July 8th 2023

Lucid dreaming lets you shape your dreamscape, whether your aims are practical or fantastical. These tips can get you started

A vivid dream is like a free virtual-reality experience, no expensive headset required. While your body lies tucked up in bed, your mind can take you to exotic lands and introduce you to amazing characters. If you’re lucky, you might even be granted fantastical powers, such as the ability to breathe underwater or walk through walls.

I mention luck because it can often feel as if dreams are randomly generated – the day’s events might shape the narrative, but otherwise it’s usually a case of waiting to see what your brain comes up with. But it doesn’t have to be that way: in so-called ‘lucid dreams’, it’s possible for you to have a degree of control over what happens. This opens up many options for using dreams to your advantage, such as to rehearse for real-life events, generate ideas, or simply have a whole lot of fun.

Over at the lucid dreaming channel on Reddit, for instance, choosing to fly like a bird is a particular favourite. ‘All of a sudden I was soaring up into the sky and the most intense feeling of bliss, happiness and excitement took over my body,’ wrote one user. Another recalled flying ‘over the city, the deep blue ocean and even a bunch of islands’, and deciding to evade missiles along the way.

‘A lucid dream is a dream in which you know you are dreaming,’ explains Mark Blagrove, professor of psychology at Swansea University in Wales and the co-author of The Science and Art of Dreaming (2023). ‘As a result, you can either decide to simply observe the dream with the knowledge that it’s not real or you can actually alter the content of the dream.’

People use lucid dreaming to practise all manner of real-life tasks, including rehearsing musical performances, making speeches and preparing for awkward conversations

You might have experienced a lucid dream for yourself already. Research suggests that around half of us will have the experience at least once in our lifetimes. A quarter of people have them regularly. Whichever camp you find yourself in, there are various techniques you can use to start purposefully having more lucid dreams.

Sign-up to our weekly newsletter

Intriguing articles, practical know-how and immersive films, straight to your inbox.

See our newsletter privacy policy

Reasons to lucid dream

Before trying out some of these techniques, you might be wondering if it’s safe and worth the effort. Note that, if you have sleep problems or mental health difficulties, lucid dreaming could make matters worse – so check in with a doctor or mental health expert first. If you’re good to go, there are a few enticing reasons you might want to give lucid dreaming a try. There’s some preliminary evidence that it will make your dreams more positive, thus improving your waking mood. Another small study found lucid dreaming to be associated with lower stress and higher self-esteem and life satisfaction. Most tantalising to me, though, is the idea that you could use your lucid dreams to practise skills that you need in waking life.

One researcher looking into this application is Daniel Erlacher at the University of Bern in Switzerland. Although he cautions that his investigations are preliminary, he and his colleagues have shown that people can use lucid dreams to practise a basic finger-tapping task, such that they improve as much as others who practised the task in waking life – by about 20 per cent. The research team has uncovered similar findings for darts and coin tossing. Commentators on the website Quora have claimed to use lucid dreaming to practise all manner of real-life tasks, including rehearsing musical performances, making speeches and preparing for awkward conversations. ‘I would recommend this to everyone who has lucid dreams, to use the dream state for practising sport or music or whatever,’ says Erlacher.

Other reasons for which you could use lucid dreams include to boost your creativity, for example by asking dream characters for their ideas. On his deathbed in 1920, the mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan reportedly said he’d used lucid dreams to help him solve problems. Or you could try dealing with nightmares via what’s known as ‘lucid dreaming therapy’. The basic idea in the latter case, says Erlacher, is that, when you realise you’re in a dream, you confront yourself with the kind of nightmare content that’s been troubling you, be that a creepy house, a nasty person or something else. ‘You can go there and you can say: “Hey, what are you doing here? It’s my dream,”’ Erlacher says. ‘What people describe is that the nightmare disappears, usually.’ The more control you feel you have over your dream content, the more likely it is that you will benefit from this approach.

Use a bracelet as a cue – any time you catch a glimpse of it, ask yourself: Is this real, or am I dreaming?

Ways to have more lucid dreams

Whether you’re just curious or you can already see the ways lucid dreaming might be helpful for you, here are some basic techniques to get you started:

Reality testing

The easiest approach is to get into the habit of asking yourself whether you are awake or in a dream, at least a few times each day. This technique has come to be known as ‘reality testing’. The thinking is that, if you do this often enough when you’re awake, the habit is likely to carry over into your dreams – in which case it can trigger a lucid state of being aware that you’re dreaming.

A popular way to do this, explains Blagrove, is to use a bracelet as a cue – any time during the day that you catch a glimpse of the bracelet, you ask yourself a reality-check question, such as: Is this real, or am I dreaming? ‘That questioning transfers over into the sleeping state,’ he says. Once you ask yourself the question while asleep and become aware that you are, in fact, dreaming, you can choose whether to just observe the dream or try to influence it in some way.

Another approach I’ve heard about is to check occasionally throughout the day whether you can pass the fingers of one hand through the palm of the other, which of course is impossible, thus confirming that you’re awake. Similar to the basic reality-check question, if you perform this strange ritual often enough when awake, the chances are that you’ll do it in a dream. While dreaming, it’s likely that you will be able to pass your fingers through your hand, and you might trigger a lucid state in the process.

Wake back to bed (WBTB)

With this approach, you set an alarm two to three hours before you would normally wake up. That is just the time when you’re most likely to be having rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, which is a stage of sleep that is strongly associated with having dreams. After waking, you keep yourself awake for an hour or so before you allow yourself to nod off again.

Keep a diary of common symbols or images that you experience in your dreams, and then form the lucid dreaming intention around those images

The WBTB approach aligns with what is known about the brain basis of lucid dreaming, which experts admit is fairly limited for now. The lucid dream state tends to be associated with greater frontal brain activation than non-lucid dreaming, especially during REM sleep. The WBTB approach would appear to help you target this brain state, thus increasing the odds of achieving dream lucidity. ‘What happens with this technique,’ explains Blagrove, is that ‘your sleep is much later [than normal] because you woke yourself up earlier and, as a result of the circadian rhythm, your brain is more activated. And also you’ve just deprived yourself of some sleep, so you have a much more intense rapid eye movement period occurring.’

Mnemonic induction of lucid dreams (MILD)

This approach builds on the WBTB protocol and similarly involves setting an alarm to wake a few hours before you would normally rise. In fact, Erlacher says you really ought to combine WBTB with MILD – otherwise you risk simply ending up with a bad night’s sleep.

At its most basic, the MILD technique involves waking yourself up toward the end of your usual sleep period and then forming a conscious intention to have a lucid dream when you fall back to sleep. ‘It’s a sort of self-suggestion method,’ says Blagrove. Some experts suggest repeating a mantra to yourself, such as: “The next time I am dreaming, I will remember that I am dreaming.”’

A more elaborate version of this approach is to keep a diary of common symbols or images that you experience in your dreams, and then form the lucid dreaming intention around those images. For example, if you frequently see flying cows in your dreams, you might tell yourself, prior to returning to sleep: ‘When I see a flying cow, I will know that this is the dream.’ Erlacher explains: ‘So you combine these events with the suggestion of “I will know that I’m dreaming when I see this.”’

The senses initiated lucid dream technique

This approach was proposed by a blogger and lucid dreaming enthusiast more than a decade ago, and now it’s often mentioned in the academic literature on lucid dreaming. Despite the mentions, it’s been studied only once, but the results were promising. As with WBTB and MILD, the idea is to set an alarm to wake yourself a few hours before your normal rising time.

Once awake, you close your eyes and quickly cycle through some of your senses a few times, first focusing on your sight (with eyes closed), then on what you are hearing, then tuning in to your body. After doing that a few times quickly, you then repeat the cycle a few times more, but this time slowly. Once you’ve finished the slow cycles through your senses, you let yourself fall back to sleep. It’s been claimed that you are then much more likely to have a lucid dream. The full tutorial is available online.

Targeted lucidity activation

This approach has been used recently by sleep labs to try to induce more lucid dreams, and it’s probably the most ambitious of the techniques described here. You might need to rope in your bedtime companion, if you have one, for some assistance.

Spend a few minutes reflecting, while simultaneously exposing yourself to a red flashing light or electronic beeping sound

The basic principle is this: during the day, you spend a few minutes reflecting on your thoughts, your sensations and your state of awareness (a little like ‘reality testing’), while simultaneously exposing yourself to some distinct sights or sounds, such as a red flashing light or electronic beeping sound. You’re conditioning yourself to be self-reflective when you experience these stimuli. Then, while you’re in REM sleep, you need a way to expose yourself to the sensory stimuli again. The idea is that this will nudge you to reflect on your state of mind and surroundings (but without fully waking you up), thus prompting you into a lucid state.

This is where your understanding partner could come in handy. They should be able to tell when you’re in REM sleep by watching your eyes flicker under your eyelids. Then, they might flash the red light or play the electronic sound. An alternative is to buy a fancy lucid dreaming mask that detects when you’re in REM sleep and flashes the light and/or plays a beeping sound.

‘The idea is that these sounds and visual stimuli get incorporated into the dream,’ Blagrove explains. ‘You’re never quite sure how they’ll be incorporated … it may be that there’s a red object there or that the whole scene turns red, or the electronic tune might come into the dream. But the aim is that it causes the person to ask themselves the question: Am I asleep?’

Final notes

So, there you have it: a few different ways to begin taking more control of your dreams. You might even be able to start using your dreams to benefit your waking life, such as by practising something you will be doing the next day.

As you get started, bear in mind that lucidity is not all or nothing. A recent survey found that control of your dream body is more common than complete control of the dream environment. The same study found that having more frequent lucid dreams was associated with having greater dream control – implying that practice makes perfect – and that being more mindful during the day could help, too. Good luck and sweet dreams!

June 20th 2023

byAmber DanceandKnowable Magazine

June 3, 2023

CSA Images/CSA Images/Getty Images

Maybe it starts with a low-energy feeling, or maybe you’re getting a little cranky. You might have a headache or difficulty concentrating. Your brain is sending you a message: You’re hungry. Find food.

Studies in mice have pinpointed a cluster of cells called AgRP neurons near the underside of the brain that may create this unpleasant hungry, even “hangry,” feeling. They sit near the brain’s blood supply, giving them access to hormones arriving from the stomach and fat tissue that indicate energy levels. When energy is low, they act on a variety of other brain areas to promote feeding.

By eavesdropping on AgRP neurons in mice, scientists have begun to untangle how these cells switch on and encourage animals to seek food when they’re low on nutrients and how they sense food landing in the gut to turn back off. Researchers have also found that the activity of AgRP neurons goes awry in mice with symptoms akin to those of anorexia and that activating these neurons can help to restore normal eating patterns in those animals.

Understanding and manipulating AgRP neurons might lead to new treatments for both anorexia and overeating. “If we could control this hangry feeling, we might be better able to control our diets,” says Amber Alhadeff, a neuroscientist at the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia.

To eat or not to eat

AgRP neurons appear to be key players in appetite: Deactivating them in adult mice causes the animals to stop eating — they may even die of starvation. Conversely, if researchers activate the neurons, mice hop into their food dishes and gorge themselves.

Experiments at several labs in 2015 helped to illustrate what AgRP neurons do. Researchers found that when mice hadn’t had enough to eat, AgRP neurons fired more frequently. But just the sight or smell of food — especially something yummy like peanut butter or a Hershey’s Kiss — was enough to dampen this activity within seconds. From this, the scientists concluded that AgRP neurons cause animals to seek out food. Once food has been found, they stop firing as robustly.

One research team, led by neuroscientist Scott Sternson at the Janelia Research Campus in Ashburn, Virginia, also showed that AgRP neuron activity appears to make mice feel bad. To demonstrate this, the scientists engineered mice so that the AgRP neurons would start firing when the light was shone into the brain with an optical fiber (the fiber still allowed the mice to move around freely). They placed these engineered mice in a box with two distinct areas: one colored black with a plastic grid floor, the other white with a soft, tissue paper floor. If the researchers activated AgRP neurons whenever the mice went into one of the two areas, the mice started avoiding that region.

Sternson, now at the University of California San Diego, concluded that AgRP activation felt “mildly unpleasant.” That makes sense in nature; he says: Any time a mouse leaves its nest, it’s at risk from predators, but it must overcome this fear in order to forage and eat. “These AgRP neurons are kind of the push that, in a dangerous environment, you’re going to go out and seek food to stay alive.”

Sternson’s 2015 study showed that while the sight or smell of food quiets AgRP neurons, it’s only temporary: Activity goes right back up if the mouse can’t follow through and eat the snack. Through additional experiments, Alhadeff and colleagues discovered that what turns the AgRP neurons off more reliably is calories landing in the gut.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=aTnI-uoGTcg%3Fenablejsapi%3D1%26origin%3Dhttps%253A%252F%252Fwww.inverse.com%26widgetid%3D1

The sleeping mouse in this video has been engineered so that when blue light shines into its brain, AgRP neurons are activated. The mouse is resting after a night in which it had plenty to eat. When researchers turn on the blue light, the mouse awakens and eats more, even though it’s sated.

First, Alhadeff’s team fed mice a calorie-free treat: a gel with artificial sweetener. When mice ate the gel, AgRP neuron activity dropped, as expected — but only temporarily. As the mice learned there were no nutrients to be gained from this snack, their AgRP neurons responded less and less to each bite. Thus, as animals learn whether a treat really nourishes them, the neurons adjust the hunger dial accordingly.

Next, the team used a catheter implanted through the abdomen to deliver calories, in the form of the nutritional drink Ensure, directly to the stomach. This bypassed any sensory cues that food was coming. And it resulted in a longer dip in AgRP activity. In other words, it’s the nutrients in food that shut off AgRP neurons for an extended time after a meal, Alhadeff concluded.

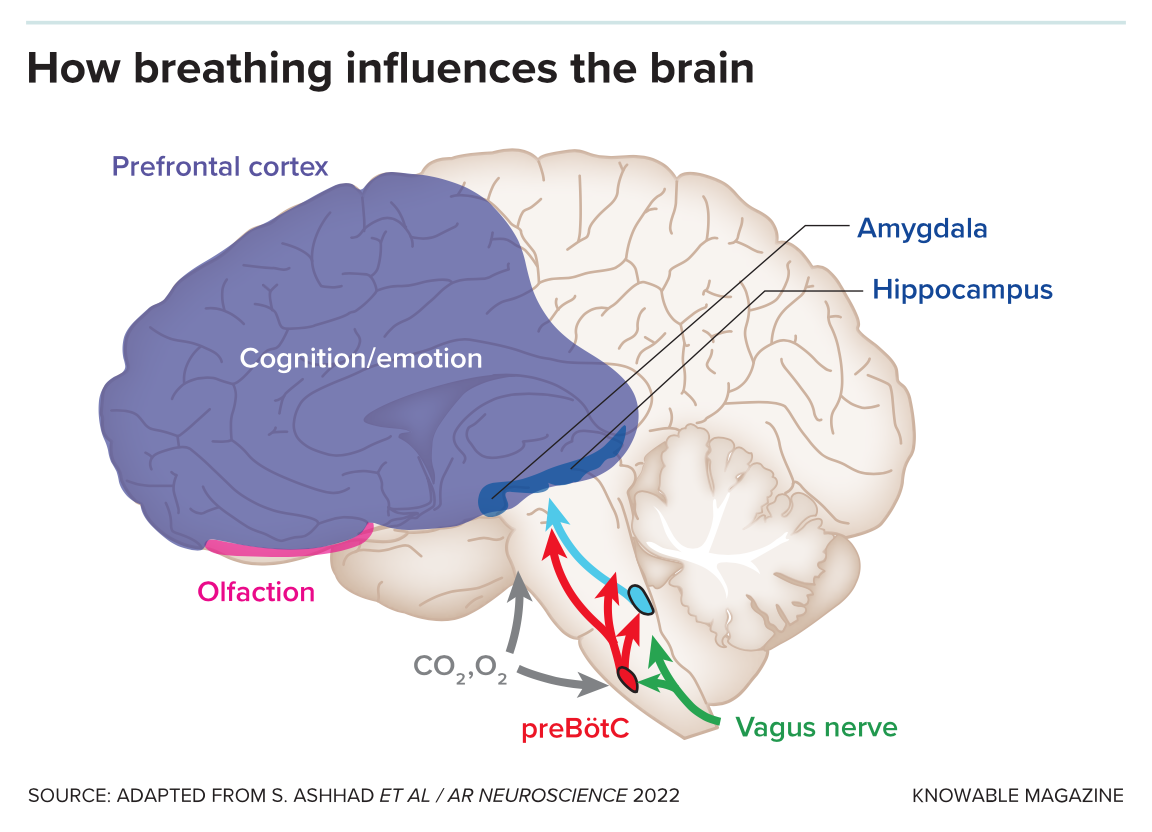

Alhadeff has since begun to decode the messages that the stomach sends to the AgRP neurons and found that it depends on the nutrient. Fat in the gut triggers a signal via the vagus nerve, which reaches from the digestive tract to the brain. The simple sugar glucose signals the brain via nerves in the spinal cord.

Her team is now investigating why these multiple paths exist. She hopes that by better understanding how AgRP neurons drive food-seeking, scientists can eventually come up with ways to help people keep off unhealthy pounds. Though scientists and dieters have been seeking such treatments for more than a century, it’s been difficult to identify easy, safe, and effective treatments. The latest class of weight-loss medications, such as Wegovy, act in part on AgRP neurons but have unpleasant side effects such as nausea and diarrhea.

Therapies targeting AgRP neurons alone would likely fail to fully solve the weight problem because food-seeking is only one component of appetite control, says Sternson, who reviewed the main controllers of appetite in the Annual Review of Physiology in 2017. Other brain areas that sense satiety and make high-calorie food pleasurable also play important roles, he says. That’s why, for example, you eat that slice of pumpkin pie at the end of the Thanksgiving meal, even though you’re already full of turkey and mashed potatoes.

Outflanking anorexia

The flip side of overeating is anorexia, and there, too, researchers think that investigating AgRP neurons could lead to new treatment strategies. People with anorexia avoid food to the point of dangerous weight loss. “Eating food is actually aversive,” says Ames Sutton Hickey, a neuroscientist at Temple University in Philadelphia. There is no medication specific for anorexia; treatment may include psychotherapy, general medications such as antidepressants, and, in the most severe cases, force-feeding via a tube threaded through the nose. People with anorexia are also often restless or hyperactive and may exercise excessively.

Researchers can study the condition using a mouse model of the disease known as activity-based anorexia, or ABA. When scientists limit the food available to the mice and provide them with a wheel to run on, some mice enter an anorexia-like state, eating less than they’re offered and running on the wheel even during daylight, when mice are normally inactive. “It’s a remarkably addictive thing that happens to these animals,” says Tamas Horvath, a neuroscientist at the Yale School of Medicine. “They basically get a kick out of not eating and exercising.”

It’s not a perfect model for anorexia. Mice, presumably, face none of the social pressures to stay thin that humans do; conversely, people with anorexia usually don’t have limits on their access to food. But it’s one of the best anorexia mimics out there, says Alhadeff: “I think it’s as good as we get.”

To find out how AgRP neurons might be involved in anorexia, Sutton Hickey carefully monitored the food intake of ABA mice. She compared them to mice that were given a restricted diet but had a locked exercise wheel and didn’t develop ABA. The ABA mice, she found, ate fewer meals than the other mice. And when they did eat, their AgRP activity didn’t decrease like it should have after they filled their tummies. Something was wrong with the way the neurons responded to hunger and food cues.

Sutton Hickey also found that she could fix the problem when she engineered ABA mice so that AgRP neurons would spring into action when researchers injected a certain chemical. These mice, when treated with the chemical, ate more meals and gained weight. “That speaks very much to the importance of these neurons,” says Horvath, who wasn’t involved in the work. “It shows that these neurons are good guys, not the bad guys.”

Sutton Hickey says the next step is to figure out why the AgRP neurons respond abnormally in ABA mice. She hopes there might be some key molecule she could target with a drug to help people with anorexia.

All in all, the work on AgRP neurons is giving scientists a much better picture of why we eat when we do — as well as new leads, perhaps, to medications that might help people change disordered eating, be it consuming too much or too little, into healthy habits.

This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine, an independent journalistic endeavor from Annual Reviews. Sign up for the newsletter.

more like this

mRNA Vaccines Could Revolutionize Cancer Treatment HealthAsymptomatic Cases Could Hold The Key To Resisting Infectious Diseases HealthSeeing Death Makes Fruit Flies Age FasterLEARN SOMETHING NEW EVERY DAY

Subscribe for free to Inverse’s award-winning daily newsletter!

By subscribing to this BDG newsletter, you agree to our Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Related Tags

May 27th 2023

How To Get People To Actually Listen To You

Master these expert techniques and you’ll break through more often.

Updated: May 17, 2023

Originally Published: April 5, 2022

It’s the universal wish when we open our mouths. We just want to be heard. And really, it shouldn’t be that complicated, although it gets that way, usually by our own doing. We pick the wrong time or place, forgetting other people have lives and busy schedules.

Still, we proceed, trying to force our message on unreceptive ears. We start raising our voices, interrupting, and finishing other people’s sentences, none of which has ever been taught in Effective Communications 101.

While saying something as simple as, “Is now okay to talk?” can solve some problems, the larger issue centers on expectations. It’s not solely men, but a lot of men certainly believe that when they have something to say, it must be said immediately.

“By default, men get the stage. They demand to be listened to,” says Sylvia Mikucki-Enyart, associate professor of communication studies at the University of Iowa.

That attitude doesn’t set a welcoming stage. While there are practical things to do to effectively communicate, the bigger shift comes in adjusting your approach. Rather than see an interaction as being listened to, it’s better to view it as an exchange between two people, either of whom can influence the direction. With that mindset, the pressure to get everything out dissipates.

How do you get to that place? Paying close attention to the following can help.

1. Be Willing to Listen

This shouldn’t be surprising. If you want someone to hear you, you have to do the same. Sure, it’s polite, but you’re not merely reciting words and then leaving. The other person is part of it. They need to feel like a part of it, and even if you’re already close, there needs to be a connection for that moment.

“There’s no better way to do that than to listen to someone else,” says Bill Rawlins, professor emeritus of interpersonal communications at Ohio University.

And it’s not easy, because you really, really, really want to say something. There’s no secret about what to do. It’s discipline and reminding yourself to not speak and catching yourself when you start.

“It’s always a dedication,” Rawlins says.

2. Watch Out For “Kitchen Sinking”

Sometimes you’re not making your point because you haven’t figured it out, so you just say everything in a rambling mess. Mikucki-Enyart calls this “kitchen sinking.” But when you practice out loud, you’ll hear the words that matter and the ones that can be cut. If you’re heated, repetition gets you used to the emotion and lowers the intensity so the first time you say something is not the first time you say something.

And if it helps, have notes about issues you want to hit and reminders to stay calm or not interrupt. Be upfront and let the person know that you don’t want to forget anything. You’d do all of this prep for a business meeting and no one would question it.

“I don’t know why we expect our relational communications to fly by the seat of our pants,” she says.

3. Learn to Pause

Part of effective talking is not talking. Yes, you want to give the other person the floor, but even before that, it’s allowing the other person to take in your words and gauge what your message means to them. Again, it’s a kind of listening and involves “not trying to formulate your next sterling moment in the conversation,” Rawlins says.

But you can use the pause as well. It’s your chance to consider what’s being said, which can reshape what you share. Just let the person know that you’re thinking. Silence can make people feel uneasy and an inhale can come off as frustration or boredom when it’s just taking in air. If you see the same from the other person, just ask, let them clarify and remove unnecessary wonder.

“It’s perception checking,” says Mikucki-Enyart.

4. Embrace the “Vivid Present”

Men tend to be definitive. Michael Jordan is the best. The Godfather is the greatest movie ever. But conversations are live and involve you and the other person. Practicing helps gets you comfortable, but it’s not a scripted event. More than acknowledging and accepting that, embrace what the two of you share.

Rawlins says that Austrian philosopher Alfred Schutz called that space the “vivid present”. Make a comment about the weather, wall colors, or traffic, whatever is connecting the two of you right then and there, and then the conversation is no longer about fighting for time or to be heard.

“It’s neither mine nor yours,” Rawlins says. “It’s between us.”

What helps is to ask questions along the way. What do you think about what just happened? How do you feel about what I just said? People usually like to get questions. They allow them to talk, and these, which can’t be shut down with a “yes” or “no” answer, are an invitation to stay involved.

5. Treat Each Conversation As Its Own

Communicating skills aren’t inherent. “It’s not a trait,” Mikucki-Enyart says. They can be learned and bolstered, but each time you go into a conversation, you’re going into that specific conversation. It takes a brand new focus and attention to detail. You may need to vent. You might want advice. The same goes for the other person. It’s like how you’d approach sports or music. It means bringing the effort while reading what the environment is like because what worked yesterday might not work today.

“You need to re-consecrate yourself,” Rawlins says. “You have to show up. A lot of it is will. Every moment has a possibility of showing something to us.”

more like this

Want To Be More Trustworthy? Master These 5 SkillsBig MomentsThe Big Realization That Made Me A Better Dad, According To 10 Men

Not subscribed to Fatherly’s newsletter yet? We’re not mad, just disappointed.

By subscribing to this BDG newsletter, you agree to our Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

This article was originally published on April 5, 2022

May 15th 2023

How to Make Your Anxiety Work for You Instead of Against You

Anxiety is energy, and you can strike the right balance if you know what to look for.

- Stephanie Vozza

Read when you’ve got time to spare.

Advertisement

More from Fast Company

- This counterintuitive trick can help you be more effective at work

- 4 steps to regaining your focus when you’re totally stressed out

- It’s time to reframe our thoughts around anxiety. Here’s how to use it productively

Advertisement

Photo by Feodora Chiosea/Getty Images.

While some cases of anxiety are serious enough to require medical treatment, everyday anxiety is a fact of life and can actually be helpful, says psychologist Bob Rosen, author of Conscious: The Power of Awareness in Business and Life.

“How you use it makes all the difference,” he says. “As the world gets faster and more uncertain, it’s easy to let [anxiety] overwhelm you. People get hijacked by their reptilian brain survival instincts and fear. On the flip side, denying or running from anxiety causes you to become complacent. You can use anxiety in a positive way and turn it into a powerful force in your life if you strike a balance.”

The first hurdle to get over is viewing anxiety through a negative lens. “We see anxiety as something to fear and avoid,” says Rosen. “That thinking is self-defeating and makes it worse. In a sense, we need to see anxiety as a wake-up call; a message inside of our mind telling us to pay attention. We need to accept it as a natural part of the human experience.”

Another problem is our faulty thinking around change, says Rosen. “For centuries, it was viewed as dangerous or life threatening,” he says. “But stability is an illusion, and uncertainty is reality. Uncertainty makes you anxious and vulnerable, and anxiety leads you to worry or run away because you’re not in control of life anymore and you feel worse.”

People often move back and forth between too much, just enough, and too little anxiety, and anxiety is contagious, says Rosen: “We communicate our level of anxiety to others because we’re connected to each other,” he says. “Studies show that your blood pressure can go up when you deal with a manger who is disrespectful, unfair, or overly anxious. People are hijacked more and more because of too much anxiety.”

Anxiety is energy, and you can strike the right balance if you know what to look for:

Too Much Anxiety

Some people naturally have too much anxiety, and that’s a problem. “These are the people who need to be right, powerful, in control, and successful,” says Rosen. “They orchestrate everything around them, and are mistrustful or suspicious. They’re scared of inadequacy, failure, being insignificant, or being taken advantage of.”

You have too much anxiety if you tend to expect respect and admiration, are frustrated a lot, question the motives of others, and are overly impatient, says Rosen.

Too Little Anxiety

Too little anxiety isn’t good either. “You put your head in the sand in the face of change,” says Rosen. “You don’t want to take risks. You value status quo and live in a bubble.”

You have too little anxiety if you’re too idealistic and cautious, detaching from all of the change around you. “The world is changing faster than our ability to adapt. We need to learn new things, and can’t stay complacent for long,” he says. “It’s important to allow yourself to stretch and to feel just the right amount of anxiety.”

Good Anxiety

Living with the right amount of anxiety provides just enough tension to drive you forward without causing you to resist, give up, or try to control what happens. “It’s a productive energy,” says Rosen.

The first step is getting comfortable being uncomfortable. “A lot of people think the goal of life is to be happy, but it’s not,” says Rosen. “The goal is to live a full life, and sometimes you’ll have good days and sometimes bad days. Develop the skill of being uncomfortable. Knowing you can and will get through it is important.”

Listen to your body; it speaks to you, says Rosen. “Whether it’s stomach pain or heart palpitations or a stiff neck or back, these are ways the body tells you that you are anxious,” he says.

Ask yourself why you’re anxious. Is it because you’re excited? How you interpret anxiety could be good or bad. If you’re about to give a speech, for example, anxiety is good. Instead of trying to avoid it, understand it. “If you’re not anxious, you’re probably not going to give a great speech,” says Rosen. “And if you’re too anxious, that won’t be a great speech, either.”

When you have too much anxiety, it’s often because you’re telling yourself a story. “For example, ‘If I don’t do a good job I’ll get fired,’ ‘My boss hates me,’ or ‘I’m going to embarrass myself,’” says Rosen. It’s often not the event that causes anxiety; it’s the story we tell ourselves about it.”

When this happens, take a long walk or breathe deeply if you have too much anxiety. Meditation is a force that helps you live in the present moment. “When you meditate, you get a better sense of how your body and mind are reacting,” he says. “Deep breathing creates a direct connection between your breath and reducing stress. You can get a sense of the source of the anxiety, peel back the onion, and find the cause.”

All change happens in the gap between our current reality and desired future, says Rosen. “We have a problem we want to solve or have a goal we want to accomplish,” he says. “In the gap sits our motivation, our engagement, and our anxiety. Anxiety is the energy that moves us across the gap. We need to have enough energy to change. You can’t change or transform yourself unless you allow yourself to feel uncertainty and vulnerability.”

April 25th 2023

How Bad Is It Really to Procrastinate?

By Apr 8, 2023 Medically Reviewed by

There are a lot of reasons people procrastinate, including boredom, frustration, overwhelm and anxiety.

Image Credit: LIVESTRONG.com Creative

How Bad Is It Really? sets the record straight on all the habits and behaviors you’ve heard might be unhealthy.

In This Article

If somebody were to ask whether you’d rather finish a task you’ve been putting off or get a colonoscopy and you hesitate to answer, chances are you’re no stranger to procrastination and the effect it can have on your overall wellbeing.

“Procrastination is an avoidant behavior that involves putting off completing a certain task — usually, because we find it uncomfortable, overwhelming, boring or have other negative associations with the task,” says Victoria Smith, LCSW, a California-based licensed clinical social worker. “By procrastinating, we’re avoiding feeling the discomfort of these negative associations.”

Video of the Day

It’s a habit that can have a range of consequences, including poorly done tasks, lots of stress and an array of negative health outcomes. But when approached from a place of curiosity instead of judgment, getting to know your particular procrastination style can unlock the data you need to break the cycle — and maybe even use procrastinating to your advantage.

Why You Procrastinate in the First Place

“As with many behaviors, the psyche isn’t to blame as much as the brain,” says Taish Malone, PhD, a licensed professional counselor with Mindpath Health. “The limbic system and the prefrontal cortex have been seen as the areas responsible for procrastination.”

The limbic system is a set of brain structures that oversee our behavioral and emotional responses (motivation, reward, responsivity, habits), while the prefrontal cortex acts as our executive assistant, taking care of things like planning, organization and impulse control.

The brains of procrastinators have a larger amygdala than non-procrastinators (the part of the limbic system known for fight-or-flight), according to a small August 2018 study in Psychological Science.

We Recommend

Health

9 Tactics to Help You Overcome Procrastination

Nutrition

The Science Behind Emotional Eating: Why We Do It & How to Stop

Health

This Mental Wellness Resource Is Designed to Help You Manage Your Stress Levels From Your Phone

This suggests that when you’re presented with an unappealing task or a flood of new tasks, the amygdala reacts as if they’re a threat, overruling your prefrontal cortex and ordering you to escape the negative emotions you’re feeling. Cue procrastination.

“If we’re in a situation where we already have a lot on our plate and are perpetually overwhelmed, the brain and body are primed to resist change and newness,” says Dave Rabin, MD, PhD, board-certified psychiatrist, neuroscientist and founder of Apollo Neurosciences.

Procrastination becomes a distorted form of self-preservation where the brain mistakes the instant feeling of relief as a reward. Your brain hits the jackpot each time you put off a task, releasing feel-good chemicals, like dopamine, and reinforcing the belief that avoidance is an adequate and acceptable response to discomfort.

Advertisement

Over time, this feedback loop can become chronic and destructive.

The Emotional Underpinnings of Procrastination

Procrastination has nothing to do with laziness or poor time management, but rather relates to emotion regulation — usually, you want to complete the task you’re avoiding but there are underlying feelings that are holding you back.

These underlying feelings might include:

Boredom. When we’re not mentally stimulated, we’re not receiving any dopamine for beginning or working on a task.

“This means we’re not feeling any immediate reward for the work we’re doing,” Smith says, which can peer pressure us to do something more interesting instead.

Perfectionism. Perfectionism usually comes with subconscious messaging related to not being good enough or a fear of failure, so tasks can feel daunting by default because you’re fighting through feelings of self-doubt on top of the mental load required to complete the task itself.

“It can also feel somewhat protecting to not engage with a task we feel could ultimately prove our fear right — that if we don’t do a perfect job we’re not good enough and other people will see that,” Smith says.

Overwhelm and frustration. “When we’re mentally or physically overloaded, our logical thinking task-oriented brain goes offline and our survival brain kicks in to try and get our basic needs met so our nervous system can recalibrate,” Smith says.

Instead of fight or flight, you freeze, unable to think in a clear, structured manner.

Fear, anxiety and depression. “Fear and anxiety are very powerful emotions that reinforce avoidance because they’re a survival mechanism,” Smith says. “Even though we know a certain task can’t harm us, our bodies may perceive the task as dangerous.”

Meanwhile, depression can trap you in rumination mode (a preoccupation with painful thoughts about the past), the feelings of shame from which may put your social- and self-image into question and encourage task-avoidant behaviors, such as procrastionation, suggests a small July 2022 study published in the Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy.

Sensory overload. If you have autism or ADHD, you might experience attention dysregulation that can make it incredibly challenging to follow through or stay on task. “This may look like procrastination from the outside, but may not be about intentional avoidance at all,” says Peggy Loo, PhD, New York-based licensed psychologist and director of Manhattan Therapy Collective.

The Consequences of Procrastination

One force that powers procrastination is wanting to avoid the feelings, such as boredom or stress, that accompany the task. But this avoidance gives these feelings free reign to collect interest on your insides and make things worse — typically in one or both of these forms:

- Negative emotional consequences — think: feeling more stressed out by the task you’re avoiding

- Situational consequences — the task does not turn out as well as it could have

1. Procrastination Can Become Cyclical

The feelings of inadequacy, anxiety and depression that typically follow avoidance further strengthen the negative associations attached to certain tasks. So the next time there’s a to-do on your list that makes a colonoscopy appealing, you’re even more likely to put it off rather than get it over with.

“This long-term procrastination cycle becomes greater and more encompassing than merely the behavior itself,” Malone says.

But it’s not procrastination itself that’s the problem, so much as our tendency to condemn ourselves for doing it (say, with classic lectures like “suck it up” or “just do it”), the pressure from which only leads to more procrastinating.

2. It May Be Hard on Your Health

Once procrastination becomes a habit, the cumulative effect of the constant turmoil can lead to negative outcomes.

Procrastinating is associated with higher levels of stress, depression and anxiety, along with “reduced satisfaction across life domains, especially regarding work and income,” per a February 2016 study in PLOS One, which looked at several thousand German people, ages 14 to 95. That is, procrastinating has a professional, emotional and financial effect.

Advertisement

And, it can lead to both short- and long-term health issues, including insomnia and digestive concerns. It’s also a “vulnerability factor” with hypertension and cardiovascular disease, per research published in March 2016 in the Journal of Behavioral Medicine. These types of health outcomes could be due to procrastinators being more likely to put off self-care and regular checkups.

Another study followed university students in Sweden, sharing several web-based surveys over the course of a year, looking for associations between procrastination and negative health outcomes. The results, published in January 2023 date in JAMA Network Open, found that “higher levels of procrastination were associated with worse subsequent mental health.” The study also noted that procrastination is associated with poor sleep quality, a lack of physical activity and pain in upper extremities, as well as worse levels of loneliness.

Procrastination vs. Purposeful Delay

Back in 2005, researchers theorized that procrastination comes in two forms: passive (postponing tasks despite the knowledge that doing so will bring on negative consequences) and active (purposefully putting tasks off because you work better under pressure), according to an article in the Journal of Social Psychology.

But procrastinating on a task and deliberately delaying it aren’t the same thing: Procrastination is considered a self-regulation deficit; a voluntary, irrational postponement of tasks despite the blowback postponing them will bring.

“Procrastination isn’t positive for most because it’s not a decision that inherently comes from a place of empowerment, self-control or joy,” Loo says.

Even if a task works out despite leaving it until the last minute, it’s usually a hollow win filled with relief, not pride or satisfaction. This ultimately reinforces the negative beliefs we have about ourselves and our abilities and causes us to engage in the same thought cycle each time we need to complete something important.

Advertisement

“Your identity can even begin to build around the idea that you’re a procrastinator who never gets things done on time and is always stressed out by deadlines — a thought pattern that can become self-fulfilling,” Smith says.

On the flipside, deliberately delaying certain tasks is considered a proactive and thoughtful form of self-regulation.

“The emotional and psychological tone is completely different from procrastination because these actions come from a place of autonomy and thoughtful choice,” Loo says.

Deliberate or purposeful delay isn’t based on an internal need to postpone tasks, but external situational factors requiring you to make rational decisions on how best to prioritize your time according to those demands, per a January 2018 article in Personality and Individual Differences.

“When you don’t need a whole week to do something and put it off until later or decide to call it quits early to clear your mind and reset, yes, you’re technically delaying tasks, but it’s not motivated by avoidance at all,” Loo says. “It’s simply a strategy you know works for you and will aid the overall process.”

Say you’ve hit a wall with your creative project and find yourself deep-cleaning your home. Are you scrubbing away because the thought of facing your project is making you feel angsty? Then you’re probably procrastinating. Or is cleaning your go-to strategy when you know an idea needs to incubate a little longer? That’s purposeful delay in real-time.

So, How Bad Is It Really to Procrastinate?

When you put off tasks out of avoidance and coping-by-not-coping becomes your autopilot, this self-destructive loop can seriously mess with your quality of life, not to mention your long-term health.

Advertisement

But your knee-jerk urge to procrastinate doesn’t come from a bad place: It’s your brain’s attempt at protecting you from the emotional pain and discomfort you’ve attached to certain projects or tasks, such as boredom, perfectionism or overwhelm.

Keeping this in mind the next time you’re tempted to procrastinate can help you work through the uncomfortable feelings that are holding you back instead of avoiding them.

By getting to know your particular procrastination style, you stand a better chance at not only finding effective workarounds, but using putting things off to your advantage in the form of purposeful delay.

Procrastination isn’t the enemy, so much as our not digging deeper into why we’re doing it. So, what’s your need to procrastinate trying to tell you?

Advertisement

Lithium – Brand names: Priadel, Camcolit, Liskonium, Li-Liquid

On this page

- About lithium

- Key facts

- Who can and cannot take lithium

- How and when to take lithium

- Side effects

- How to cope with side effects

- Pregnancy and breastfeeding

- Cautions with other medicines

- Common questions

1. About lithium

Lithium is a type of medicine known as a mood stabiliser.

It’s used to treat mood disorders such as:

- mania (feeling highly excited, overactive or distracted)

- hypo-mania (similar to mania, but less severe)

- regular periods of depression, where treatment with other medicines has not worked

- bipolar disorder, where your mood changes between feeling very high (mania) and very low (depression)

Lithium can also help reduce aggressive or self-harming behaviour.

It comes as regular tablets or slow-release tablets (lithium carbonate). It also comes as a liquid that you swallow (lithium citrate).

Lithium is available on prescription.

2. Key facts

- The most common side effects of lithium are feeling or being sick, diarrhoea, a dry mouth and a metallic taste in the mouth.

- Your doctor will carry out regular blood tests to check how much lithium is in your blood. The results will be recorded in your lithium record book.

- Lithium carbonate is available as regular tablets and modified release (brand names include Priadel, Camcolit and Liskonium).

- Lithium citrate comes as a liquid and common brands include Priadel and Li-Liquid.

3. Who can and cannot take lithium

Lithium can be taken by adults and children over the age of 12 years.

Lithium may not be suitable for some people. Tell your doctor if:

- you have ever had an allergic reaction to lithium or other medicines in the past

- you have heart disease

- you have severe kidney problems

- have an underactive thyroid gland (hypothyroidism) that is not being treated

- you have low levels of sodium in your body – this can happen if you’re dehydrated or if you’re on a low-sodium (low-salt) diet

- you have Addison’s disease, a rare disorder of the adrenal glands

- you have, or someone in your family has, a rare condition called Brugada syndrome – a condition that affects your heart

- you need to have surgery in hospital

- you are trying to get pregnant, are pregnant or breastfeeding

Before prescribing lithium, your doctor will do some blood tests to check your kidney and thyroid are OK. The doctor will also check your weight (and check this throughout your treatment).

If you have a heart condition, the doctor may also do a test that measures the electrical activity of your heart (electrocardiogram).

4. How and when to take lithium

It’s important to take lithium as recommended by your doctor.

There are 2 different types of lithium – lithium carbonate and lithium citrate. It’s important not to change to a different type unless your doctor has recommended it. This is because different types are absorbed differently in the body.

Lithium carbonate comes as regular tablets and slow-release tablets – where the medicine is released slowly over time.

Lithium citrate comes as a liquid. This is usually only prescribed for people who have trouble swallowing tablets .

Doses vary from person to person. Your starting dose will depend on your age, what you’re being treated for and the type of lithium your doctor recommends.

If you have kidney problems your doctor will monitor the level of lithium in your blood even more closely and change your dose if necessary.

You will usually take your lithium once a day, at night. This is because when you have your regular blood test, you need to have it 12 hours after taking your medicine. You can choose when you take your lithium – just try to keep to the same time every day.

How to take it

Swallow tablets whole with a drink of water or juice. Do not chew them. You can take lithium with or without food.

If you’re taking liquid, use the plastic syringe or spoon that comes with your medicine to measure the correct dose. If you do not have one, ask your pharmacist. Do not use a kitchen teaspoon as you will not get the right amount.

Information about your lithium treatment

When you start taking lithium, you will get a lithium treatment pack (usually a purple folder or book) with a record booklet. You need to show your record booklet every time you see your doctor, go to hospital, or collect your prescription.

When you go to the doctor for blood tests, you or your doctor will write in the record booklet:

- your dose of lithium

- your lithium blood levels

- any other blood test results

- your weight

The treatment pack also has a lithium alert card. You’ll need to carry this card with you all the time. It tells healthcare professionals that you’re taking lithium. This can be useful for them to know in an emergency.

Tell your doctor or pharmacist if you’ve lost your treatment pack or did not get one.

Will my dose go up or down?

When you start your treatment you’ll need to have a blood test every week to make sure the level of lithium in your blood is not too high or too low. Your doctor may change your dose depending on the results of your blood test.

Once the doctor is happy you’ll have a blood test every 3 to 6 months to check the level remains steady.

Once you find a dose that suits you, it will usually stay the same – unless your condition changes, or your doctor prescribes another medicine that may interfere with lithium.

Important

Do not stop taking lithium suddenly or change your dose without speaking to your doctor first. It’s important you keep taking it, even if you feel better. If you stop taking it suddenly you could become unwell again very quickly.

What if I’m ill while taking lithium?

Infections and illnesses like colds and flu can make you dehydrated, this can affect the level of lithium in your blood.

Talk to your doctor or pharmacist if you:

- have an illness that causes severe diarrhoea, vomiting, a high temperature or sweating

- have a urinary tract infection (UTI)

- are not eating and drinking much

What if I forget to take it?

If you usually take:

- tablets or slow-release tablets – if it’s less than 6 hours since you were supposed to take your lithium, take it as soon as you remember. If it is more than 6 hours, just skip the missed dose and take your next one at the usual time

- liquid – if you forget to take a dose, just skip the missed dose and take your next one at the usual time

Never take 2 doses at the same time. Never take an extra dose to make up for a forgotten one.

If you forget doses often, it may help to set an alarm to remind you. You could also ask your pharmacist for advice on other ways to help you remember to take your medicine.

What if I take too much?

Immediate action required: Call 999 or go to A&E if:

- you take too much lithium, even if you do not feel any different

This is because very high amounts of lithium can cause problems with your kidneys and other organs. It can cause symptoms such as:

- feeling or being sick

- problems with your eyesight (blurred vision)

- increased need to pee, lack of control over pee or poo

- feeling faint, lightheaded or sleepy

- confusion and blackouts

- shaking or muscle weakness, muscle twitches, jerks or spasms affecting the face, tongue, eyes or neck

If you need to go to A&E, take the lithium packet or the leaflet inside it, plus any remaining medicine, with you.

5. Side effects

If you’re on the right dose and the level of lithium in your blood is right, you may not have any problems taking this medicine.

However, some people find lithium slows down their thinking or makes them feel a bit “numb”.

Common side effects

These are usually mild and go away by themselves. They are more likely to happen when you start taking lithium.

Keep taking the medicine but talk to your doctor or pharmacist if any of the following side effects get worse or do not go away after a few days:

- feeling sick (nausea)

- diarrhoea

- a dry mouth and/or a metallic taste in the mouth

- feeling thirsty and needing to drink more and pee more than usual

- slight shaking of the hands (mild tremor)

- feeling tired or sleepy

- weight gain (this is likely to be very gradual)

Serious side effects:

The level of lithium in your blood is checked regularly. But rarely, you may get side effects because there’s too much lithium in your blood.

Immediate action required: Call 999 or go to A&E now if:

You have 1 or more of these symptoms:

- loss of appetite, feeling or being sick (vomiting)

- problems with your eyesight (blurred vision)

- feeling very thirsty, needing to pee more than normal, and lack of control over pee or poo

- feeling lightheaded or drowsy

- confusion and blackouts

- shaking, muscle weakness, muscle twitches, jerks or spasms affecting the face, tongue, eyes or neck

- difficulty speaking

These are signs of lithium toxicity. Lithium toxicity is an emergency. Stop taking lithium straight away.

How to avoid high lithium levels in your blood

Make sure that you go for the blood tests arranged by your doctor.

It’s important not to reduce your salt intake suddenly. Talk to your doctor if you want to reduce the amount of salt in your diet.

Drink plenty of fluids, especially if you are doing intense exercise or in hot weather when you will sweat more.

Drinking alcohol causes your body to lose water. It’s best not to drink too much as it’s likely to make you dehydrated, especially in hot weather when you will sweat more.

Always tell any doctor or pharmacist that you are taking lithium before you take any new medicines.

Serious allergic reaction:

In rare cases, lithium may cause a serious allergic reaction (anaphylaxis).

Immediate action required: Call 999 or go to A&E if:

- you get a skin rash that may include itchy, red, swollen, blistered or peeling skin

- you’re wheezing

- you get tightness in the chest or throat

- you have trouble breathing or talking

- your mouth, face, lips, tongue or throat start swelling

You could be having a serious allergic reaction and may need immediate treatment in hospital.

These are not all the side effects of lithium. For a full list, see the leaflet inside your medicine packet.

You can report any suspected side effect to the UK safety scheme.

6. How to cope with side effects

What to do about:

- feeling or being sick – take lithium with or after a meal or snack. It may also help if you do not eat rich or spicy food. If you are being sick, take sips of water to avoid dehydration.

- diarrhoea – drink plenty of fluids to avoid dehydration. Signs of dehydration include peeing less than usual or having dark, strong-smelling pee. Do not take any other medicines to treat diarrhoea without speaking to a pharmacist or doctor.

- a dry mouth and/or a metallic taste in the mouth – try sugar-free gum or sweets, or sipping cold drinks. If this does not help, talk to your pharmacist or doctor. Try not to have drinks with a lot of calories in as this might also mean you put on weight.

- slight shaking of the hands (mild tremor) – talk to your doctor if this is bothering you or does not go away after a few days. These symptoms can be a sign that the dose is too high for you. Your doctor may change your dose or recommend taking your medicine at a different time of day.

- feeling tired or sleepy – as your body gets used to lithium, these side effects should wear off. If these symptoms do not get better within a week or two, your doctor may either reduce your dose or increase it more slowly. If that does not work you may need to switch to a different medicine.

- weight gain – try to eat well without increasing your portion sizes so you do not gain too much weight. Regular exercise will help to keep your weight stable and help you feel better.

7. Pregnancy and breastfeeding

Lithium and pregnancy

Lithium is not usually recommended in pregnancy, especially during the first 12 weeks (first trimester) where the risk of problems to the baby is highest. However, you may need to take lithium during pregnancy to remain well. Your doctor may advise you to take it in pregnancy if the benefits of the medicine outweigh the risks.

If you become pregnant while taking lithium, speak to your doctor. It could be dangerous to you and your unborn baby if you stop taking it suddenly. Do not stop taking it or make any change to your dose unless your doctor tells you to.

Talk to your doctor before taking this medicine if you plan to get pregnant, or think you may be pregnant. Your doctor can explain the risks and the benefits and will help you decide which treatment is best for you and your baby.

Lithium and breastfeeding

If your doctor or health visitor says your baby is healthy, you can take lithium while breastfeeding.

Lithium passes into breast milk in small amounts. However, it has been linked with side effects in very few breastfed babies.

It’s important to continue taking lithium to keep you well. Breastfeeding will also benefit both you and your baby.

If you notice that your baby is not feeding as well as usual, or seems unusually sleepy, or if you have any other concerns about your baby, talk to your health visitor or doctor as soon as possible.

Non-urgent advice: Talk to your doctor if you:

- are trying to get pregnant

- are already pregnant

- would like to breastfeed

For more information about how lithium can affect you and your baby during pregnancy, read this leaflet on the Best Use of Medicines in Pregnancy (BUMPS) website.

8. Cautions with other medicines

This are some medicines that may interfere with how lithium works and this can affect the levels of lithium in your blood.

Check with your doctor or pharmacist if you’re taking (or before you start taking):

- tablets that make you pee (diuretics) such as furosemide or bendroflumethiazide

- non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) – used for pain relief and swelling such as aspirin, ibuprofen, celecoxib or diclofenac

- medicines used for heart problems or high blood pressure such as enalapril, lisinopril or ramipril (ACE inhibitors)

- some medicines used for depression such as fluvoxamine, paroxetine or fluoxetine

- antibiotics such as oxytetracycline, metronidazole, co-trimoxazole, trimethoprim

- medicines for epilepsy such as carbamazepine or phenytoin

These are not all the medicines that can affect the way lithium works. Always check with your doctor before you start or stop taking any medicine.

Mixing lithium with herbal remedies or supplements

It’s not possible to say whether complementary medicines and herbal supplements are safe to take with lithium.

They’re not tested in the same way as pharmacy and prescription medicines. They’re generally not tested for the effect they have on other medicines.

Important

For safety, tell your doctor or pharmacist if you’re taking any other medicines, including herbal remedies, vitamins or supplements.

9. Common questions

How does lithium work? How long does it take to work? How will it make me feel? How long will I take it for? What will happen if I stop taking it? Can I take lithium for a long time? Is lithium an antipsychotic? How well does lithium treat depression? Can I drink alcohol with it? Will it affect my contraception? Will it affect my fertility? Is there any food or drink I need to avoid? Can I drive or ride a bike? Can I take lithium with recreational drugs?

Related conditions

Useful resources

Page last reviewed: 18 August 2020

Next review due: 18 August 2023

Support links

- Home

- Health A to Z

- Live Well

- Mental health

- Care and support

- Pregnancy

- NHS services

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- NHS App

April 25th 2023

Eliminating the Human

We are beset by—and immersed in—apps and devices that are quietly reducing the amount of meaningful interaction we have with each other.

- David Byrne

Read when you’ve got time to spare.

Advertisement

More from MIT Technology Review

- Is this AI? We drew you a flowchart to work it out

- A debate between AI experts shows a battle over the technology’s future

- Quantum computing has a hype problem

Advertisement

Illustration by Andy Friedman.

I have a theory that much recent tech development and innovation over the last decade or so has an unspoken overarching agenda. It has been about creating the possibility of a world with less human interaction. This tendency is, I suspect, not a bug—it’s a feature. We might think Amazon was about making books available to us that we couldn’t find locally—and it was, and what a brilliant idea—but maybe it was also just as much about eliminating human contact.

The consumer technology I am talking about doesn’t claim or acknowledge that eliminating the need to deal with humans directly is its primary goal, but it is the outcome in a surprising number of cases. I’m sort of thinking maybe it is the primary goal, even if it was not aimed at consciously. Judging by the evidence, that conclusion seems inescapable.

This then, is the new norm. Most of the tech news we get barraged with is about algorithms, AI, robots, and self-driving cars, all of which fit this pattern. I am not saying that such developments are not efficient and convenient; this is not a judgment. I am simply noticing a pattern and wondering if, in recognizing that pattern, we might realize that it is only one trajectory of many. There are other possible roads we could be going down, and the one we’re on is not inevitable or the only one; it has been (possibly unconsciously) chosen.

I realize I’m making some wild and crazy assumptions and generalizations with this proposal—but I can claim to be, or to have been, in the camp that would identify with the unacknowledged desire to limit human interaction. I grew up happy but also found many social interactions extremely uncomfortable. I often asked myself if there were rules somewhere that I hadn’t been told, rules that would explain it all to me. I still sometimes have social niceties “explained” to me. I’m often happy going to a restaurant alone and reading. I wouldn’t want to have to do that all the time, but I have no problem with it—though I am sometimes aware of looks that say “Poor man, he has no friends.” So I believe I can claim some insight into where this unspoken urge might come from.

Human interaction is often perceived, from an engineer’s mind-set, as complicated, inefficient, noisy, and slow. Part of making something “frictionless” is getting the human part out of the way. The point is not that making a world to accommodate this mind-set is bad, but that when one has as much power over the rest of the world as the tech sector does over folks who might not share that worldview, there is the risk of a strange imbalance. The tech world is predominantly male—very much so. Testosterone combined with a drive to eliminate as much interaction with real humans as possible for the sake of “simplicity and efficiency”—do the math, and there’s the future.

The Evidence

Here are some examples of fairly ubiquitous consumer technologies that allow for less human interaction.

Online ordering and home delivery: Online ordering is hugely convenient. Amazon, FreshDirect, Instacart, etc. have not just cut out interactions at bookstores and checkout lines; they have eliminated all human interaction from these transactions, barring the (often paid) online recommendations.

Digital music: Downloads and streaming—there is no physical store, of course, so there are no snobby, know-it-all clerks to deal with. Whew, you might say. Some services offer algorithmic recommendations, so you don’t even have to discuss music with your friends to know what they like. The service knows what they like, and you can know, too, without actually talking to them. Is the function of music as a kind of social glue and lubricant also being eliminated?

Ride-hailing apps: There is minimal interaction—one doesn’t have to tell the driver the address or the preferred route, or interact at all if one doesn’t want to.

Driverless cars: In one sense, if you’re out with your friends, not having one of you drive means more time to chat. Or drink. Very nice. But driverless tech is also very much aimed at eliminating taxi drivers, truck drivers, delivery drivers, and many others. There are huge advantages to eliminating humans here—theoretically, machines should drive more safely than humans, so there might be fewer accidents and fatalities. The disadvantages include massive job loss. But that’s another subject. What I’m seeing here is the consistent “eliminating the human” pattern.

Automated checkout:Eatsa is a new version of the Automat, a once-popular “restaurant” with no visible staff. My local CVS has been training staff to help us learn to use the checkout machines that will replace them. At the same time, they are training their customers to do the work of the cashiers.

Amazon has been testing stores—even grocery stores!—with automated shopping. They’re called Amazon Go. The idea is that sensors will know what you’ve picked up. You can simply walk out with purchases that will be charged to your account, without any human contact.

AI: AI is often (though not always) better at decision-making than humans. In some areas, we might expect this. For example, AI will suggest the fastest route on a map, accounting for traffic and distance, while we as humans would be prone to taking our tried-and-true route. But some less-expected areas where AI is better than humans are also opening up. It is getting better at spotting melanomas than many doctors, for example. Much routine legal work will soon be done by computer programs, and financial assessments are now being done by machines.

Robot workforce: Factories increasingly have fewer and fewer human workers, which means no personalities to deal with, no agitating for overtime, and no illnesses. Using robots avoids an employer’s need to think about worker’s comp, health care, Social Security, Medicare taxes, and unemployment benefits.

Personal assistants: With improved speech recognition, one can increasingly talk to a machine like Google Home or Amazon Echo rather than a person. Amusing stories abound as the bugs get worked out. A child says, “Alexa, I want a dollhouse” … and lo and behold, the parents find one in their cart.

Big data: Improvements and innovations in crunching massive amounts of data mean that patterns can be recognized in our behavior where they weren’t seen previously. Data seems objective, so we tend to trust it, and we may very well come to trust the gleanings from data crunching more than we do ourselves and our human colleagues and friends.

Video games (and virtual reality): Yes, some online games are interactive. But most are played in a room by one person jacked into the game. The interaction is virtual.

Automated high-speed stock buying and selling: A machine crunching huge amounts of data can spot trends and patterns quickly and act on them faster than a person can.

MOOCS: Online education with no direct teacher interaction.

“Social” media: This is social interaction that isn’t really social. While Facebook and others frequently claim to offer connection, and do offer the appearance of it, the fact is a lot of social media is a simulation of real connection.

What are the effects of less interaction?

Minimizing interaction has some knock-on effects—some of them good, some not. The externalities of efficiency, one might say.

For us as a society, less contact and interaction—real interaction—would seem to lead to less tolerance and understanding of difference, as well as more envy and antagonism. As has been in evidence recently, social media actually increases divisions by amplifying echo effects and allowing us to live in cognitive bubbles. We are fed what we already like or what our similarly inclined friends like (or, more likely now, what someone has paid for us to see in an ad that mimics content). In this way, we actually become less connected—except to those in our group.

Social networks are also a source of unhappiness. A study earlier this year by two social scientists, Holly Shakya at UC San Diego and Nicholas Christakis at Yale, showed that the more people use Facebook, the worse they feel about their lives. While these technologies claim to connect us, then, the surely unintended effect is that they also drive us apart and make us sad and envious.

I’m not saying that many of these tools, apps, and other technologies are not hugely convenient, clever, and efficient. I use many of them myself. But in a sense, they run counter to who we are as human beings.

We have evolved as social creatures, and our ability to cooperate is one of the big factors in our success. I would argue that social interaction and cooperation, the kind that makes us who we are, is something our tools can augment but not replace.

When interaction becomes a strange and unfamiliar thing, then we will have changed who and what we are as a species. Often our rational thinking convinces us that much of our interaction can be reduced to a series of logical decisions—but we are not even aware of many of the layers and subtleties of those interactions. As behavioral economists will tell us, we don’t behave rationally, even though we think we do. And Bayesians will tell us that interaction is how we revise our picture of what is going on and what will happen next.

I’d argue there is a danger to democracy as well. Less interaction, even casual interaction, means one can live in a tribal bubble—and we know where that leads.

Is it possible that less human interaction might save us?

Humans are capricious, erratic, emotional, irrational, and biased in what sometimes seem like counterproductive ways. It often seems that our quick-thinking and selfish nature will be our downfall. There are, it would seem, lots of reasons why getting humans out of the equation in many aspects of life might be a good thing.

But I’d argue that while our various irrational tendencies might seem like liabilities, many of those attributes actually work in our favor. Many of our emotional responses have evolved over millennia, and they are based on the probability that they will, more likely than not, offer the best way to deal with a situation.

What are we?

Antonio Damasio, a neuroscientist at USC wrote about a patient he called Elliot, who had damage to his frontal lobe that made him unemotional. In all other respects he was fine—intelligent, healthy—but emotionally he was Spock. Elliot couldn’t make decisions. He’d waffle endlessly over details. Damasio concluded that although we think decision-making is rational and machinelike, it’s our emotions that enable us to actually decide.

With humans being somewhat unpredictable (well, until an algorithm completely removes that illusion), we get the benefit of surprises, happy accidents, and unexpected connections and intuitions. Interaction, cooperation, and collaboration with others multiplies those opportunities.

We’re a social species—we benefit from passing discoveries on, and we benefit from our tendency to cooperate to achieve what we cannot alone. In his book Sapiens, Yuval Harari claims this is what allowed us to be so successful. He also claims that this cooperation was often facilitated by an ability to believe in “fictions” such as nations, money, religions, and legal institutions. Machines don’t believe in fictions—or not yet, anyway. That’s not to say they won’t surpass us, but if machines are designed to be mainly self-interested, they may hit a roadblock. And in the meantime, if less human interaction enables us to forget how to cooperate, then we lose our advantage.

Our random accidents and odd behaviors are fun—they make life enjoyable. I’m wondering what we’re left with when there are fewer and fewer human interactions. Remove humans from the equation, and we are less complete as people and as a society.

“We” do not exist as isolated individuals. We, as individuals, are inhabitants of networks; we are relationships. That is how we prosper and thrive.

David Byrne is a musician and artist who lives in New York City. His most recent book is called How Music Works. A version of this piece originally appeared on his website, davidbyrne.com.

Copyright © 2017. All rights reserved MIT Technology Review; www.technologyreview.com.

April 22nd 2023

The Day Dostoyevsky Discovered the Meaning of Life in a Dream

“And it is so simple… You will instantly find how to live.”

The Marginalian (formerly Brain Pickings)

- Maria Popova

One November night in the 1870s, legendary Russian writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky (November 11, 1821–February 9, 1881) discovered the meaning of life in a dream — or, at least, the protagonist in his final short story did. The piece, which first appeared in the altogether revelatory A Writer’s Diary (public library) under the title “The Dream of a Queer Fellow” and was later published separately as The Dream of a Ridiculous Man, explores themes similar to those in Dostoyevsky’s 1864 novel Notes from the Underground, considered the first true existential novel. True to Stephen King’s assertion that “good fiction is the truth inside the lie,” the story sheds light on Dostoyevsky’s personal spiritual and philosophical bents with extraordinary clarity — perhaps more so than any of his other published works. The contemplation at its heart falls somewhere between Tolstoy’s tussle with the meaning of life and Philip K. Dick’s hallucinatory exegesis.

The story begins with the narrator wandering the streets of St. Petersburg on “a gloomy night, the gloomiest night you can conceive,” dwelling on how others have ridiculed him all his life and slipping into nihilism with the “terrible anguish” of believing that nothing matters. He peers into the glum sky, gazes at a lone little star, and contemplates suicide; two months earlier, despite his destitution, he had bought an “excellent revolver” with the same intention, but the gun had remained in his drawer since. Suddenly, as he is staring at the star, a little girl of about eight, wearing ragged clothes and clearly in distress, grabs him by the arm and inarticulately begs his help. But the protagonist, disenchanted with life, shoos her away and returns to the squalid room he shares with a drunken old captain, furnished with “a sofa covered in American cloth, a table with some books, two chairs and an easy-chair, old, incredibly old, but still an easy-chair.”

As he sinks into the easy-chair to think about ending his life, he finds himself haunted by the image of the little girl, leading him to question his nihilistic disposition. Dostoyevsky writes:

I knew for certain that I would shoot myself that night, but how long I would sit by the table — that I did not know. I should certainly have shot myself, but for that little girl.

You see: though it was all the same to me, I felt pain, for instance. If any one were to strike me, I should feel pain. Exactly the same in the moral sense: if anything very pitiful happened, I would feel pity, just as I did before everything in life became all the same to me. I had felt pity just before: surely, I would have helped a child without fail. Why did I not help the little girl, then? It was because of an idea that came into my mind then. When she was pulling at me and calling to me, suddenly a question arose before me, which I could not answer. The question was an idle one; but it made me angry. I was angry because of my conclusion, that if I had already made up my mind that I would put an end to myself to-night, then now more than ever before everything in the world should be all the same to me. Why was it that I felt it was not all the same to me, and pitied the little girl? I remember I pitied her very much: so much that I felt a pain that was even strange and incredible in my situation…