning models to classify each detected vessel, estimate their size, and sort out different kinds of offshore infrastructure. They monitored some 15 percent of the world’s oceans where 75 percent of industrial activity takes place, paying attention to both vessel movements and the development of stationary offshore structures like oil rigs and wind turbines between 2017 and 2021.

While fishing activity dipped at the onset of the covid-19 pandemic in 2020, they found dense vessel traffic in areas that “previously showed little to no vessel activity” in public tracking systems — particularly around South and Southeast Asia, and the northern and western coasts of Africa.

A boom in offshore energy development was also visible in the data. Wind turbines outnumbered oil structures by the end of 2020. Turbines made up 48 percent of all ocean infrastructure by the following year, while oil structures accounted for 38 percent.

Nearly all of the offshore wind development took place off the coasts of northern Europe and China. In the Northeast US, clean energy opponents have tried to falsely link whale deaths to upcoming offshore wind development even though evidence points to vessel strikes being the problem.

Oil structures have a lot more vessels swarming around them than wind turbines. Tank vessels are used at times to transport oil to shore as an alternative to pipelines. The number of oil structures grew 16 percent over the five years studied. And offshore oil development was linked to five times as much vessel traffic globally as wind turbines in 2021. “The actual amount of vessel traffic globally from wind turbines is tiny, compared to the rest of traffic,” Kroodsma says.

:no_upscale():format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25200832/image_2.gif)

Two thousand terabytes of satellite imagery were analyzed to detect offshore infrastructure in coastal waters across six continents where more than three-quarters of industrial activity is concentrated.Image: Global Fishing Watch

When asked whether this type of study would have been possible without artificial intelligence, “The short answer is no, I don’t think so,” says Fernando Paolo, lead author of the study and machine learning engineer at Global Fishing Watch.“Deep learning excels at finding patterns in large amounts of data.”

New machine learning tools being developed as open-source software to process global satellite imagery “democratize access to data and tools and allow researchers, analysts and policymakers in low-income countries to leverage tracking technologies at low cost,” says another article published in Nature today that comments on Paolo and Kroodsma’s research. “Until now, no comprehensive, global map of these different types of maritime infrastructure had been available,” says the article written by Microsoft postdoctoral researcher Konstantin Klemmer and University of Colorado Boulder assistant professor Esther Rolf.

The technological advances come at a crucial time for documenting fast-moving changes in maritime activity, while nations try to stop climate change and protect biodiversity before its too late. “The reason this matters is because it’s getting more crowded [at sea] and it’s getting more used and suddenly you have to decide how we’re going to manage this giant global commons,” Kroodsma tells The Verge. “It can’t be the Wild West. And that’s the way it’s been historically.”

https://volume.vox-cdn.com/embed/fefb1259f?autoplay=false&loop=true&placement=article&player_type=youtube&tracking=article:middleWho owns the boats looting the high seas?

Most Popular

- How crowded are the oceans? New maps show what flew under the radar until now

- Clicks is a BlackBerry-style iPhone keyboard case designed for creators

- Amazon’s note-taking Kindle Scribe has fallen to one of its best prices to date

- Microsoft’s new Copilot key is the first big change to Windows keyboards in 30 years

- Tesla lowers Model Y, S, and X range estimations following exaggeration complaints

Verge Deals

/ Sign up for Verge Deals to get deals on products we’ve tested sent to your inbox daily.Email (required)

By submitting your email, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Notice. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

More from Science

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24090206/STK171_VRG_Illo_3_Normand_ElonMusk_03.jpg) SpaceX accused of illegally firing employees who criticized Elon Musk

SpaceX accused of illegally firing employees who criticized Elon Musk:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25201200/20231220_PA012_Winter_Promo_Personal_Cup_Launch_Stills_FY24_Q1_050.jpg) Starbucks customers can drive up to the window with their reusable cups now

Starbucks customers can drive up to the window with their reusable cups now:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23935558/acastro_STK103__01.jpg) Hey Alexa, quit it with the bootleg Viagra, says the FDA

Hey Alexa, quit it with the bootleg Viagra, says the FDA:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25190319/954304174.jpg) Amazon plans to make its own hydrogen to power vehicles

Amazon plans to make its own hydrogen to power vehicles

October 8th 2023

Rosebank Oil Field Was Just Approved. Here’s Why It’s A Big Deal

27/09/2023 02:03pm BST

Developers just got the green light to work on the divisive oil field known as Rosebank – prompting major environmental concerns.

Here’s what you need to know, and why this new decision is so controversial.

What is Rosebank?

Rosebank is 80 miles west from Shetland and the UK’s largest untapped oil field with an estimated 300 million barrels of the fossil fuel inside.

At its peak, it could produce 69,000 barrels of oil a day, and harvest 44 million cubic feet of gas per day in its first 10 years.

The oil and gas regulator, the North Sea Transition Authority, said that this development would be in “accordance with our published guidance and taking net zero considerations into account throughout the project’s lifecycle”.

Rosebank’s owners, Norwegian state energy company Equinor and British oil and gas company Ithaca Energy, say that if production begins in 2026, the “largest undeveloped field in the UK” could make up 8% of the UK’s total oil production over the following four years.

The executive chair of Ithaca Energy, Gilad Myerson, also told Times Radio on Wednesday that the decision “makes a lot of sense”, because the UK is likely to relay on fossil fuels for decades to come.

August 26th 2023

This Bold Plan to Kick the World’s Coal Habit Might Actually Work

Novel climate-financing deals are promising to shut off dirty energy plants in developing countries and retrain their staff to work in the green economy.

One hundred miles east of Johannesburg in South Africa, the Komati Power Station is hard to miss, looming above the flat grassland and farming landscapes like an enormous eruption of concrete, brick, and metal.

When the coal-fired power station first spun up its turbines in 1961, it had twice the capacity of any existing power station in South Africa. It has been operational for more than half a century, but as of October 2022, Komati has been retired—the stacks are cold and the coal deliveries have stopped.

Now a different kind of activity is taking place on the site, transforming it into a beacon of clean energy: 150 MW of solar, 70 MW of wind, and 150 MW of storage batteries. The beating of coal-fired swords into sustainable plowshares has become the new narrative for the Mpumalanga province, home to most of South Africa’s coal-fired power stations, including Komati.

To get here, the South African government has had to think outside the box. Phasing out South Africa’s aging coal-fired power station fleet—which supplies 86 percent of the country’s electricity—is expensive and politically risky, and could come at enormous social and economic cost to a nation already struggling with energy security and socioeconomic inequality. In the past, bits and pieces of energy-transition funding have come in from organizations such as the World Bank, which assisted with the Komati repurposing, but for South Africa to truly leave coal behind, something financially bigger and better was needed.

That arrived at the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, Scotland, in November 2021, in the form of a partnership between South Africa, European countries, and the US. Together, they made a deal to deliver $8.5 billion in loans and grants to help speed up South Africa’s transition to renewables, and to do so in a socially and economically just way.

This agreement was the first of what’s being called Just Energy Transition Partnerships, or JETPs, an attempt to catalyze global finance for emerging economies looking to shift energy reliance away from fossil fuels in a way that doesn’t leave certain people and communities behind.

Featured VideoMIT Professor Explains Nuclear Fusion in 5 Levels of Difficulty

Most Popular

- BackchannelThe Dark History Oppenheimer Didn’t ShowNgofeen Mputubwele

- SecurityThe Last Hour of Prigozhin’s PlaneMatt Burgess

- ScienceThe Battle Against the Fungal Apocalypse Is Just BeginningMaryn McKenna

- SecurityA New Attack Impacts Major AI Chatbots—and No One Knows How to Stop ItWill Knight

Since South Africa’s pioneering deal, Indonesia has signed an agreement worth $20 billion, Vietnam one worth $15.5 billion, and Senegal one worth $2.75 billion. Discussions are taking place for a possible agreement for India. Altogether, around $100 billion is on the table.

There’s significant enthusiasm for JETPs in the climate finance arena, particularly given the stagnancy of global climate finance in general. At COP15 in Copenhagen in 2009, developed countries signed up to a goal of mobilizing $100 billion of climate finance for developing countries per year by 2020. None have met that target, and the agreement lapses in 2025. The hope is that more funding for clear-cut strategies and commitments will lead to quicker moves toward renewables.

South Africa came into the JETP agreement with a reasonably mature plan for a just energy transition, focusing on three sectors: electricity, new energy vehicles, and green hydrogen. Late last year, it fleshed that out with a detailed Just Energy Transition investment plan. Specifically, the plan centers on decommissioning coal plants, providing alternative employment for those working in coal mining, and accelerating the development of renewable energy and the green economy. It is a clearly defined but big task.

South Africa’s coal mining and power sector employs around 200,000 people, many in regions with poor infrastructure and high levels of poverty. So the “just” part of the “just energy transition” is critical, says climate finance expert Malango Mughogho, who is managing director of ZeniZeni Sustainable Finance Limited in South Africa and a member of the United Nations High-Level Expert Group on net-zero emissions commitments.

“People are going to lose their jobs. Industries do need to shift so, on a net basis, the average person living there needs to not be worse off from before,” she says. This is why the project focuses not only on the energy plants themselves, but also on reskilling, retraining, and redeployment of coal workers.

In a country where coal is also a major export, there are economic and political sensitivities around transitioning to renewables, and that poses a challenge in terms of how the project is framed. “Given the high unemployment rate in South Africa as well … you cannot sell it as a climate change intervention,” says Deborah Ramalope, head of climate policy analysis at the policy institute Climate Analytics in Berlin. “You really need to sell it as a socioeconomic intervention.”

That would be a hard sell if the only investment coming in were $8.5 billion—an amount far below what’s needed to completely overhaul a country’s energy sector. But JETPs aren’t intended to completely or even substantially bankroll these transitions. The idea is that this initial financial boost signals to private financiers both within and outside South Africa that things are changing.

Using public finance to leverage private investment is a common and often successful practice, Mughogho says. The challenge is to make the investment prospects as attractive as possible. “Typically private finance will move away from something if they consider it to be too risky and they’re not getting the return that they need,” she says. “So as long as those risks have been clearly identified and then managed in some way, then the private sector should come through.” This is good news, as South Africa has forecast it will need nearly $100 billion to fully realize the just transition away from coal and toward clean vehicles and green hydrogen as outlined in its plan.

Most Popular

- BackchannelThe Dark History Oppenheimer Didn’t ShowNgofeen Mputubwele

- SecurityThe Last Hour of Prigozhin’s PlaneMatt Burgess

- ScienceThe Battle Against the Fungal Apocalypse Is Just BeginningMaryn McKenna

- SecurityA New Attack Impacts Major AI Chatbots—and No One Knows How to Stop ItWill Knight

Will all of that investment arrive? It’s such early days with the South African JETP that there’s not yet any concrete indication of whether the approach will work.

But the simple fact that such high-profile, high-dollar agreements are being signed around just transitions is cause for hope, says Haley St. Dennis, head of just transitions at the Institute for Human Rights and Business in Salt Lake City, Utah. “What we have seen so far, particularly from South Africa, which is the furthest along, is very promising,” she says. These projects demonstrate exactly the sort of international cooperation needed for successful climate action, St. Dennis adds.

The agreements aren’t perfect. For example, they may not rule out oil and gas as bridging fuels between coal and renewables, says St. Dennis. “The rub is that, especially for many of the JETP countries—which are heavily coal-dependent, low- and middle-income economies—decarbonization can’t come at any cost,” she says. “That especially means that it can’t threaten what is often already tenuous energy security and energy access for their people, and that’s where oil and gas comes in in a big way.”

Ramalope says they also don’t go far enough. “I think the weakness of JETPs is that they’re not encouraging 1.5 [degrees] Celsius,” she says, referring to the limit on global warming set as a target by the Paris Agreement in 2015. In Senegal, which is not coal-dependent, the partnership agreement is to achieve 40 percent renewables in Senegal’s electricity mix. But Ramalope says analysis suggests the country could achieve double this amount. “I think that’s a missed opportunity.”

Another concern is that these emerging economies could be simply trapping themselves in more debt with these agreements. While there’s not much detail about the relative proportions of grants and loans in South Africa’s agreement, St. Dennis says most of the funding is concessional, or low-interest loans. “Why add more debt when the intention is to dramatically catalyze decarbonization in a very short timescale?” she asks. Grants themselves are estimated to be a very small component of the overall funding—around 5 percent.

But provided they generate the funding needed to bring emissions down as desired, the view of JETPs is largely positive, says Sierd Hadley, an economist with the Overseas Development Institute in London. For Hadley, the concern is whether JETPs can be sustained once the novelty has worn off, and once they aren’t being featured as part of a COP or G20 leadup. But he notes that the fact that the international community has managed to deliver at least four of the five JETP deals so far—with India yet to be locked in—shows there is pressure to make good on the promises.

“On the whole, the fact that there has been a plan, and that that plan is broadly in progress, suggests that on balance this has been fairly successful,” he says. “It’s a very significant moment for climate finance.”

Updated 8-23-2023 10:00 am BST: The location of the Komati Power Station relative to Johannesburg was corrected.

March 12th 2023

The War in Ukraine Upended Energy Markets. What Does That Mean for the Climate?

Almost a year after Russia launched its invasion, assessing the impact on the oil industry and greenhouse gas goals is not so simple.

By David Gelles

Published Jan. 14, 2023Updated Jan. 16, 2023

This article is part of our special report on the World Economic Forum’s annual meeting in Davos, Switzerland.

As world leaders, chief executives and nonprofit leaders descend on Davos, Switzerland, for the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum next week, war will be raging about 1,000 miles away.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine almost one year ago has reordered the geopolitical landscape, sent ripples through the global economy and brought trench warfare back to Europe.

Yet beyond the enormous human suffering and catastrophic damage inflicted on Ukraine, its people and its cities, one of the war’s most profound impacts has been on global energy markets, and by extension, on the global fight against climate change.

For much of the last year, the effects of war sent energy prices soaring in many parts of the world, with Europe hit particularly hard.

Even without that market, Russia remains an energy giant. And coal has had a resurgence, subduing hopes for meeting goals to rein in greenhouse gas emissions.

Yet the outlook is not all grim, and nearly a year into the war, the story is not so simple. The Ukraine invasion has had mixed results when it comes to energy and climate, particularly in the long term.

More on the World Economic Forum

Davos Confronts a New World Order

A United Europe Weathers Crises, but Deeper Challenges Remain

Across Europe, gas bills nearly doubled and electricity costs spiked some 70 percent in the first six months of the war, according to the Household Energy Price Index, which tracks energy costs.

Costs were driven up for a variety of reasons. European countries began weaning themselves off Russian fossil fuels in a bid to inflict pain on Vladimir V. Putin’s economy. In turn, Russia sharply reduced its oil exports to European countries and in July cut natural gas exports to Europe.

But with supplies tight on the global market, Russia was able to remain a dominant exporter even without Europe, selling more of its supply to China and India over the last year.

The State of the War

- Bakhmut: Ukraine insisted that its forces were fending off relentless Russian attacks in Bakhmut, even as Western analysts said that Moscow’s forces had captured most of the embattled city’s east and established a new front line cutting through its center.

- Russian Strikes: Moscow fired an array of weapons, including its newest hypersonic missiles, in its biggest aerial attack on Ukraine in weeks, knocking out power in multiple regions.

- Fields Sown With Bombs: Farmers in southern Ukraine have lost three seasons of planting to the war. With mines and cluster bombs widely scattered, normal harvests seem far in the future.

- Nord Stream Pipelines: The sabotage of the pipelines in September has become one of the central mysteries of the war. A Times investigation offers new insight into who might have been behind it.

“In the short term, Russia has been a winner because of the increase in the price of oil,” said Daniel Yergin, vice chairman of S&P Global and an energy historian.

What’s more, with European countries scrambling to buy gas and oil from other sources, energy costs began to spike. That had the effect of pushing some countries to turn to coal.

“Today’s energy crisis has given countries like India and China a reason to accelerate their coal plans,” said Jason Bordoff, cofounding dean of the Columbia Climate School at Columbia University.

Editors’ Picks

‘Saturday Night Live’ Goes to the OscarsA Knitwear Sensation at 83Bob Dylan, at 81, Still Gives the Camera What It Wants

Altogether, that was not a good scenario for the climate, which continues to rapidly warm as a result of fossil fuel consumption.

The vast majority of climate scientists say that in order to limit the extent of the warming, humans should transition to renewable energy as fast as possible.

High prices and short supplies prompted calls to produce more fossil fuels, and for a time it looked as if decades of progress in combating climate change would be erased.

But that might not be so.

While Russia managed to sell its oil and gas elsewhere in recent months, it has lost the European market for the foreseeable future.

“Putin has destroyed 22 years of economic integration with the West. And he has also slammed the door on his most important market, which is Europe,” Mr. Yergin said. “This is the last gasp of Russia as an energy superpower.”

More important, the war — and the sudden unreliability of Russia as an energy exporter — has prompted many countries to accelerate their development of renewable energy.

From England to Spain to Albania, countries across the European continent are rushing to deploy wind and solar power at record rates.

“Notwithstanding the fact there is a bit more coal being burned by Europe, Europe is doubling down on green. Notwithstanding the fact that India is buying up every bit of cheap Russian fossil fuels that it can, Asia is investing in green,” said Rachel Kyte, the dean of the Fletcher School at Tufts University.

“There is this sort of short-term supply shock story, but the moral of the story is that you don’t want to be dependent on fossil fuels. The moral of the story is to be as green as possible.”

The European Union is working to streamline permitting for renewable projects, countries are racing to build wind and solar farms, and some countries, including Germany, are slowing plans to phase out nuclear energy.

“On balance, the energy crisis we’re experiencing now, which is the most severe we’ve seen since the ’70s, is going to accelerate the clean energy transition,” said Mr. Bordoff. “It’s probably going to have a negative impact on emissions in the near term, but a positive impact in the longer term.”

Among the banks and financial firms that fund the energy industry, a similar dynamic is playing out. While many financial institutions have embraced environmental, social and governance goals — also known as E.S.G. — that include reducing the amount of capital they commit to fossil fuels, some have relaxed those restrictions.

“Some of the banks have moved away from some of their E.S.G. commitments over the last year, simply because of the urgency of addressing the energy crisis,” said Ian Bremmer, founder of Eurasia Group, a research and consulting firm.

At the end of the day, however, Mr. Bremmer believes that, “long term, all of this does redound to a faster transition to renewables.”

There are caveats.

While Europe and the United States, for example, have the money to rapidly build wind and solar capacity, poorer countries in Africa and Asia are scrambling to meet their immediate needs.

“I fear that this energy crisis will accelerate the clean energy transition in the developed world, but not in the developing world,” Mr. Bordoff said.

And in the United States, the past year was also a story of short-term energy shocks and a longer term investment in renewable power. Gas prices spiked in 2022 as oil markets tightened. Oil reserves were depleted as the Biden administration tried to bring down gas prices last year, and will need to be replenished in the years ahead.

At the same time, President Biden signed into law the Inflation Reduction Act, which includes a record $370 billion in spending and tax credits to fight climate change.

While prices have stabilized and Europe has so far benefited from a relatively mild winter, there are nagging concerns about the future. Even as European countries embrace renewable power, it will be years before those sources can fully replace fossil fuels.

“Europe is already on course to get through this winter,” Mr. Yergin said. “The big worry now, and we’ll hear this at Davos, is next winter, when they won’t have any Russian gas to put into storage.”

And while that is a dire scenario, it only reinforces what many experts say is one of the key lessons of the war so far: that renewable energy is not just good for the climate, but good for national security, too.

“If we were less dependent on globally traded oil and gas,” Mr. Bordoff said, “we would be more energy secure.”

February 9th 2023

Turkey-Syria earthquake: A catastrophe waiting to happen

Joe Attard 09 Feb 2023

- Turkey-Syria earthquake: A catastrophe waiting to happen Joe Attard 9 February 2023

- Solidarity with Peruvian workers and peasants! Down with the coup! Socialist Appeal 16 January 2023

- Ireland: Republicanism and Revolution – “The rich always betray the poor” Wellred Books 1 December 2022

- China: Anti-lockdown protests light powder keg of fury Bu Aidao 29 November 2022

- Liberal democracy: Fighting back or fracturing? Ben Gliniecki 25 November 2022

The recent earthquake in Turkey has caused widespread devastation, with thousands confirmed dead. But this was not simply a ‘natural’ disaster. Profiteering construction bosses, warmongers, and the corrupt Erdogan regime are all to blame.

Early on the morning of Monday 6 February, a devastating earthquake shook the Middle East, ripping the earth apart and reducing buildings to rubble. The magnitude 7.8 quake, with its epicentre just to the west of Gaziantep in Turkey’s Anatollian region, is the strongest to hit the country in modern times. With the strength of 130 atomic bombs, it was felt as far away as Greenland.

The initial earthquake and its 145 aftershocks wreaked destruction in southeastern Turkey and northwestern Syria, claiming the lives of an estimated 16,000 people (so far), with tens of thousands injured. The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that, when the dust clears, 20,000 people might have died.

As ever with such tragedies, the immediate cause may have had a natural origin, but the level of death and suffering was man made. Profiteering, corruption and imperialist war conspired to turn a long-expected seismic event into an utter catastrophe.

The working class must reject cynical appeals to so-called ‘national unity’, and instead point the finger squarely at the real culprits, and organise to put their murderous mismanagement to an end.

Rescuers struggled to dig people out of the rubble of collapsed buildings in a ‘race against time’ as the death toll from an earthquake across a wide area of Turkey and Syria passed 5,000.

The 7.8 magnitude quake was the deadliest in Turkey since 1999 https://t.co/DfUltmOjAW pic.twitter.com/rdVc06fhfA — Reuters (@Reuters) February 7, 2023

“We are without hope”

The earthquake struck with cruel timing for both Turkey and Syria. Turkey has been enduring skyrocketing inflation, collapsing living standards, and intensifying attacks on democratic rights from the regime. Meanwhile, Syria is still bleeding from a thousand wounds inflicted by the civil war, the flames of which were fanned by imperialism.

Hundreds of thousands of people were suddenly left homeless, in freezing conditions, desperately trying to locate lost friends and relatives. A man in Elbistan, a town near the epicentre, posted a video of piles of rubble, crying out: “This was our main high street. We are without hope.”

The northwest of Syria, which is home to hundreds of thousands of internally displaced refugees, took the brunt of the quake in that country. Entire villages have simply ceased to exist, including Basina in the Idlib province, which aerial images now show to be nothing but a pile of debris.

There are dozens of heartbreaking videos of people cradling dead fathers, mothers, siblings, and small children, or calling to trapped loved ones suffocating in the rubble.

In Aleppo, thousands of casualties have been reported in a city that was already torn apart by years of war. Entire neighbourhoods were in total ruins before Monday, and much of the damaged and dilapidated infrastructure still standing was simply flattened by the quake, including essential buildings like hospitals.

Survivors are without water or electricity, while official and civilian emergency response teams struggle against cold weather and heavy rain to pull people out of their destroyed homes.

Damage from the civil war and continued fighting between the government and rebel groups only makes it harder to send aid to the victims, especially in rebel-held areas in the north west of Syria, which can no longer be reached from Turkey because of damage to roads, and which the Syrian government is unwilling to allow aid to reach from the south.

Not an accident

The level of destruction caused by the earthquake is not solely explained by its unusual magnitude. Obviously, the carnage of the civil war made Syria especially vulnerable. But in Turkey’s case, a major part of the blame lies with the regime, and profiteering private construction companies, who colluded in a disaster that was waiting to happen.

This earthquake was expected. Turkey sits between the North and East Anatolian Faults, and is highly prone to seismic activity. “All sane earth scientists, including me, said that this earthquake came with bells ringing years ago,” said Turkish geologist Naci Görür in a live interview on US television. “No one cared to listen to what we had to say.”

The country has been hit by a number of devastating quakes over the years, including one in 1999 with an epicentre near Izmit in the Kocaeli Province that killed around 18,000 people. That particular disaster shone a spotlight on the widespread practice of building contractors ignoring safety regulations, resulting in an outpouring of public anger, forcing the government to carry out arrests.

One such gangster, Veli Gocer, was arrested after three weeks in hiding, following telephone interviews in which he admitted to cost-cutting measures such as mixing sea sand and concrete. “I’m not a builder, I’m a poet,” he said in one of these interviews. “If I’m guilty I will pay for it, but I don’t feel guilty. I feel sorry but I’m not responsible for those deaths.”

This particular parasite was only one of a whole hive, infesting a massive system of corruption in the Turkish construction sector, which the government at the time was unwilling to probe, due to the thousands of threads tying building tycoons to the state. Meanwhile, the inept rescue and relief efforts indirectly contributed to a political crisis that ended with the fall of Bülent Ecevit’s DSP government in 2002.

Following this avoidable tragedy, reforms were promised, and new regulations implemented to protect buildings from earthquakes. However, these measures were once again undermined, not only by corruption, but also conscious government policy.

According to an article in the Toronto Star, a 2018 zoning amnesty law passed by Erdogan’s regime, saw licences given to buildings that may not have adhered to building codes – in return for a fee paid to the government. 13 million structures were legalised under this officially sanctioned system of bribery.

As president of the Istanbul Branch of the Union of Chambers of Turkish Engineers and Architects, Professor Pelin Pinar Giritlioğlu, explains:

“With the laws enacted by the central government, a system of arbitrary licensing was created for construction companies which distorted the initial urbanisation goals. The construction of structures was legal on paper but contained flaws that fuelled disasters.”

This process massively accelerated after the 2016 military coup attempt against Erdogan (the background to which remains murky), after which a huge number of state buildings and public lands were privatised, and many given to the army, possibly to purchase their loyalty against the coup-plotters.

“The policy shift led to an unregulated, untransparent system,” Giritlioğlu says. “The construction companies were also able to move as they pleased and did not comply with regulations.”

The consequence is that buildings that should have held up, and were approved by state officials (who are themselves gangsters), came crashing down.

“The South East is suffering great damage now, including public buildings such as hospitals, police stations, schools, municipal buildings, bridges and airports, all built after 2007,” Giritlioğlu adds. “And these places should be the safest in case of disaster, the places where the earthquake victims will be provided for.”

Erdogan and the construction racket

Erdogan’s bloody hands are all over this scandal. All the way back to his tenure as mayor of Istanbul, and especially as Prime Minister, he developed close ties with Turkey’s construction industry. This sector was a major driving force behind the massive economic growth in the 2000s and 2010s, on which Erdgoan and the AKP built much of their authority.

Toki, Turkey’s public housing administration, answered directly to Erdogan as prime minister, and expanded enormously under his rule. A 2014 corruption probe alleged that the government was fast-tracking building permits.

“The way the system works is that if Istanbul municipality says you can’t build in a place, Ankara can overrule it – so it makes a lot more sense if you’re a business to go to the central authority,” said Refet Gurkaynak, an economist at Bilkent University in Ankara.

At the time, the Financial Times cited two (anonymous) leading Turkish businessmen, who said bribes were “sometimes necessary” to go ahead with big construction projects. Transcripts of telephone conversations leaked to the Turkish press had construction mogul Ali Agaoglu (who was amongst those detained for questioning) referred to Erdogan as “big boss”.

All in all, it is absolutely clear that Erdogan and his cronies encouraged construction fat cats to grow fatter, and grift their way to lucrative contracts for years. As president, he passed laws that allowed them to skirt around safety regulations, so that he could benefit politically from the subsequent economic growth.

Buildings constructed according to official recommendations should be fairly resistant to collapse, even during very powerful earthquakes. The cost of Erdogan and the AKP’s sleazy dealings with profiteering construction moguls can now be counted in the thousands of corpses buried under mountains of concrete.

Hypocrisy

Erdogan has declared a three-month state of emergency in the affected areas. This will give his government extraordinary powers, immediately following the introduction of a series of laws that seek to effectively ban the main opposition party, the HDP, in the run up to the general elections in May.

The president has been manoeuvring for months to shore up support for the AKP, amidst a brutal cost-of-living crisis, including announcing a new raft of public spending (in a country where the official inflation rate is in excess of 64 percent), repression against political opponents, and the whipping up of chauvinist hatred towards Turkey’s Kurdish minority and Syrian refugees living in Turkey.

Erdogan is already in a vulnerable position, and he knows it. He might hope that a swift, decisive response could be exploited to create a politically beneficial mood of ‘national unity’, that will help him secure his position. He is also cynical enough to consider using his new emergency powers to further crush his political enemies.

But this would be a dangerous move. The people were already at their wits’ end. If there is any hint that Erdogan is exploiting this tragedy for political gain, or if any personal responsibility falls on him or his party, this disaster could have profound political consequences.

The imperialist nations have engaged in an especially disgusting display of crocodile tears, particularly over Syria: a country that was left defenceless against this earthquake following years of hellish war and sanctions at the hands of these very same crocodiles.

While rescue teams from many western nations immediately headed to Turkey, it is a very different story in Syria, where continued fighting and hostilities with the Assad regime mean that western countries are refusing to engage with the official government.

The horrendous impact of this entirely preventable disaster is yet another testament to the madness and cruelty of capitalism, in which ordinary people are literally and figuratively crushed by their reactionary rulers, and the shameless profiteering of bourgeois bloodsuckers.

As one nightmare is piled onto another, it is only a matter of time before the people take their destinies into their own hands. The only way out is the expropriation of the tycoons who treat essential infrastructure as a mere cash cow; the overthrow of the politicians who facilitate their crimes; and the building of a socialist society fit for human habitation.

Comment Erdogan was a western favourite, which is why he survived the attempted coup without damage. Politcal success stories are built on corruption and dirty dealings. Britain’s only ever honest government, led by Clement Atlee lasted 5 years before Churchill’s pandering to working class narrow mindedness and greed sent them packing.

There followed 13 years of TORY mis rule creating the far too influential global political economy from which Russia has been banned. Erdogan has become a hate figure for bresaking with NATO , obstructing Sweden & Finland’s NATO membership and pushing for a negotiated Ukraine settlement.

NATO wants Georgia and Armenia too, taking control of the Black Sea creating NATO outposts, intent on encircling Russia and ultimate regime change. The masses will never get this. They swallow the propaganda like sickly sweet sickening syrup. Erdogan for all his faults is not all to blame , but must expect WESTERN ELITE offensives for election fixing and regime change. There s also the issue of Islamists putting all their faith in God who’s alleged teachings commands them to multiply..

The Romans saw the potential of inculcating unquestioning religious escapism to protect and bond their crumbling empire. Islam was a spin off belief system. It is no defence agaisnt earth quakes. Elites love the religion driven overpopulation that cheapens life while harbouring ignorance condemning them to horrors of rolling war and poverty.. Poorly built mid to high rise housing for the poor and ignorant, in an overcrowded city on the edge of a tectonic plate was a prelude to a tragedy . It won’t be the last in poor countries like this. This scenario, at best, offers western ‘liberals’ another opportunity for virtue signalling. Syria has been a living hell because of Anglo – U.S oil grabbing wars. Syria’s continuous pounding from artillery and high explosive has done nothing to strengthen the major fault line running through the north of the country. R J Cook

February 8th 2023

The enormous heat pumps warming cities

By Evie Townend2nd February 2023

From New York City to rural Cornwall, communal heat pump networks could be the answer to decarbonising heat in both city high-rises and other hard-to-heat homes.

I

It’s another cold snap and the fields of Cornwall, in south-west England, are blanketed in snow. But down a windy lane, Ceri Simmons’ home is toasty warm. Her living room is a jungle of hanging plants and, through the kitchen, glimpses of a wood-lined studio reveal Simmons’ job as an aerial-yoga teacher. “It’s not just lovely for me to have a warm house, it’s also important for my clients,” she says.

The remote village of Stithians, close to the most south-westerly tip of the UK mainland, where the Simmons family live has become an unlikely frontier in the race to decarbonise heating. It is piloting a new approach to low-carbon heating which could be key to the rapid scale-up needed worldwide.

The project zooms out from the obstacles facing individual homeowners and designs a heat pump system that can be delivered at scale across streets, towns and cities. In doing so, it could provide a model for urban spaces across the world pondering how to decarbonise their heat systems quickly and effectively.

You might also like:

- Energy crisis: How living in a cold home affects your health

- How flooded coal mines could heat homes

- How a sand battery could transform clean energy

In the UK today, 74% of people heat their homes using gas boilers, with mostly electric heaters and oil comprising the rest. This leads the heating sector to account for a third of the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions – comparable to the emissions of all its petrol and diesel cars. Similar values are seen in the US, where around half of heating comes from gas.

To limit global warming, this needs to change drastically, and in many places, that means installing many more heat pumps. By 2030, around a quarter of UK buildings should be heated using them, according to the UK government’s climate advisory body, rising to 52% by 2050. Electrifying heating will also be key to decarbonising buildings in the US, says Melissa Lott, director of research at the Centre on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University. One study in San Francisco referred to heat pumps as the “single most impactful lever” to reducing emissions.

If the source of electricity is renewable, heat pumps themselves emit no carbon

Rather than burning a fuel, heat pumps concentrate heat energy already present in air, ground or water and pump it through a building’s pipes and radiators.

They do this with incredible efficiency, converting 1 kilowatt (kW) of electricity into 3-5kW of heat, as opposed to 1kW for a direct electrical heater and 0.9kW for a gas boiler. This means they provide practically “free heat”, says Lott. However, as with all heating systems, efficiency depends on how well the building is insulated to minimise heat loss, she notes.

If the source of electricity is renewable, heat pumps themselves emit no carbon. In the UK, almost half of the electricity provided to the national grid comes from renewable sources, compared to 20% in the US. Both countries aim for sharp increases in these percentages.

Ceri Simmons’ heat pump, seen here outside her house, now supplies all her heat and hot water from a network of pipes under the street (Credit: Evie Townend)

The Heat the Streets project in Stithians provides a whole new template for how ground source heat pumps can work.

Ground source heat pumps are more efficient than their air source counterparts. This is due to the ground having a consistent temperature. Most ground source heat pumps have a vertical piping which requires drilling of a deep, costly borehole 60-200m (200-650ft) into the ground. Alternatively, they can use a horizontal loop that is far shallower in the ground but requires a large surface area that most people don’t have, especially in cities.

What’s more, installing heat pumps tends to be the responsibility of individual homeowners. Despite incentives such as the UK’s Boiler Upgrade Scheme and US federal tax credits under Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act, there remain significant barriers to widespread rollout. There is often a lack of understanding and awareness of the technology, which, combined with large upfront costs and few trained installers, can prevent homeowners from making the change. Architecture can also be a barrier: houses also simply need enough outdoor space to install the heat pumps, something obviously lacking in flats and dense urban settings.

When a [gas] boiler breaks, there’ll now be an alternative to simply replacing it – Max Bridger

Rather than each home drilling a single borehole for a single heat pump, however, Heat the Streets uses over 200 boreholes drilled 100m (330ft) beneath the street linked to a huge communal network of horizontal, underground pipes just below street level, known as a heatmain.

Glycerol – an odourless, non-toxic, viscous liquid – is passed vertically through the boreholes to absorb heat and then circulate it in these horizontal pipes, which in turn supply heat pumps in individual properties along the whole street and, eventually, the whole neighbourhood.