https://www.bankrate.com/personal-finance/rebuild-finances-after-financial-abuse/

The Great Replacement

The 28-year-old man awaiting trial over the Christchurch massacre wrote a self-justifying screed titled “The Great Replacement.” It begins: “It’s the birthrates. It’s the birthrates. It’s the birthrates.” The 21-year-old American who allegedly killed 22 people in El Paso, Texas, left behind a four-page document outlining his motivations. Its most consistent theme is the danger of Hispanic “invaders who also have close to the highest birthrate of all ethnicities in America.” The alleged shooter adds: “My motives for this attack are not at all personal. Actually the Hispanic community was not my target before I read The Great Replacement.”

Eric Bogle – The Band Played Waltzing Matilda – YouTube

As a woman , I prefer real men , not ‘he’s for she’s’ or cowards in police uniform. Modern women love police men in uniform and lapdogs.

Roberta Jane Cook

The Dubliners: The Molly Maguires HQ – YouTube

www.youtube.com › watch

Am J Public Health. 2014 June; 104(6): e19–e26. Published online 2014 June. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301946PMCID: PMC4062022PMID: 24825225

Sasha Bates of Green Party Fame , feeding off the Everard Murder by a ‘well respected police officer.’ March 12th. ‘Men should have a curfew of 6pm so Women feel safer’

This Green Party politician wants a curfew for all men after 6pm at night. Just in case you thought I was exaggerating when I call the left deranged… Nigel Farage March 12th 2021

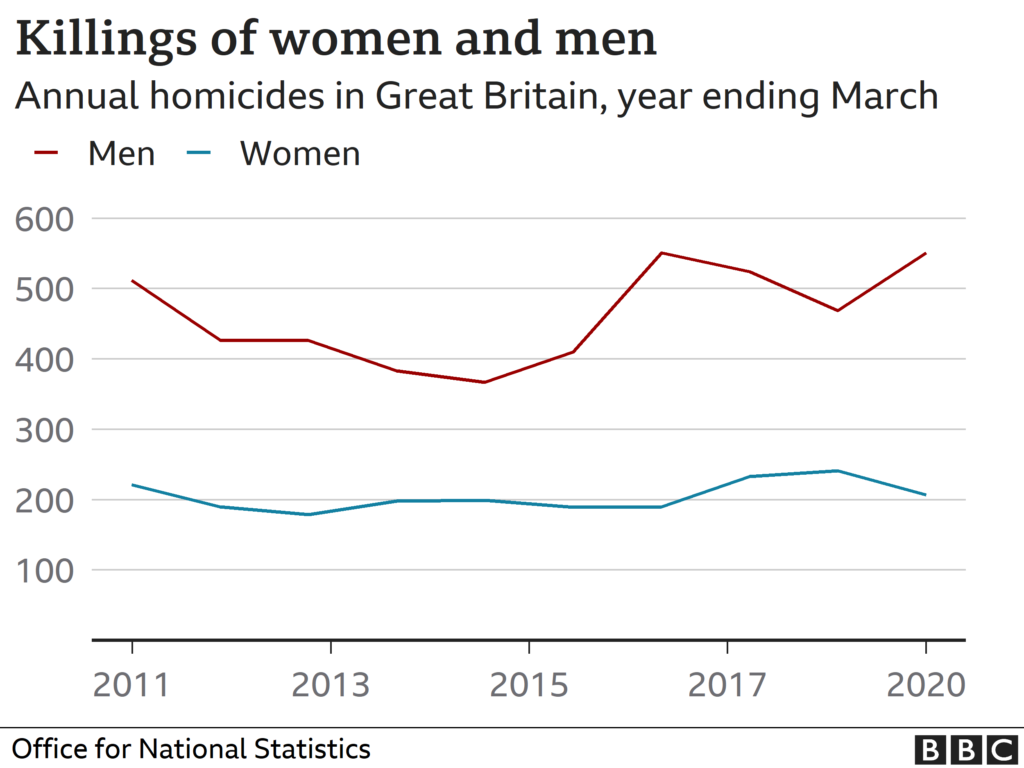

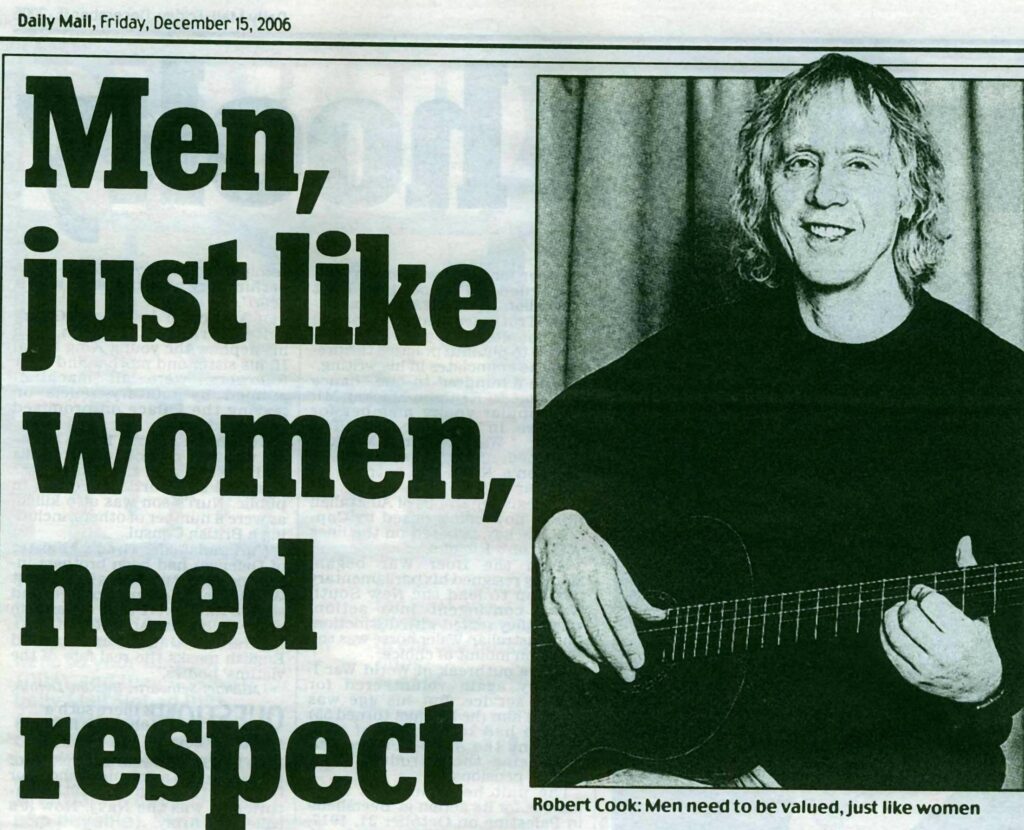

So much for equality then. The chart below, from ONS , shows very clearly that men are very much more likely to be murdered than women. The figures for men are rising with females falling. Our multi cultural cities are safe for no decent person of any race age or gender at night. Also it should be emphasised that the Everard suspect is an experienced officer from the Metropolitan Police Diplomatic Squad with sex offence form that the police refused to investigate. So if feminists are making judgements about all men, may I make adverse judgements about all police officers ?

No they are all sweet and innocent. They should be allowed to walk where they like , dressed as they like. I think roads and motorways should be closed in case they fancy J walking. This keeping people safe has taken on a whole new meaning in a geographical space claiming to be democracy but ruled by edict. Covid lockdown is paving the way for a very strange but wholesome new normal .

One last thought, it is an offence to shout at or argue with a woman because it constitutes abuse and assault. You might be lucky to get off with a charge of mansplaining. One hopes all those single parent mums will persuade more little boys to discover their ‘feminine side’ if anyone could actually explain what that is in a world where girls are ever more masculine and do not wish to be perceived as females.

There are so many contradictions and imponderables here. But never mind, just so long as we can contain all those privileged white males, where ever you find them , maybe in the pubs, the dole queue, sleeping rough , in jails or mental hospitals. There is always gender reassignment , but what does that mean when the aim is to kill white male identity and confidence and boost girls?

If you make them into girls but don’t except MTF sex changers as female then you have made a bad situation worse. Never mind , we all know sex change has a correlation with psychosis — so maybe they will all just kill themselves. BAME are nicer people and will soon make up the numbers. That is why BLM must be respected. R,J Cook

Obviously the Everard killing is a chance for more anti white male hate policies and declamations. Mustn’t mention BAME crimes or that the killer in this case was no ordinary man. He was what cops like to be called : ‘A well respected police officer.’

The matriarchy is on the march and just the right sort of cover and distraction the greedy billionaires who really run our fake democracies, love.

Women have never been made to feel so special. Everything would , of course, run so much better if they were in charge. Why not retrain sex workers as cops, whoring experience would surely be a positive and they should stop drawing attention to female sexuality. Chaperones should also be mandatory. But let’s have male safe spaces too because only a moron or liar would dare say women never lie or do wrong unless a male leads or forces them.

R.J Cook

Female Equality ( Supremacy ) means more control by elite because women do not question them or their rules. R.J Cook March 11th 2021

Women are more likely than are men to follow guidelines outlined by medical experts to prevent the spread of COVID-19, new research finds.

In an article published in Behavioral Science & Policy, New York University and Yale University researchers report that women have practiced preventive practices of physical distancing, mask wearing, and maintaining hygiene to a greater degree than men. Women were also more likely to listen to experts and exhibit alarm and anxiety in response to COVID-19.

The findings are consistent with pre-pandemic health-care behaviors, the study’s authors note.

“Previous research before the pandemic shows that women had been visiting doctors more frequently in their daily lives and following their recommendations more so than men,” explains Irmak Olcaysoy Okten, a postdoctoral researcher in NYU’s Department of Psychology and the paper’s lead author. “They also pay more attention to the health-related needs of others. So it’s not surprising that these tendencies would translate into greater efforts on behalf of women to prevent the spread of the pandemic.”

The study’s authors, who also included Anton Gollwitzer, a researcher at Yale University, and Gabriele Oettingen, a professor in NYU’s Department of Psychology, compared women and men in endorsing preventive health practices during the peak period of the pandemic in the U.S.

The researchers’ conclusions are based on three studies that employed various methodologies: a survey, on-the-street observations in different sites, and a county-level analysis of movement through GPS data from approximately 15 million smart-phone coordinates.

In the survey, researchers queried nearly 800 U.S. residents using Prolific — a research platform where individuals are compensated to complete short tasks. Questions asked about respondents’ tendency to keep social distance and to stay at home (excluding shopping), frequency of hand washing, number of days of in-person contact with family or friends, and number of days of in-person contact with others.

In all their responses, women were more likely than were men to report following these practices; in all but one of these (in-person contact with others), the differences were statistically significant.

The survey also asked about which sources of information the respondents relied on for one particular behavior — social distancing. Notably, women were significantly more likely than men to rely on the following sources when deciding to what extent they distance themselves physically from others: medical experts, other countries’ experiences, their governor, and social media.

In addition, women were much more likely then were men to attribute their behaviors to feeling anxious about the pandemic and their own health history as well as to feeling a responsibility to both themselves and to others.

In a second study, researchers observed a total of 300 pedestrians in three different U.S. locations by zip code (New York City/10012, New Haven, Conn./06511, and New Brunswick, NJ/08901) and tallied proper mask-wearing by covering the mouth and nose. They found a greater, and statistically significant, proportion of mask wearing among women (57.7 percent) than men (42.3 percent) — even though the gender distribution living in these zip codes was roughly equal.

In a final study, researchers compared overall movement as well as visits by men and women to nonessential retailers across U.S. counties. Nonessential retailers included restaurants, spas, fitness facilities, and florists, among others.

To do this, they analyzed aggregated GPS location data from approximately 3,000 U.S. counties and 15 million GPS smart-phone coordinates between March 9 and May 29. These numbers were obtained from Unacast, a company that collects mobility data from adults who have provided their consent. The researchers also took into account the fact that social distancing policies were instituted around mid-March and loosened toward the middle and end of April; as a result, social distancing increased and then decreased over time across these counties.

The results showed that tracked individuals in counties with a higher percentage of males showed comparatively less social distancing as the COVID-19 pandemic progressed between March 9 and May 29, as measured both by movement and by visits to nonessential retailers. In this analysis, the researchers considered the tracked sample as representative of a county’s overall gender break-down.

These differences remained even after accounting for COVID-19 cases per capita in these counties, the presence of stay-at-home orders, and other demographic characteristics of the counties, such as income, education, and profession.

The authors acknowledge that the findings could have been driven by men and women holding jobs that differ — specifically, men could be more likely to hold jobs in certain sectors deemed essential and therefore exhibit greater movement. However, taking into account counties’ percentages of employment in various types of professions did not alter the differences in behavior between genders. Specifically, the results were unchanged when they controlled for counties’ percentage of workers in a long list of job areas — agriculture, mining, utilities, construction, manufacturing, wholesale trade, retail trade, health care and social assistance, and hospitality and food services, among others.

The researchers also considered the possible impact of political orientation. Notably, however, the effect of gender distribution on reduced physical distancing over time did not substantially decrease when they accounted for counties’ percentage of votes for Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton in 2016.

“Fine-tuning health messages to alert men in particular to the critical role of maintaining social distancing, hygiene, and mask wearing may be an effective strategy in reducing the spread of the virus,” says Olcaysoy Okten.

Story Source:

Materials provided by New York University. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Comment There is no scientific basis for lockdown controlling the virus. Angry support from females is essential to this appalling abuse of thinking people’s rights and livelihoods. The elite have got it covered. To argue with a woman is abuse. If it takes place in the home it is domestic violence . This is the age of La Sacred Femme. She is Devine and Mystical and Sexual and Sensual. She can create life, and nourish it. She is your mother, your sister, your …daughter etc. We are in very dangerous waters with this. Outcomes are there for those who want to see. mothers are more likely to kill and abuse childred , but it is misogyny to challenge women for their behaviour.

The criteria for domestic violence and sex offences have gotten ever easier to convict, especially since there is no legal requirement for evidence or statute of limitation. This has been women’s week, with British Feminazis across the political spectrum insisting that offences against women are a whole Mount Everest higher than already exaggerated figures suggest. The evidence is there with record numbers of one parent mothered families and maladjusted children , along with rising youth suicide. White people are the most lacking in family structure as women are encouraged to ‘be themselves.’.

Those who criticise the London Tavistock Gender Identity Clinic for giving sex change hormones to 10 year olds, miss the point that the feminazis – though ironically extreme Terf feminazis see sex change as boys plotting ultimate disguise to commit rape in ladies toilets – realise getting little boys young will prevent them developing any sympathy and understanding for so , called privileged white males.

As we see in the above article , too many young men are not towing the covid line and should be in the queue for lobotomy or anti psychotic drugs and reprogamming. Nothing must get in the way of global reset propaganda. We are all supposed to accept that we can only trust infection rates when they are made to look as if they are rising. Otherwise we are told we need more data. We are also told that we can’t really ease the restrictions or ever actually get rid of them because if we did millions would die almost instantly.

We are told that vaccines are important but we will never get rid of lockdown restrictions which will at best be intermittent, but we will never close borders to illegal economic migrants. We are told in the U.K that NHS staff are heroic, then they threaten to strike if they don’t get a 15% pay rise, while the rest of us are thrown permanently out of work. Meanwhile the girls are doing their bit, making them ideal candidates to be listened to always or face abuse charges. They are so nice that they should always be promoted and leaders. Young men need to change , especially whites because they are the one who have to give up their alleged power. They must listen to the old past it experts. R.J Cook

Toxic Feminism Posted March 10th 2021

Essay, Culture Wars, Philip Carl SalzmanJuly 11, 2018

Feminism began as a challenge to male domination and female subordination. It could have become a champion of equality and the dignity of individual human beings. Unfortunately, contemporary feminism is not a liberation from sexism. It is true that feminism rejects anti-female sexism. But in place of anti-female sexism, it does not advocate gender-blind standards; it does not advocate treating individuals as complex human beings; it does not reject reducing people to their sex/gender. On the contrary, feminism, as indicated by its name, is a movement that sees people as defined by their gender, and lobbies for the interests of females. In short, feminism does not reject sexism, but advocates anti-male sexism.

In complement to feminism’s framing of females as oppressed by males, while having their qualities of strength and intelligence underrated by men, men are framed as arrogant and insensitive, oppressive, and brutal. The systematic vilification and demonization of males is part of the feminist strategy of raising women by lowering men, by convincing people that women are good and men are bad. Note that this is simply a reversal of anti-female sexism into anti-male sexism. All males, whatever their individual qualities, are reduced to a common set of evil characteristics, while all females are celebrated as sensitive, smart, and strong.

Female victimhood is described in many feminist works. Here is one well known example, as seen through the eyes of the female protagonist in a short story: I snuck Reviving Ophelia [by Mary Pipher] from my mother’s nightstand and learned how I was going to lose myself, that my childhood was Eden but I had to leave, that in this poisonous late-twentieth-century misogynist culture, anorexia and suicide and rape and self-hate were the inevitable wages of womanhood.[1]

But acclaimed Canadian fiction writer Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, together with its television version, now in its second year, is probably better known, and the dystopian picture it presents is even more dire: Offred is a Handmaid in the Republic of Gilead, a totalitarian and theocratic state that has replaced the United States of America. Because of dangerously low reproduction rates, Handmaids are assigned to bear children for elite couples that have trouble conceiving. Offred serves the Commander and his wife, Serena Joy, a former gospel singer and advocate for “traditional values.” Offred is not the narrator’s real name. Handmaid names consist of the word “of” followed by the name of the Handmaid’s Commander. Every month, when Offred is at the right point in her menstrual cycle, she must have impersonal, wordless sex with the Commander while Serena sits behind her, holding her hands. Offred’s freedom, like the freedom of all women, is completely restricted. She can leave the house only on shopping trips, the door to her room cannot be completely shut, and the Eyes, Gilead’s secret police force, watch her every public move.[2]

The Republic of Gilead is a creation of the imagination, and is about as far from modern Western society as one could imagine. It is an attempt to think how people, in this case women, could survive and adjust to an extreme situation. But Atwood is a self-identified and celebrated feminist. What is her message to women in this work? Is she saying that men can never be trusted, and women, for their own self defense, should take control of society and keep men well away from power? If so, is that an appropriate message for 20th and 21st century Canada and America? The feminist tactic appears to be, once again, scaring women and demonizing men.

Another overt feminist anti-male expression is the demand that heterosexual females forgo intimate relations with men in favour of “political lesbianism.”[3] Here is how it is defined in a pamphlet entitled “Love Your Enemy?”: “All feminists can and should be lesbians. Our definition of a political lesbian is a woman-identified woman who does not fuck men.”[4] Political lesbianism is not a matter of sexual inclination; it is not about women attracted only to women. “It does not mean compulsory sexual activity with women.” Rather, the point is “to get rid of men from your beds and your heads.”[5] Female students at some distinguished American women’s colleges were under feminist peer pressure not to date men.[6]

Feminism classifies all men, with the exception of gays, into three categories: rapists, sexual harassers, and potential rapists and harassers. Feminism does not explain this male criminality in biological terms, because feminists reject the biological basis of sex, so that women cannot be seen to be limited by biological influences. Rather, male sexual brutality is explained as a result of our so-called misogynist “rape culture.” This is an incoherent and false idea, because our culture forbids and punishes rape.[7] The #MeToo movement, a litany of unsubstantiated claims of having been sexually harassed, is another strategic step in vilifying all men, and, by contrast, claiming innocent virtue and victimhood for all women. While some men are abusive and should be stopped, #MeToo, like “rape culture,” colours all men as abusive or potentially abusive. This provides a basis in “safety” for feminists to call for greater priority for women in all fields and the sidelining of men.[8]

Feminist particularism is shown clearly by the constantly repeated demand that when a woman makes an allegation, she must be believed. Hillary Clinton, during her campaign for the U.S. Presidency, tweeted “Every survivor of sexual assault deserves to be heard, believed, and supported.”[9] Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who self-identifies as a feminist, asserts that we should “believe all allegations.”[10]

American universities and colleges responded to President Obama’s directive to prosecute sexual assault cases vigorously by jettisoning due process and the presumption of innocence.[11] At McGill University, any female who makes an allegation of sexual assault is officially labelled a “survivor.” At McGill, there is apparently a presumption of truth in any allegation, and the presumption of innocence of the accused is disregarded.[12]

What we know is that, when those accused of sexual assault are brought to court, rather than being lynched by university committees, the cases are often thrown out due to lack of evidence and credibility, and in some cases, the accusers are shown to have lied, and in some cases are indicted and sent to jail.[13]

If feminists thought of human beings as individuals, rather than as members of one good and one bad category, they might realize that many, perhaps most people lie, and that any allegation must be tested rigorously if we are concerned about justice and about avoiding punishing innocent individuals. Unfortunately, feminists are not all concerned about avoiding punishing the innocent.

“No, we haven’t gone too far, nor far enough. Male privilege, male hegemony and male chauvinism has been around for millennia all the while women and girls carrying the burden and paying the price for doing nothing but being female. The only way to change the equation is for men to begin paying that price, guilty or not.”[14] Margaret Atwood, herself a feminist literary icon, came under attack from other feminists when she called for “transparency” in inquiries about sexual assault. One critic wrote ‘Margaret Atwood’s latest op-ed is a very, very clear reminded that old cis women are not to be trusted. They care more about poor widdle [sic] accused men than they do about actual f****** rape victims. They spend as much time advocating for rapists as they do attacking victims.’ Atwood says that “she’s been called a ‘bad feminist’ for insisting on due process for Galloway, the former chair of the creative writing program, and warned the dangers of letting justice for all fall by the wayside in favor of extreme feminism.”[15] Today’s feminists apparently believe that due process and “innocent until proven guilty” are outmoded male supremacist tricks.[16]

Another unfortunate example of the feminist approach is the debate about child custody after the breakdown of a marriage. After a long-standing policy in Canada and the U.S. of favouring mothers for custody and fathers for child support payments, more recent discussion has focussed on joint custody and its advantages. Most scientific studies show that the best interests of children are served by joint custody. Children without fathers in their lives suffer a wide range of ill effects. Citing a host of North American studies, Kruk’s report points to the long-term dangers: Some 85 percent of youth in prison are fatherless; 71 percent of high school dropouts grew up without fathers, as did 90 percent of runaway children. Fatherless youth are also more prone to depression, suicide, delinquency, promiscuity, drug abuse, behavioural problems and teen pregnancy, warns the 84-page report, a compilation of dozens of studies around divorce and custody, including some of his own research over the past 20 years.[17]

But whenever legislation supporting joint custody is being considered, feminist groups such as the National Organization of Women, the League of Women Voters, Breastfeeding Coalition, National Council of Jewish Women, and UniteWomen FL, lobby and demonstrate against it.[18] In Canada, feminist lawyers have argued against joint custody.[19] In both Canada and the U.S., feminists, disregarding the best interest of children, have energetically opposed joint custody as the default arrangement for children in broken marriages. Feminists prefer to support the best interests of mothers rather than those of children. For feminists, once again, gender trumps all other values, even the well-being of children.

Feminists are never shy of demanding that gender representation in any organization or activity reflect the demography of the general population. Our self-proclaimed feminist Prime Minister proudly celebrates his gender balanced cabinet having an equal number of females to males.[20] But the pressure to favour females does not end with equal gender representation. We see this in Canadian universities, where 60 percent of the graduates are female.[21] In the United States,

On a national scale, public universities had the most even division between male and female students, with a male-female ratio of 43.6-56.4. While that difference is substantial, it still is smaller than private not-for-profit institutions (42.5-57.5) or all private schools (40.7-59.3). … It should also be noted that the national male-female ratio for 18-24 year olds is actually 51-49, meaning there are more (traditionally) college-aged males than females.[22]Do not imagine that there have been any feminist calls for the gender ratio in universities to be rebalanced.

At McGill University, the classes I taught showed an increased female dominance. In fall 2017, my senior seminar on “Immigration and Culture” had 18 registrants, all female. All of the social sciences and humanities departments, the entire Faculty of Arts, are demographically dominated by females, just as feminist ideology dominates in that Faculty, as well as in Education, Social Work, and Law. My female colleagues insisted on hiring only other females, which is pretty much what happened. There is also a major McGill campaign, complete with banners all around campus, to celebrate female scientists and direct female studies into STEM fields.[23]

But feminists are not just looking for a female demographic increase in science. They are also looking for an ideological transformation; they are advocating “feminist science,” which is “socially just science,” which should supersede objective observation and testing.[24] “Feminist science” should work at least as well as “Soviet democracy” and “scientific racism.”[25]

Female demographic domination of universities does not end with student numbers. The female Principal of McGill recently bragged that “Currently, 50 percent of McGill’s deans are female. As of July 1, when two new appointments take effect, that number will increase to 58 percent.”[26] Apparently gender imbalance is not a bad thing, when it favours females. If the trend continues, McGill University will end up a completely female institution.

A feminist lawyer invented the idea of “intersectionality,”[27] which not only identifies multiple gender, race, and class “oppressions” suffered by particular individuals, but also advises that radicals of disaffected groups unite to undermine alleged oppressors. This has led to some remarkable incoherencies, such as the alliance of feminism with Islamist Palestinians and their male supremacism and subjection of women,[28] and with antisemites such as Louis Farrakhan, black nationalist and leader of the Nation of Islam.[29] Intersectionality brings blacks to identify with “people of colour” Palestinians, and against “white” Israelis, because they identify on the basis of imagined race, in spite of Arab slave raiding in Africa and the fact that blacks are called “abid,” or slave, in the Arab world.[30]

It is difficult to know how many individuals who self-identify as feminist hope only to be treated fairly as individuals, and how many, whether implicitly or explicitly, take a female supremacist view. Certainly the feminist organizations act as if they take a supremacist approach. The net effect of toxic feminism is to reduce complex human individuals to simplistic gender categories, to dismiss all values but the partisan interests of females, and to endorse anti-male sexism.

Europe was a whore’s paradise, not just the politicians ! March 7th 2021

Someone once said, caan’t recall who but maybe it was me ‘The Penis is a gun, the balls are the magazine. When it finds a target, it will shoot. It thinks it is shooting life, not death.

Feminism is fighting nature. feminism is about empowerment. It is for the lower class masses. It is about taking power from the already increasingly hopeless men. Whores are legal in Germany, relieving the tension of male doom and social hypcrisy.

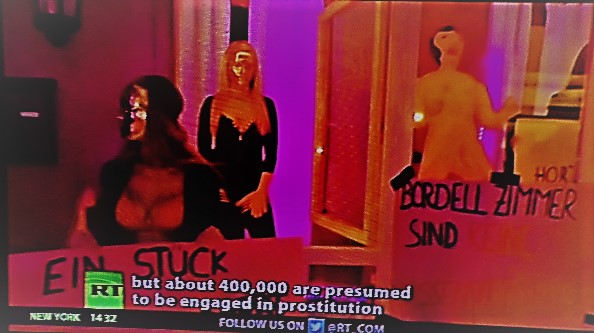

This German brothel is expecting to remain closed for a second Christmas at a time when randy young Muslim and African immigrants along with cheating business types would be overflowing in this sexual emporium.

Desperate starving German prostitutes are now going back outside into danger, desperate to earn a living during lockdown. Beneifits are not enough for living expenses which have been inflated by mass immigration raising prices. On the plus side, those young Muslim migrants want a lot of sex and their benefits are good.

This long term German brothel owner is worried for the future of his business.

They want a more feminist friendly army. To them , men, especially white ones , are the real and universal enemy. They are not clear what they want men to be except always wrong. So men seek escape with prostitutes , a world of fanatasy. Of course there are different levels of service, depending on the size of your wallet, taste and the extent of the woman’s despersation. The world has changed so much, there are even prostitutes for today’s ‘independent strong’ women.

Image Appledene Photographique.

Empowering Women Will Solve All The World’s Problems March 7th 2021

Empowering working women to subdue working men to keep the really powerful elite very safe. March 7th 2021

Here is a definition for you : ‘Empowerment includes the action of raising the status of women through education, raising awareness, literacy, and training and also give training related to self defense. Women’s empowerment is all about equipping and allowing women to make life-determining decisions through the different problems in society.’

Now let’s get anthropological and look at Ethiopia. Now don’t blame that country’s dictatorship because it is black. Black is good. No, the answer is to give women more power and Ethiopia will be good. Just slap the men down.

‘The purpose of this ( UNICEF ) study is to uncover the role of empowering women and achieving gender equality in the sustainable development of Ethiopia. To achieve this purpose, the researcher employed qualitative methodology, with secondary sources as instruments of data collection. Based on the data analysed, findings of the study show that the role of women across different dimensions of sustainable development is less reflected in the country. The use of a women’s labour force in the economic development of the country is minimal. The political sphere of the country is, by and large, reserved for men alone.

The place of women in society is also relegated to contributing minimally to the social development of the country. In addition, women’s rights are not properly being protected in order for women to participate in various the issues of their country but are subjected to abysmal violations. Moreover, women are highly affected by environmental problems, and less emphasis is given to their participation in protecting the environment.

The researcher concluded that unless women are empowered and gender equality is achieved so that women can play their role in economic, social, political, and environmental areas, the country will not achieve sustainable development with the recognition of only men’s participation in all these areas. The fact that women constitute half the entire population of the country makes empowering them to be an active part of all development initiatives in the country a compelling circumstance. Hence, this paper calls for the strong commitment of the government to empower women and utilize all the potentials of the country to bring about sustainable development.’

Obviously the solution is to confine men to manual labour and sperm donations. They are the root of all evil, this study suggests.

Roberta Jane Cook

Jilly Cooper, ‘Married men are having gay affairs because they’re ‘terrified of women’ Posted March 6th 2021

1 June 2018 • 9:46am

Married men are cheating on their wives by sleeping with other men because they are “terrified of women”, erotic novelist Jilly Cooper has claimed.

Speaking at the Hay Festival, the 81-year-old author said “an adorable gay friend” of hers was surprised to find many married men using online dating sites.

“He’s just started going on the internet now and he said it is extraordinary – it is all married men wanting to have gay affairs,” said Cooper. “Do you think they are so terrified of women now it is safer to go with their own sex?”

Best known for her 1985 bestseller Riders, the first in a series of raunchy novels about upper-class polo players and show-jumpers, Cooper criticised modern men for “crying all the time” and “growing beards”.

She also suggested that recent anti-sexual harassment campaigns such as Me Too have made flirting difficult for men. “One lovely man said ‘I can’t flirt any more’. You have a mini skirt up to here, then ‘do not touch’ tattooed across your knees,” the Daily Mail quoted Cooper as saying.

Her comments have prompted a backlash on social media. Birkbeck University social science lecturer Dr Andrew Fugard branded the author a “homophobe”, while behavioral psychologist and LBC radio prsesenter Jo Hemmings wrote: “being gay isn’t a passing fad in response to women being more empowered.”

Men may have had to learn a few new behaviours (and forget others) but being gay isn’t a passing fad in response to women being more empowered/assertive. I doubt there are ANY men who have had a gay affair as a result! x— Jo Hemmings (@TVpsychologist) June 1, 2018

According to the Guardian, Cooper also hinted that she may retire from writing after her next book, a forthcoming erotic novel about footballers called Tackle. The author of more than 40 books, Cooper was awarded a CBE earlier this year for services to literature and charity.

During the same event, Cooper accused Germaine Greer of making provocative comments solely to get attention, branding the feminist author an “applause junkie.”

Greer told a Hay Festival audience earlier this week that she thought “most rape is just lazy, just careless, just insensitive”, and suggested the penalty for rape should be community service.

VCooper said: “I think [Germaine Greer] is wonderful, but she has got to the stage now where she will say something outrageous to get everyone going.”

A Very Fishy Story March 4th 2021

Salmond and Sturgeon battle: An A to Z guide to the explosive scandal at the top of Scottish politics Posted March 4th 2021

Scotland correspondent @jamesmatthewsky

Wednesday 3 March 2021 19:42, UK

Scotland’s first minister Nicola Sturgeon has given evidence at an inquiry looking into the mishandling of harassment complaints against her predecessor Alex Salmond.

Ms Sturgeon is facing calls to resign amid fresh claims she lied to parliament, following the Scottish government’s publication of legal advice about a court challenge by Mr Salmond in 2018.

Here’s who’s who – and why the Holyrood inquiry could deepen rifts at the heart of Scottish politics.

A

is for Alex Salmond, icon of the Scottish independence movement, who claims former colleagues in the party he once led tried to remove him from public life and even have him put in jail.

B

is for bitter enemies.

The Salmond/Sturgeon combo took Scotland to the brink of independence, now it’s all about acrimony. He alleges that the current first minister broke the ministerial code, she accuses him of creating an “alternative reality”.

C

is for conspiracy.

Alex Salmond says senior officials in the Scottish National Party (SNP) and Scottish government were involved in a “malicious and concerted effort” to damage his reputation.

D

is for the despair openly expressed by some members of Holyrood’s harassment committee, who accuse the Scottish government of undermining their inquiry by a failure to provide the information and cooperation they need to get to the truth.

E

is for evasion.

A number of government witnesses have been forced to correct or clarify evidence given under oath. Committee members have accused them of “evasion and secrecy”.

F

is for the Fairness at Work code, a civil servants’ complaints procedure drafted in 2010 following union concerns about bullying around the office of the then first minister Alex Salmond.

Nicola Sturgeon, as his then deputy FM, was given a role in dealing with complaints.

G

G is for Gus, or Angus Robertson.

An Edinburgh Airport manager called him in 2009 about Alex Salmond’s perceived “inappropriateness” towards female staff and he was asked to “informally broach” it with him.

Mr Salmond denied he had acted inappropriately in any way.

H

is for the harassment committee itself, which will hear evidence from Mr Salmond and Ms Sturgeon.

The committee of MSPs was set up to look into what lay behind the Scottish government’s mishandling of an internal inquiry into harassment complaints against Mr Salmond by two female civil servants.

I

is for identities.

There is a legal requirement to protect the identities of complainants in Alex Salmond’s criminal trial. There’s some crossover with the harassment inquiry, one of the reasons given for redactions in some of the published evidence.

J

is for judicial review, the court action that Alex Salmond took in 2018/19 to challenge the legality of the Scottish government’s investigation of harassment complaints against him.

He won and the taxpayer picked up a legal bill of more than £600,000.

K

is for Kenny MacAskill MP, Scotland’s former justice secretary and an ally of Alex Salmond.

He’s told Sky News of a text message in which one SNP official spoke of encouraging an alleged victim to give evidence in the criminal trial against Alex Salmond.

L

is for legal advice.

The Scottish parliament has twice voted to demand the release of government legal advice surrounding Alex Salmond’s judicial review. It hasn’t been forthcoming.

It might shed light on suggestions ministers ploughed on with a legal challenge despite being advised not to. The government points out that advice is typically subject to legal professional privilege and should remain confidential.

M

is for ministerial code, which Alex Salmond claims Nicola Sturgeon breached in a number of ways.

They include allegedly misleading parliament about when she learned of complaints against him, and failing to stop her government prolonging an expensive judicial review challenge despite legal advice it was doomed to fail.

The code dictates a minister in breach of it should offer their resignation.

N

is for Nicola Sturgeon, leader of the SNP since 2014, who has made her party a racing certainty to win the forthcoming Scottish parliament elections and has helped to shape opinion polls showing unprecedented support for Scottish independence.

O

is for Operation Diem, the name of the police investigation that led to Alex Salmond’s arrest on criminal charges.

He was acquitted after a High Court trial in March 2020 of 13 sexual assault charges against nine women.

P

is for Peter Murrell, SNP chief executive and husband of Nicola Sturgeon.

Alex Salmond claims he deployed SNP staff to “recruit” staff and ex-staff to submit police complaints about him. Mr Murrell has denied plotting against Mr Salmond.

Q

is for questions that everyone’s asking.

Among them is James Hamilton, Ireland’s former director of public prosecutions, who is an independent adviser on Scotland’s ministerial code.

As such, he’s the man conducting a parallel investigation into whether the first minister breached it. His conclusions are due in the coming weeks.

R

is for redacted.

Parts of Alex Salmond’s written submission to the harassment committee have been redacted, which means he could have difficulty referring to those subject areas in his oral evidence – and they are central to claims that Nicola Sturgeon broke the ministerial code.

S

is for sex crimes and the reporting of them.

Rape Crisis Scotland has said that aspects of the inquiry, and some of the written submissions that have been published, have undermined efforts to improve women’s confidence in reporting crimes such as sexual harassment.

T

is for the twenty-ninth of March 2018.

Did Nicola Sturgeon discuss complaints against Alex Salmond during a meeting in her office?

Sky News revealed a first-hand account of a meeting in Nicola Sturgeon’s office where complaints against Alex Salmond were discussed. She told parliament she learned of them four days later.

U

is for “unlawful”.

How a judge in the Court of Session described the Scottish government’s internal investigation into harassment complaints against Alex Salmond in January 2019.

V

is for the “Vietnam Group” – the name of a WhatsApp group involving SNP members.

The Crown Office released its communications to the committee, which decided they weren’t relevant to its work. It now wants to see texts between SNP figures that Alex Salmond believes show the effort to destroy him.

W

is for Wolffe, as in James Wolffe QC, Scotland’s lord advocate.

As head of the Crown Office and the government’s chief legal adviser, he was summoned to parliament to deny opposition claims of political influence in redacting parts of Alex Salmond’s written evidence.

X

is for the cross on the ballot paper.

How will the fallout from this saga affect the SNP at the 6 May Scottish parliament elections?

Y

is for Yes, the independence campaign that took Scotland to the brink of breaking away from the UK in 2014.

In the event of an Indyref2, how far will the Sturgeon/Salmond split fracture the independence movement itself?

Z

is for zero chance of an outcome to this inquiry that suits everyone.

There’s every chance, however, that widespread dissatisfaction with the process will damage the parliament itself – what opposition MSPs have called a “crisis of credibility”.

Women’s Ultimate Weapon March 3rd 2021

It is a fact of life that women can destroy any man with sexual or violence allegations. Even when a man is found innocecent, the women’s rights groups , with press in thrall, are out in force proclaiming that another guilty man has gone free. The only possible way for a man to limit risk is to avoid being alone with women and avoid any unnecesary interaction. A man must also be very careful with language.

There is of course no way of avoiding risk with wives and girlfriends and no statute of limitations for when allegations might be made. Women say they do not want to be viewed sexually unless they choose the man on their terms. No wonder there is such a demand for viagra that it is no longer restricted to prescription and there is a big TV campaign for men to take it to please ‘their women.’

So viagra is effectively a date rape drug for men who don’t want or need sex. Women’s movements thrive on statistics for sex and violence complaints taken as truth because ‘women never lie’ ( sic ),as well as posh women not getting the ‘top job’ that they deserve. So this culture is here for the foreseeable future. The following report should be read with this in mind.

Roberta says women are doing a lot to create a mightmare and lonely world for themselves. ” It reminds me of the joke about ‘Divorced Barbie’. She comes with all of Ken’s stuff.

“Staying safe is a con. Follow all the rules and there will be no excitement . Humans, hiding from real problems that the ruling class doesn’t want them to see, are going mad for obvious reasons . They won’t be able to cope with real problems when they come”.

Nicola Sturgeon has rejected the “absurd” allegation the Scottish government plotted to destroy Alex Salmond’s reputation but admitted it made serious mistakes in its investigation into complaints against him.

The first minister said her government made a “dreadful, catastrophic mistake” during its inquiry into two sexual harassment complaints against Salmond by appointing an official who had previously spoken to the complainers as its investigation officer.

That decision led to the government losing a judicial review taken by Salmond, costing taxpayers more than £600,000. “Two women were failed and taxpayers’ money was lost,” she said. “I deeply regret that.”

Closely questioned by MSPs during a marathon eight-hour evidence session at the Scottish parliament, Sturgeon insisted her former mentor was wrong to accuse her, the Scottish National party, or her officials of a vendetta or conspiracy against him.

“I must rebut the absurd suggestion that anyone acted with malice or as part of a plot against Alex Salmond,” she said in her opening statement to nine MSPs investigating the government’s botched inquiry into the harassment allegations against Salmond, which he had denied.

She later went further: “Alex Salmond has been for most of my political life, since I was 20, 21 years of age, my closest colleague. He was someone I looked up to, someone I revered. I would never have wanted to ‘get’ Alex Salmond.”

Sturgeon came under pressure from MSPs to explain why there had been repeated delays in the release of the government’s legal advice, and key internal documents, as she offered new explanations about why she had met Salmond while the harassment inquiry was under way.

Jackie Baillie, of Labour, alleged Sturgeon and Salmond had breached the confidentiality of complainers when he discussed their allegations against him in a meeting at her home on 2 April 2018, yet Sturgeon waited until early July before telling Leslie Evans, the permanent secretary, they had met.

Sturgeon acknowledged she discussed Salmond’s criticisms of the inquiry with him five times partly because she felt loyalty towards him, but delayed telling Evans because she feared that would be seen as her interfering in the process.

Labour and Conservative MSPs accused Sturgeon’s deputy first minister, John Swinney, of breaking the government’s promises to publish all its legal advice, despite his last-minute decision to release previously secret legal papers late on Tuesday afternoon. Several weeks of legal meetings were missing from the records Swinney released; Sturgeon promised more papers would be supplied.

Those papers contained the explosive revelation that Roddy Dunlop QC, one of Scotland’s leading lawyers, who was the government’s external counsel, had been furious that government officials failed to disclose critical evidence about the prior contact of the investigating officer with the two complainants.

Sturgeon told the committee she only learned of this apparent conflict of interest and its legal significance in November 2018.

In a parallel development, the Tories said they were reconsidering their votes of no confidence against Swinney and Sturgeon, due to be heard on Thursday, after Swinney offered to release more legal information. The party said the motions were still live, but indicated they might be withdrawn.

Sturgeon was pressed on whether she had investigated allegations that a senior government official had leaked the name of a complainer to Geoff Aberdein, Salmond’s former chief of staff, before Sturgeon met Aberdein in her office at Holyrood in late March 2018.

Aberdein’s account was supported by Salmond’s lawyer Duncan Hamilton and his former spokesman Kevin Pringle, who told the committee on Tuesday Aberdein had made that claim in a conference call with him soon after he met that official.

The Tory MSP Murdo Fraser said that was “an incredibly serious issue” and potentially unlawful. Sturgeon said Aberdein’s account had been denied by the official concerned but she said the allegation was included in an investigation by James Hamilton, Ireland’s former director of public prosecutions, into whether Sturgeon broke the ministerial code.

“That was not the way, as I understand it, that happened, in the way that is being set out,” she said.

During a series of tense exchanges, Sturgeon said she had no idea who leaked news that the internal inquiry upheld the complaints against Salmond to the Record newspaper in August 2018, despite his allegations a government figure must be to blame.

“There was no part of me that wanted for this proactively to get into the public domain,” she said. The idea she would ever need to discuss this publicly made her feel “physically sick”.

She also admitted that before she met Salmond at her home in April 2018, she “had a lingering fear, suspicion, concern” that allegations about his conduct might emerge. She knew Sky News had contacted the government in early November 2017 about alleged incidents involving Salmond at Edinburgh airport a decade earlier – claims Salmond denied – and had discussed them with him that month.

Answering Salmond’s charges that she offered to intervene on his behalf in the government inquiry, Sturgeon said Salmond might have misunderstood what she said to him.

Her written evidence said she made clear to him she would not intervene, but Duncan Hamilton, who was present when Sturgeon met Salmond in her house on 2 April, told the committee in written evidence on Tuesday that he heard her offer to do so “if it comes to it”.

Sturgeon said Salmond may have misunderstood. “I believe I made it clear I wouldn’t intervene. [I] was perhaps trying to let a longstanding friend and colleague down gently, and maybe I did it too gently, and maybe he left with an impression I didn’t mean to give him.”

The first minister said once Salmond had set out the allegations he was facing “my head was spinning. I was experiencing a maelstrom of emotions.”

Sturgeon said the government had to investigate the allegations against Salmond, regardless of how powerful or famous he might be. She said many people, including her, had been let down by her former friend and mentor but he had not yet apologised.

“When I saw him lashing out on Friday, I don’t know whether he ever reflects on the fact that many of us feel let down by him,” she said. “That is a matter of deep personal regret.”

The Sexual Victimization of Men in America: New Data Challenge Old Assumptions Posted February 26th 2021

Lara Stemple, JD and Ilan H. Meyer, PhDAuthor informationArticle notesCopyright and License informationDisclaimerThis article has been cited by other articles in PMC.Go to:

Abstract

We assessed 12-month prevalence and incidence data on sexual victimization in 5 federal surveys that the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation conducted independently in 2010 through 2012. We used these data to examine the prevailing assumption that men rarely experience sexual victimization. We concluded that federal surveys detect a high prevalence of sexual victimization among men—in many circumstances similar to the prevalence found among women. We identified factors that perpetuate misperceptions about men’s sexual victimization: reliance on traditional gender stereotypes, outdated and inconsistent definitions, and methodological sampling biases that exclude inmates. We recommend changes that move beyond regressive gender assumptions, which can harm both women and men.

The sexual victimization of women was ignored for centuries. Although it remains tolerated and entrenched in many pockets of the world, feminist analysis has gone a long way toward revolutionizing thinking about the sexual abuse of women, demonstrating that sexual victimization is rooted in gender norms1 and is worthy of social, legal, and public health intervention. We have aimed to build on this important legacy by drawing attention to male sexual victimization, an overlooked area of study. We take a fresh look at several recent findings concerning male sexual victimization, exploring explanations for the persistent misperceptions surrounding it. Feminist principles that emphasize equity, inclusion, and intersectional approaches2; the importance of understanding power relations3; and the imperative to question gender assumptions4 inform our analysis.

To explore patterns of sexual victimization and gender, we examined 5 sets of federal agency survey data on this topic (Table 1). In particular, we show that 12-month prevalence data from 2 new sets of surveys conducted, independently, by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) found widespread sexual victimization among men in the United States, with some forms of victimization roughly equal to those experienced by women.

TABLE 1—

US Federal Agency Surveys of Sexual Victimization Using Probability Samples

| Study | Year of Study | Conducted by | Sample | No. |

| National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS) | 2010 | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | Nationally representative telephone survey of 12 mo and lifetime prevalence data on sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence | 16 507 |

| National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) | 2012 | Bureau of Justice Statistics | Longitudinal survey of US households | 40 000 households |

| ∼75 000 | ||||

| Uniform Crime Report (UCR) | 2012 | Federal Bureau of Investigation | NA (UCR is a cooperative statistical effort whereby 18 000 city, university, and college, county, state, tribal, and federal law enforcement agencies report data on crimes brought to their attention.) | NA |

| Sexual Victimization in Prisonsa and Jails Reported by Inmates; National Inmate Survey (NIS 2011–12) | 2011–2012 | Bureau of Justice Statistics | Probability sample of state and federal confinement facilities and random sampling of inmates within selected facilities | 92 449 |

| Sexual Victimization in Juvenile Facilitiesa Reported by Youth; National Survey of Youth in Custody (NSYC 2012) | 2012 | Bureau of Justice Statistics | Multistage stratified survey of facilities in each state of the United States and random sample of youths within selected facilities | 8707 |

Note. NA = not available.aIn these reports, 12-month prevalence refers to 12 months, or shorter if the respondent has been in the facility for less than 12 months.

Despite such findings, contemporary depictions of sexual victimization reinforce the stereotypical sexual victimization paradigm, comprising male perpetrators and female victims. As we demonstrate, the reality concerning sexual victimization and gender is more complex. Although different federal agency surveys have different purposes and use a wide variety of methods (each with concomitant limitations), we examined the findings of each, attempting to glean an overall picture. This picture reveals alarmingly high prevalence of both male and female sexual victimization; we highlight the underappreciated findings related to male sexual victimization.

For example, in 2011 the CDC reported results from the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS), one of the most comprehensive surveys of sexual victimization conducted in the United States to date. The survey found that men and women had a similar prevalence of nonconsensual sex in the previous 12 months (1.270 million women and 1.267 million men).5 This remarkable finding challenges stereotypical assumptions about the gender of victims of sexual violence. However unintentionally, the CDC’s publications and the media coverage that followed instead highlighted female sexual victimization, reinforcing public perceptions that sexual victimization is primarily a women’s issue.

We explore 3 factors that lead to misperceptions concerning gender and sexual victimization. First, a male perpetrator and female victim paradigm underlies assumptions about sexual victimization.6 This paradigm serves to obscure abuse that runs counter to the paradigm, reinforce regressive ideas that portray women as victims,7 and stigmatize sexually victimized men.8 Second, some federal agencies use outdated definitions and categories of sexual victimization. This has entailed the prioritization of the types of harm women are more likely to experience as well as the exclusion of men from the definition of rape. Third, the data most widely reported in the press are derived from household sampling. Inherent in this is a methodological bias that misses many who are at great risk for sexual victimization in the United States: inmates, the vast majority of whom are male.9,10

We call for the consistent use of gender-inclusive terms for sexual victimization, objective reporting of data, and improved methodologies that account for institutionalized populations. In this way, research and reporting on sexual victimization will more accurately reflect the experiences of both women and men.Go to:

MALE PERPETRATOR AND FEMALE VICTIM PARADIGM

Roberta’s Image by Appledene Photographics.

The conceptualization of men as perpetrators and women as victims remains the dominant sexual victimization paradigm.11 Scholars have offered various explanations for why victimization that runs counter to this paradigm receives little attention. These include the ideas that female-perpetrated abuse is rare or nonexistent,12 that male victims experience less harm,8 and that for men all sex is welcome.13 Some posit that because dominant feminist theory relies heavily on the idea that men use sexual aggression to subordinate women,14 findings perceived to conflict with this theory, such as female-perpetrated violence against men, are politically unpalatable.15 Others argue that researchers have a conformity bias, leading them to overlook research data that conflict with their prior beliefs.16

We have interrogated some of the stereotypes concerning gender and sexual victimization, and we call for researchers to move beyond them. First, we question the assumption that feminist theory requires disproportionate concern for female victims. Indeed, some contemporary gender theorists have questioned the overwhelming focus on female victimization, not simply because it misses male victims but also because it serves to reinforce regressive notions of female vulnerability.17 When the harms that women experience are held out as exceedingly more common and more worrisome, this can perpetuate norms that see women as disempowered victims,7 reinforcing the idea that women are “noble, pure, passive, and ignorant.”13(p1719)

Related to this, treating male sexual victimization as a rare occurrence can impose regressive expectations about masculinity on men and boys. The belief that men are unlikely victims promotes a counterproductive construct of what it means to “be a man.”18 This can reinforce notions of naturalistic masculinity long criticized by feminist theory, which asserts that masculinity is culturally constructed.19 Expectations about male invincibility are constraining for men and boys; they may also harm women and girls by perpetuating regressive gender norms.

Roberta’s image copyright Appledene photographics.

Another common gender stereotype portrays men as sexually insatiable.13 The idea that, for men, virtually all sex is welcome likely contributes to dismissive attitudes toward male sexual victimization. Such dismissal runs counter to evidence that men who experience sexual abuse report problems such as depression, suicidal ideation, anxiety, sexual dysfunction, loss of self-esteem, and long-term relationship difficulties.20

A related argument for treating male victimization as less worrisome holds that male victims experience less physical force than do female victims,21 the implication being that the use of force determines concern about victimization. This rationale problematically conflicts with the important feminist-led movement away from physical force as a defining and necessary component of sexual victimization.22 In addition, a recent multiyear analysis of the BJS National Crime Victim Survey (NCVS) found no difference between male and female victims in the use of a resistance strategy during rape and sexual assault (89% of both men and women did so). A weapon was used in 7% of both male and female incidents, and although resultant injuries requiring medical care were higher in women, men too experienced significant injuries (12.6% of females and 8.5% of males).23

Portraying male victimization as aberrant or harmless also adds to the stigmatization of men who face sexual victimization.8 Sexual victimization can be a stigmatizing experience for both men and women. However, through decades of feminist-led struggle, fallacies described as “rape myths”24 have been largely discredited in American society, and an alternative narrative concerning female victimization has emerged. This narrative teaches that, contrary to timeworn tropes, the victimization of a woman is not her fault, that it is not caused by her prior sexual history or her choice of attire, and that for survivors of rape and other abuse, speaking out against victimization can be politically important and personally redemptive.

For men, a similar discourse has not been developed. Indeed contemporary social narratives, including jokes about prison rape,25 the notion that “real men” can protect themselves,8 and the fallacy that gay male victims likely “asked for it,”26 pose obstacles for males coping with victimization. A male victim’s sexual arousal, which is not uncommon during nonconsensual sex, may add to the misapprehension that the victimization was a welcome event.27 Feelings of embarrassment, the victim’s fear that he will not be believed, and the belief that reporting itself is unmasculine have all been cited as reasons for male resistance to reporting sexual victimization.28 Popular media also reflects insensitivity, if not callousness, toward male victims. For example, a 2009 CBS News report about a serial rapist who raped 4 men concluded, “No one has been seriously hurt.”29

The minimization of male sexual victimization and the hesitancy of victims to come forward may also contribute to a paucity of legal action concerning male sexual victimization. Although state laws have become more gender neutral, criminal prosecution for the sexual victimization of men remains rare and has been attributed to a lack of concern for male victims.30 The faulty assertion that male victimization is uncommon has also been used to justify the exclusion of men and boys in scholarship on sexual victimization.31 Perhaps such widespread exclusion itself causes male victims to assume they are alone in their experience, thereby fueling underreporting.32

Not only does the traditional sexual victimization paradigm masks male victimization, it can obscure sexual abuse perpetrated by women as well as same-sex victimization. We offer a few counterparadigmatic examples. One multiyear analysis of the NCVS household survey found that 46% of male victims reported a female perpetrator.23 Of juveniles reporting staff sexual misconduct, 89% were boys reporting abuse by female staff.33 In lifetime reports of nonrape sexual victimization, the NISVS found that 79% of self-reported gay male victims identified same-sex perpetrators.34

Despite such complexities, as recently as 2012, the National Incident Based Reporting System (a component of the Uniform Crime Reporting Program [UCR]) included male rape victims but still maintained that for victimization to be categorized as rape, at least 1 of the perpetrators had to be of the opposite sex.35 Conversely, under the NISVS definitions, for a female to fall into the “made to penetrate” category, the perpetrating receptive partner must also be female.5 (“Made to penetrate” includes anal penetration by a finger or other object, and a female could therefore be made to penetrate a male.) Additional research and analysis concerning female perpetration and same-sex abuse is warranted but is beyond the scope of this article. For now we simply highlight the concern that reliance on the male perpetrator and female victim paradigm limits understandings, not only of male victimization but of all counterparadigmatic abuse.Go to:

DEFINITIONS AND CATEGORIES OF SEXUAL VICTIMIZATION

The definitions and uses of terms such as “rape” and “sexual assault” have evolved over time, with significant implications for how the victimization of women and men is measured. Although the definitions and categorization of these harms have become more gender inclusive over time, bias against recognizing male victimization remains.

When the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) began tracking violent crime in 1930, the rape of men was excluded. Until 2012, the UCR, through which the FBI collects annual crime data, defined “forcible rape” as “the carnal knowledge of a female forcibly and against her will” (emphasis added).36 Approximately 17 000 local law enforcement agencies used this female-only definition for the better part of a century when submitting standardized data to the FBI.37 Meanwhile, the reform of state criminal law on rape, which began in the 1970s and eventually spread to every jurisdiction in the country, revised definitions in numerous ways, including the increased recognition of male victimization. Reforms also broadened definitions to address nonrape sexual assault.38

These state revisions left a mismatch with the limited UCR definition, forcing agencies to send only a subset of reported sexual assault to the FBI. Some localities eventually refused to parse their data according to the biased federal categories. For example, in 2010 Chicago, Illinois, recorded 84 767 reports of forcible rape under UCR, but because they refused to comply with the UCR’s outdated categorization, the FBI did not include Chicago rape data in its national count.39

In 2012 the FBI revised its 80-year-old definition of rape to the following: “the penetration, no matter how slight, of the vagina or anus with any body part or object, or oral penetration by a sex organ of another person, without the consent of the victim.”40 Although the new definition reflects a more inclusive understanding of sexual victimization, it appears to still focus on the penetration of the victim, which excludes victims who were made to penetrate. This likely undercounts male victimization for reasons we now detail.

The NISVS’s 12-month prevalence estimates of sexual victimization show that male victimization is underrepresented when victim penetration is the only form of nonconsensual sex included in the definition of rape. The number of women who have been raped (1 270 000) is nearly equivalent to the number of men who were “made to penetrate” (1 267 000).5 As Figure 1 also shows, both men and women experienced “sexual coercion” and “unwanted sexual contact,” with women more likely than men to report the former and men slightly more likely to report the latter.5FIGURE 1—

Twelve-month sexual victimization prevalence (percentage) among adult population (noninstitutionalized) from the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey 2010, and among adult and juvenile detainees from the National Inmate Survey 2011–2012 and the National Survey of Youth in Custody, 2012: United States.

aAmong the 5 federal agency surveys we reviewed, only NISVS collected lifetime prevalence, limiting our ability to compare lifetime data across surveys. It found lifetime prevalence for men as follows: made to penetrate = 4.8%, rape = 1.4%, sexual coercion = 6.0%, and unwanted sexual contact = 11.7%. For women: rape = 18.3%, sexual coercion = 13.0%, and unwanted sexual contact = 27.2%.

bFemale detainees are significantly more likely to be sexually victimized by fellow detainees than are males; a presumably same-sex pattern of abuse that runs counter to the male perpetrator/female victim paradigm.

This striking finding—that men and women reported similar rates of nonconsensual sex in a 12-month period—might have made for a newsworthy finding. Instead, the CDC’s public presentation of these data emphasized female sexual victimization, thereby (perhaps inadvertently) confirming gender stereotypes about victimization. For example, in the first headline of the fact sheet aiming to summarize the NISVS findings the CDC asserted, “Women are disproportionally affected by sexual violence.” Similarly, the fact sheet’s first bullet point stated, “1.3 million women were raped during the year preceding the survey.” Because of the prioritization of rape, the fact sheet failed to note that a similar number of men reported nonconsensual sex (they were “made to penetrate”).41

The fact sheet paints a picture of highly divergent prevalence of female and male abuse, when, in fact, the data concerning all nonconsensual sex are much more nuanced. Unsurprisingly, media outlets then emphasized the material the CDC highlighted in its summary material. The New York Times headline read, “Nearly 1 in 5 Women in U.S. Survey Say They Have Been Sexually Assaulted.”42(pA32)

In addition, the full NISVS report presents data on sexual victimization in 2 main categories: rape and other sexual violence. “Rape,” the category of nonconsensual sex that disproportionately affects women, is given its own table, whereas “made to penetrate,” the category that disproportionately affects men, is treated as a subcategory, placed under and tabulated as “other sexual violence” alongside lesser-harm categories, such as “noncontact unwanted sexual experiences,” which are experiences involving no touching.5

Additionally, much more information is provided about rape than being made to penetrate. The NISVS report gives separate prevalence estimates for completed versus attempted rape and for rape that was facilitated by alcohol or drugs. No such breakdown is given concerning victims who were made to penetrate, although such data were collected. Including these data in the report would avoid suggesting that this form of unwanted sexual activity is somehow less worthy of detailed analysis.1 These various reporting practices may draw disproportionate attention to the sexual victimization of women, implying that it is a more worrisome problem than is the sexual victimization of men.

Prioritizing rape over being made to penetrate may seem an obvious and important distinction at first glimpse. After all, isn’t rape intuitively the worst sexual abuse? But a more careful examination shows that prioritizing rape over other forms of nonconsensual sex is sometimes difficult to justify, for example, in the case of an adult forcibly performing oral sex on an adolescent girl and on an adolescent boy. Under the CDC’s definitions, the assault on the girl (if even slightly penetrated in the act) would be categorized as rape but the assault on the boy would not. According to the CDC, the male victim was “made to penetrate” the perpetrator’s mouth with his penis,5(p17) and his abuse would instead be categorized under the “other sexual violence” heading. We argue that this is neither a useful nor an equitable distinction.

By introducing the term “made to penetrate,” the CDC has added new detail to help understand what happens when men are sexually victimized. But the distinction may obscure more than it elucidates. In contrast to the term “rape,” the term “made to penetrate” is not commonly used. The CDC’s own press release about the survey, for example, uses the word “rape” (or “raped”) 7 times and makes no mention of “made to penetrate.”43 In this way, “rape” is the harm that ultimately captures media attention, funding, and programmatic intervention, whereas “made to penetrate” is relegated to a secondary, somewhat obscure harm.

Similarly, the FBI’s revised UCR definition, although a distinct improvement over the 1929 female-only definition, still seems to maintain an exclusive focus on the victim’s penetration.40 Therefore, to the extent that males experience nonconsensual sex differently (i.e., being made to penetrate), male victimization will remain vastly undercounted in federal data collection on violent crime.5

This focus on the directionality of the act runs counter to the trend toward greater gender inclusivity in sexual victimization definitions over the past 4 decades. The broader and more inclusive term “sexual assault” has replaced the term “rape” in at least 37 states.44 Not only has this change been widespread in legal definitions, but it is now standard practice to avoid the term “rape” in survey questions because of inconsistencies in how respondents perceive this term.21 Some anti–sexual violence activists may resist movement away from a term as compelling and vivid as “rape,” but others have noted that victims who choose another label may do so as a legitimate coping strategy.45

We recognize that when it comes to the impact of sexual victimization, men and women may indeed experience it differently.21 But categorizing the forms of sexual victimization that men typically experience as different and lesser than the forms of victimization that women typically experience would require considered justification. The reasons for continuing such practices would need to outweigh the drawbacks we have enumerated. We do not believe that such justification has been offered in the literature.

We therefore urge federal agencies to use care when collecting and reporting data on sexual victimization to avoid biased categorization. This does not mean that we suggest treating all sexual victimization identically. Nonconsensual penetrative acts (regardless of directionality) may be legitimately distinguished from acts that do not involve penetration. Likewise, harms that do not involve any genital contact whatsoever, such as unwelcome kissing, flashing, and sexual comments, although harmful for some victims, are categorically distinguishable because they do not involve contact with socially inviolable and physically sensitive reproductive parts of the body.

Without seeking to outline an entirely new classification scheme, we posit that “rape” as currently defined by the CDC and the FBI will continue to foster the underrecognition of the extent of male victimization. Terms such as “sexual assault” and “sexual victimization,” if defined in gender-inclusive ways, have the potential to capture the kind of abuse with which federal agencies ought to be concerned. They can be used more consistently and with less gender and heterosexist bias across crime, health, and other surveys. This would facilitate important cross-population analyses that inconsistent definitions now limit.Go to:

SAMPLING BIAS

In population-based sexual victimization studies, as in many other areas, researchers use a sampling frame that is restricted to US households. This excludes, among others, those held in juvenile detention, jails, prisons, and immigration detention centers. Because of the explosion of the US prison and jail population to nearly 2.3 million people46 and the disproportionate representation of men (93% of prisoners9 and 87% of those in jail10) among the incarcerated, household surveys—including the closely watched NCVS—miss many men, especially low-income and minority men who are incarcerated at the time the household survey is conducted. Opportunities for intersectional analyses that take race, class, and other factors into account are missed when the incarcerated are excluded. For instance, characteristics such as sexual minority and disability status, including mental health problems, place inmates at risk: among nonheterosexual prison inmates with serious psychological distress, 21% report sexual victimization.47

Of course, surveys of inmate and juvenile populations present a host of ethical, legal, and logistical challenges for surveyors. Sexual victimization in particular is risky for inmates to disclose; those who report abuse may be targeted for retaliation. The challenges of including vulnerable populations are very real, but because inmates are at great risk, their exclusion is especially likely to skew the public understanding of sexual victimization. For example, the NCVS’s household data on rape and sexual assault are widely reported in the media each year but typically without mention of the impact of excluding incarcerated individuals (or other institutionalized or homeless persons).

Recognizing the lack of data concerning incarcerated persons, the 2003 Prison Rape Elimination Act mandates that BJS conduct a regular comprehensive survey about sexual victimization behind bars.48 These results help fill the gap in knowledge concerning sexual victimization in the United States. We reviewed 2 of the recently released reports (Table 1), which provide results from the National Inmate Survey 2011–2012 and the National Survey of Youth in Custody, 2012.

These 2 surveys demonstrate that male and female detainees both experience sexual victimization committed by staff and other inmates and that the prevalence differs by sex (Figure 1). The National Inmate Survey 2011–2012 shows that slightly more men than women in jails and prisons reported staff sexual misconduct, which includes all incidents of sexual contact with staff (12-month prevalence for men in jails = 1.9%, men in prisons = 2.4% vs 1.4% and 2.3%47 for women, respectively). Women in jails and prisons reported more inmate-on-inmate abuse than did men (women in jails = 3.6%, women in prisons = 6.9% vs 1.4% and 1.7% for men, respectively).

In the National Survey of Youth in Custody 2012, about 9.5% of male and female juvenile detainees reported sexual victimization in the 12 months before the interview (or since detained, if < 12 months).33 But gender differences were observed: females were more likely than were males to report sexual victimization by other youths (5.4% vs 2.2%), and males were more likely than were females to report sexual victimization by facility staff (8.2% vs 2.8%).33

The examination of data from prisons, jails, and juvenile detention institutions reveals a very different picture of male sexual abuse in the United States from the picture portrayed by the household crime data alone. This discrepancy is stark when comparing the detainee findings with those of the NCVS, the longitudinal crime survey of households widely covered in the media each year. The 2012 NCVS’s household estimates indicate that 131 259 incidents of rape and sexual assault were committed against males.49 Using adjusted numbers from the detainee surveys, we roughly estimate that more than 900 000 sexual victimization incidents were committed against incarcerated males (Figure 2).

Open in a separate windowFIGURE 2—

Annual incidents of sexual victimization from the Uniform Crime Report (UCR) and the National Crime Victim Survey (NCVS), 2012; the National Inmate Survey-2, 2008–2009; and the National Survey of Youth in Custody 2008–2009: United States.