March 28th 2024

There is mounting evidence that starting a business reduces stress–and persistent myths that are stopping employees from taking the plunge

March 25, 2024 at 10:41

In 1989, a 39-year-old executive found herself at a crossroads. After 17 arduous years of climbing the corporate ladder at Vogue, she lost the editor-in-chief position to a rival, Anna Wintour. One day, while struggling to find the right gown for her upcoming wedding, she spotted a business opportunity: designing dresses for others. Hesitant, she wasn’t sure she’d make it: “Maybe it’s just too late for me,” the executive wondered. Still, she took the plunge, and one year later, she opened a boutique at New York City’s Carlyle Hotel.

Fast forward to 2024, and that executive is Vera Wang, one of the most successful fashion designers in the world, with a net worth of over $650 million. It’s easy to marvel at Wang’s financial success. But as new research reveals, the real reward of starting a business extends well beyond money–it also means lower stress, better health, and a more meaningful career.

The burnout that drives successful people to leave corporate America has only intensified in recent years. During the height of the pandemic, Gallup recorded record-setting stress levels. It would be easy to dismiss this figure as an unavoidable byproduct of COVID-19, except for one excruciating detail: We’re just as stressed out today.

Why entrepreneurs report less stress than the average worker

As someone who has helped thousands of entrepreneurs, I know firsthand the benefits of–and misconceptions about–taking employment into one’s own hands and starting a business. After a year filled with record-setting layoffs, return-to-work mandates, and the looming threat of AI, it’s time to take research on worker welfare seriously, and debunk the myths that keep employees from healthier, more satisfying, and less stressful lives.

In recent years, a new wave of peer-reviewed research indicates that launching a business can dramatically reduce stress and improve physical and mental health. That revelation first gained traction with a groundbreaking paper published in the Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. In it, researchers compared a nationally representative sample of employees and entrepreneurs on various health factors, including blood pressure, physician visits, physical and mental illness, and overall well-being. The results overwhelmingly favored entrepreneurs, who evidenced significantly lower blood pressure and hypertension rates, fewer hospital visits, and reduced incidence of physical and mental illnesses.

How can starting a business, which many justifiably consider a massive and nerve-wracking undertaking, possibly reduce stress?

A 2020 study offers important clues as to why entrepreneurs report less stress than the average American. Economists at Colorado State University and Florida Atlantic University concluded that founding a business fosters a greater sense of purpose as entrepreneurs experience more autonomy and competence at work.

And although we’ve been taught that being an employee is the safer financial path, a 2022 JP Morgan report indicates that the median self-employed household has a net worth more than four times greater than the median worker. Counterintuitively, launching a business yields greater financial stability than working for an employer.

March 18th 2024

Pilot Fatigue

Pilot fatigue is in the spotlight this week, after the news that one Indonesian flight had two sleeping pilots at its helm. But military organisations have been grappling with this problem for decades – and they have a surprising solution.

The intriguing tablets were discovered in a Nazi’s pocket. The pilot had been shot down over Britain in a bombing raid during World War Two – along with the remains of his methamphetamine supply. At the time, this was the Luftwaffe’s favourite pick-me-up for fatigued airmen, known as “pilot’s salt” for its liberal application. But though the allied forces suspected this, they didn’t know for sure.

The pharmacological souvenirs were promptly shipped off for testing, and soon the British were working on their own version. The resulting stimulant was widely distributed, and fuelled hundreds of late-night missions across Europe. But this was just the beginning. A related drug, dextroamphetamine, again became popular during the Gulf War in 1990-91, when it was taken by the majority of fighter pilots involved in the initial bombardments on Iraqi forces in Kuwait. Today this pill is still in use by US military aircrews. They use it to solve the same problem, pilot fatigue, which can creep up on aviators during long missions and compromise their safety.

But there’s a catch. Amphetamines can be highly addictive – and even in the 1940s they were widely abused. So, in recent years, military organisations have been on the hunt for another option.

Enter modafinil, a stimulant originally developed for the treatment of narcolepsy and excessive daytime drowsiness in the 1970s. It didn’t take long for people to discover that, while the drug can help to prevent people from falling asleep, it can also have powerful effects. The medication has been shown to improve spatial planning, pattern recognition, and working memory, as well as boosting overall cognitive performance, alertness, and vigilance in situations of extreme fatigue.

Modafinil has its own flaws. Side effects can include sweating, pounding headaches, and even hallucinations. Depite these risks, in certain circumstances it can be a formidable aid for those who need to stay awake. In one early study the drug kept people alert for up to 64 hours of activity, and its effects have been compared to drinking 20 cups of coffee. How does it work? And why is it used?

A powerful stimulant

In the world of fighter pilots, there are two kinds of drugs: go-pills and no-go pills. The former are stimulants, and increase the activity of the central nervous system – one reason amphetamines are sometimes known by the street name “speed”. The latter are depressant substances, which slow down the transmission of messages between the brain and the body. In situations where the timing of alertness and sleep is critical, air forces sometimes use these medications to command the body into cooperation. So, along with an arsenal of sleep aids, this is where modafinil comes in.

Modafinil is already widely available – approved for use by air forces in Singapore, India, France, the Netherlands, and the United States. Meanwhile, an investigation by the Guardian newspaper in the UK revealed that a substantial cache of the drug had been purchased by the UK Ministry of Defence ahead of the beginning of the war in Afghanistan in 2001. Another order had been secured in 2002, before the invasion of Iraq, Though a defence research agency conducted experiments with the pills, they were reportedly not used on combat personnel.

During the Gulf War, Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm involved intense initial bombardments, and many pilots took amphetamines to stay alert (Credit: Getty Images)

In fact, chemically enhanced airmen have been involved in hundreds of military operations over the last decade alone.

As they flit about the sky, fighter pilots often have just a few seconds to observe their surroundings and decide how to react to threats, so tiredness can easily be fatal. But oddly, intense flights involving serious warfare or manoeuvres are not the only ones where pilots tend to struggle with lack of sleep – in fact, boring flights come with their own challenges.

“If you’re just observing, five hours feels way longer than when you’re doing a combat mission,” says Yara Wingelaar-Jagt, a lieutenant colonel and head of the aerospace medicine department at the Dutch Ministry of Defence in Soesterberg, the Netherlands. In fast-paced situations, the body produces its own stimulant drug, adrenaline, which increases alertness and reduces feelings of fatigue – at least in the short-term. On the other hand, less engaging missions might lead to boredom, which could emphasise the impact of exhaustion.

The commercial airline pilots who fell asleep

In January 2023, two pilots boarded an Airbus A320 with 153 passengers and crew onboard. One asked his co-pilot to take over the control of the plane while he napped, and the other agreed. But it didn’t go to plan. In March 2024, a report by Indonesia’s National Transportation Safety Committee (KNKT) revealed that the fight from South East Sulawesi to Jakarta had effectively been pilot-less for 28 minutes, after both pilots fell asleep simultaneously. The incident has prompted a national inquiry, and highlighted the issue of pilot fatigue in commercial operations.

“A couple of years ago, when our test pilots had completed a new mission, they complained that the then-current fatigue countermeasure, caffeine, was not sufficient,” says Wingelaar-Jagt. “They wanted something else to help them stay awake during the flight.”

To find out if modafinil might be the answer, Wingelaar-Jagt and colleagues conducted a randomised controlled trial. Volunteers at the Royal Netherlands Air Force were kept up for 17 hours and then either offered a dose of modafinil, caffeine or a placebo. Next, they were assessed for their vigilance and sleepiness. The researchers found that both caffeine and modafinil were effective, though the latter worked for longer.

Even after an entire night without sleep, some people who took the drug felt that they could probably keep going for another day, she says. “Because of the modafinil, they felt definitely less fatigued and felt more alert,” says Wingelaar-Jagt

It’s not just pilots who may suffer from the effects of sleep deprivation in a military context. To complete certain operations successfully, the crew, particularly on helicopters, might also include a door gunner – someone whose job it is to direct and fire weapons – as well as loadmaster to load and unload important cargo. On the ground, there will always be air traffic controllers to help pilots take off and land.

A tricky dilemma

Of course, there are serious ethical and legal implications involved with offering stimulants like modafinil to military personnel. What would happen if someone refused to take a drug deemed necessary for the success of a mission?

The methamphetamines taken by German Luftwaffe pilots during WW2 were extremely similar to the highly addictive, illegal drug crystal meth (Credit: Getty Images)

One study on the potential challenges of allowing stimulants in the Canadian armed forces highlights the following contradiction: while it’s not legal to force someone to take a medication in Canada, it is a legal requirement for military personnel to perform “any functions that they may be required to perform” any time, day or night. If it was deemed necessary for someone to take modafinil for operational reasons, they could refuse, but they don’t have the right to fail as a result. And the stakes may be high: falling asleep on an aircraft could lead to widespread casualties, including civilians, in addition to the loss of planes costing tens of millions and the failure of an important mission.

“For us [at the Royal Netherlands Air Force], it’s very important that we do not want to force someone to take modafinil,” says Wingelaar-Jagt. “It’s a countermeasure against fatigue, but it does not take away the fatigue itself. So most importantly, in order to combat fatigue, you still have to emphasise on rostering, scheduling,” she says.

Wingelaar-Jagt explains that it’s important to question whether each night-time flight is truly necessary, though occasionally they can’t be avoided. “It might be better for a battleplan, or it might be necessary because of a threat,” she says.

And modafinil is not a perfect drug. Like all medications, it comes with side-effects, and these can be mental as well as physical. Several studies have found that the medication can lead to people becoming overconfident in their judgments – something that could be fatal when flying at speeds that can easily reach 1,190 mph (1,915km/h).

The Nazis had similar problems when medicating their air force during WW2. In all, they distributed some 35 million methamphetamine pills to military personnel in the spring and summer of 1940 alone. However, it soon transpired that the drug-addled pilots had poor judgement, often believing that their performance was good – even when it was in fact terrible. Eventually the authorities became concerned that the drugs, which were sold under the brand name Pervitin, might actually cause accidents.

And like amphetamines, modafinil can be addictive – though much less potent. It is also susceptible to abuse. The medication became a popular smart drug in the 2000s, used by students hoping to stay up all night to study, or time-strapped workers hoping to get ahead.

The amphetamines used by military pilots in the last few decades are significantly milder than those taken during WW2, though they can be highly addictive (Credit: Getty Images)

A very different proposition

But what does all this mean for commercial pilots? After all, though the lengths of their shifts are often more heavily regulated than those of military pilots, they might spend 1,000 hours each year among the clouds, striving against the fog of jet lag and extreme fatigue. One 2023 survey of 6,900 pilots working in Europe found that 72.9% felt they did not have sufficient rest to recover between shifts – while three quarters had experienced a microsleep while on duty in the last month. (Read more from BBC Future about the naps that only last seconds.)

In Wingelaar-Jagt’s opinion, though the benefits of modafinil for military pilots might also apply to commercial aviation, arguably they shouldn’t. “I believe for commercial aviation we have to be sceptical about what we ask of our pilots and our society. Do we really need our commercial pilots to fly through the night to get us to our city trip, or do we need to accept that even humans have their limits and respect the universal need for sleep?” she says.

Instead, Wingelaar-Jagt suggests that modafinil might have some value for other professions with long hours, such as emergency care or firefighting. “For those lines of work it is beyond a doubt that they need to be able perform optimal even in times when one is already fatigued,” she says.

One study found that doctors who had been up all night performed better on a range of tasks that might be relevant to their duties when they had taken modafinil – they were more efficient at solving problems involving planning and working memory, and less impulsive decision-makers. However, as with military pilots, there are ethical snags – particularly the concern that medical professionals might be pressured into using them.

—

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can’t-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.

March 8th 2024

When a young woman earning her Ph.D. in biostatistics came to see psychiatrist Michael Gandal with symptoms of psychosis, she became the fifth person in her immediate family to be diagnosed with a neurodevelopmental or psychiatric condition—in her case, schizophrenia. One of her brothers is autistic and another has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and Tourette syndrome. Their mother has anxiety and depression and their father has depression.

Gandal has seen this pattern before. “If one person, say, has a diagnosis of schizophrenia in their family, not only are other people in the extended family more likely to have diagnosis of schizophrenia but they are also more likely to have a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, autism or major depression,” Gandal says. This propensity runs in families.

The latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the mental health field’s diagnostic standard, describes nearly 300 distinct mental disorders, each with its own characteristic symptoms. Yet increasing evidence suggests the lines between them are blurry at best. Individuals with mental disorders often have symptoms of many different conditions, either simultaneously or at different times in their lives. What’s more, as the family patterns suggest, the genes linked with these conditions overlap. “Everything is genetically correlated,” says Robert Plomin, a behavioral geneticist at King’s College London. “The same genes are affecting a lot of different disorders.”

In fact, it’s difficult to find specific causes of any sort, be they genetic or environmental, for individual psychiatric disorders, says Duke University psychologist Avshalom Caspi. The same is not true of most neurological disorders, such as epilepsy or multiple sclerosis. Those conditions seem to have a distinct genetic and biological origin, in contrast to the “deeply interconnected nature for psychiatric disorders,” according to findings published in 2018.

Put another way, scientists say there exists a propensity to develop any of a range of psychiatric problems. They call this predisposition the general psychopathology factor, or p factor. This shared tendency is not a minor contributor to the extent to which someone develops symptoms of mental illness. In fact, it explains about 40 percent of the risk.

The concept is akin to general cognitive ability, or g, which predicts scores on tests of skills such as spatial ability or verbal fluency. And it suggests that what joins mental health conditions is at least as important as what divides them. The concept of p, Caspi says, “is almost a clarion call for focusing on what is common rather than being preoccupied with what is distinct.”

A few researchers are calling for the erasure of hard boundaries between psychiatric conditions, which could have dramatic consequences for both the diagnosis and treatment of these disorders. “I think this will be the end of diagnostic classification schemes,” Plomin says.

Although that is not likely to happen soon, given that doctors and insurers rely on the DSM’s diagnostic codes, researchers have proposed alternative schemes that are more in line with the concept of p. At the very least, some experts say, mental health research, including clinical trials of treatments, should break free of its DSM silos and encompass multiple diagnoses. “We should be looking at psychopathology without the blinkers of the DSM,” says Patrick McGorry, a psychiatrist and professor of youth mental health at the University of Melbourne in Australia.

Curated by Our Editors

- Psychiatry’s “Bible” Gets an OverhaulFerris Jabr

- Doctoring the Mind: Is Our Current Treatment of Mental Illness Really Any Good?Nicole Branan & Allison Bond

- Depression’s Evolutionary RootsPaul W. Andrews & J. Anderson Thomson Jr.

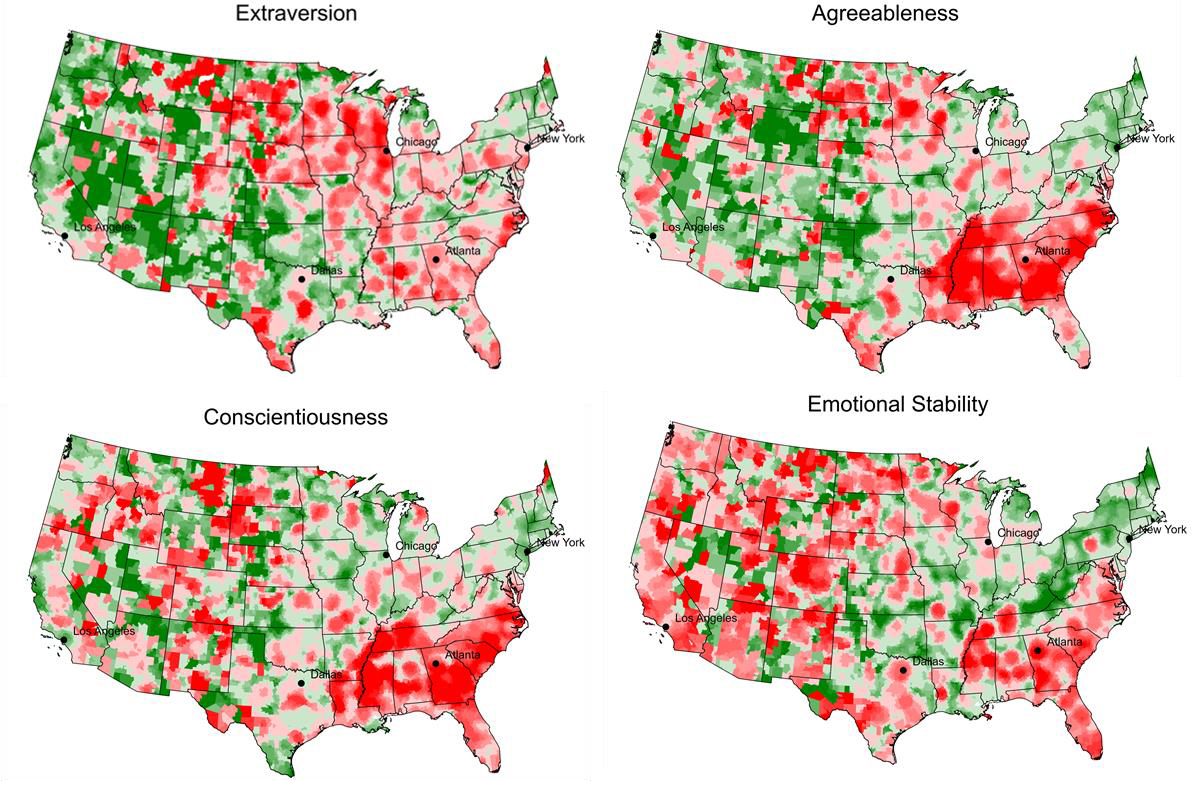

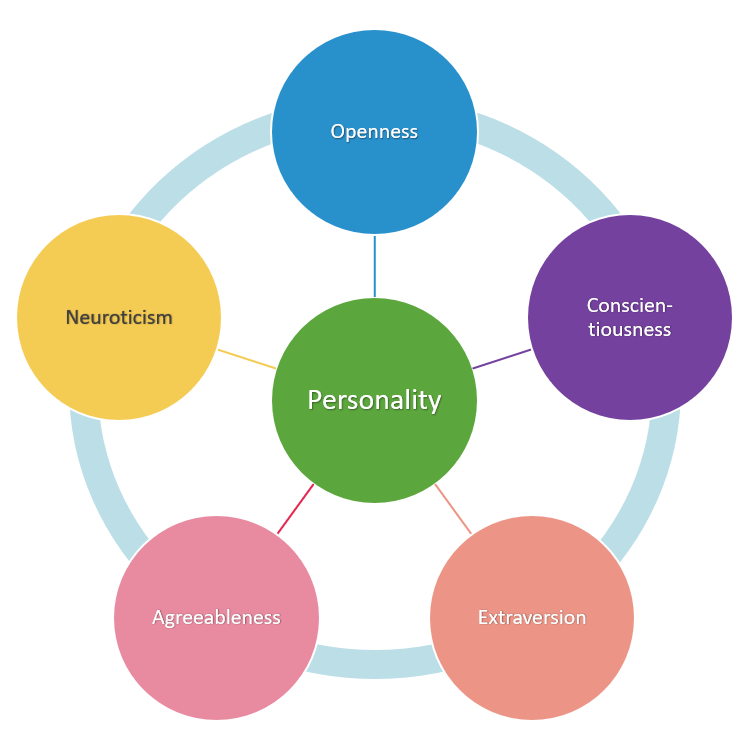

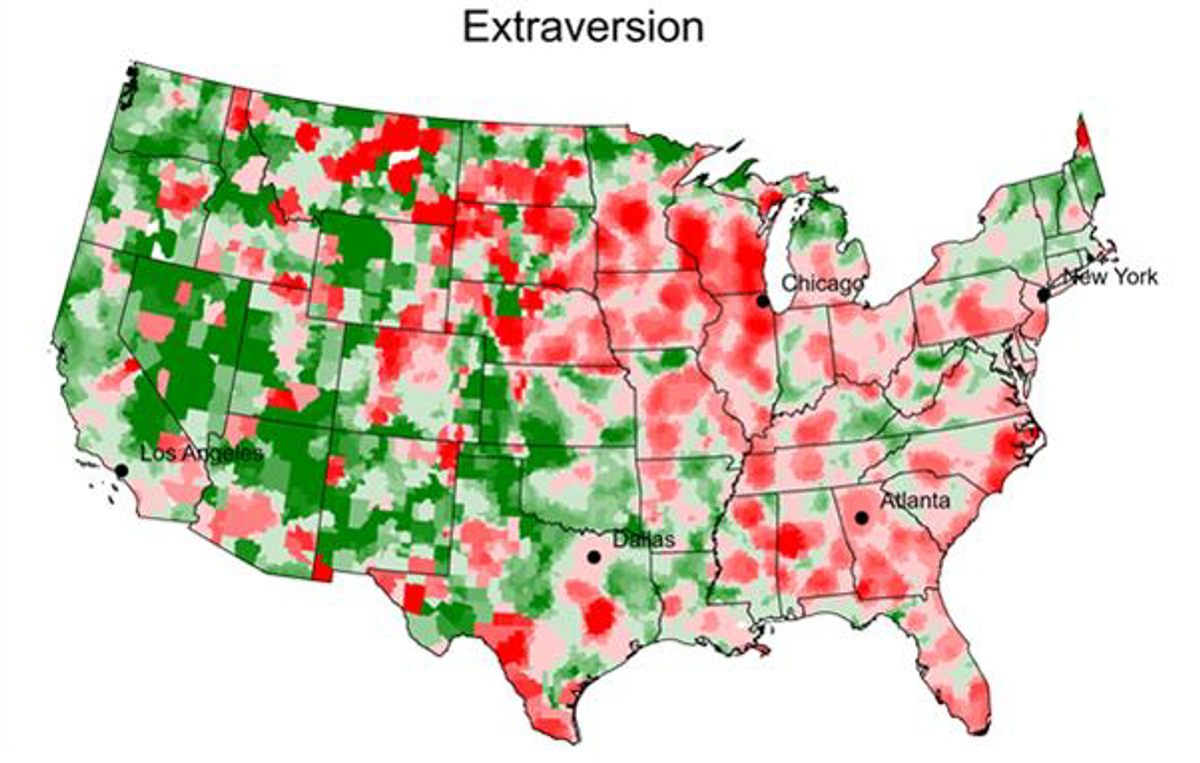

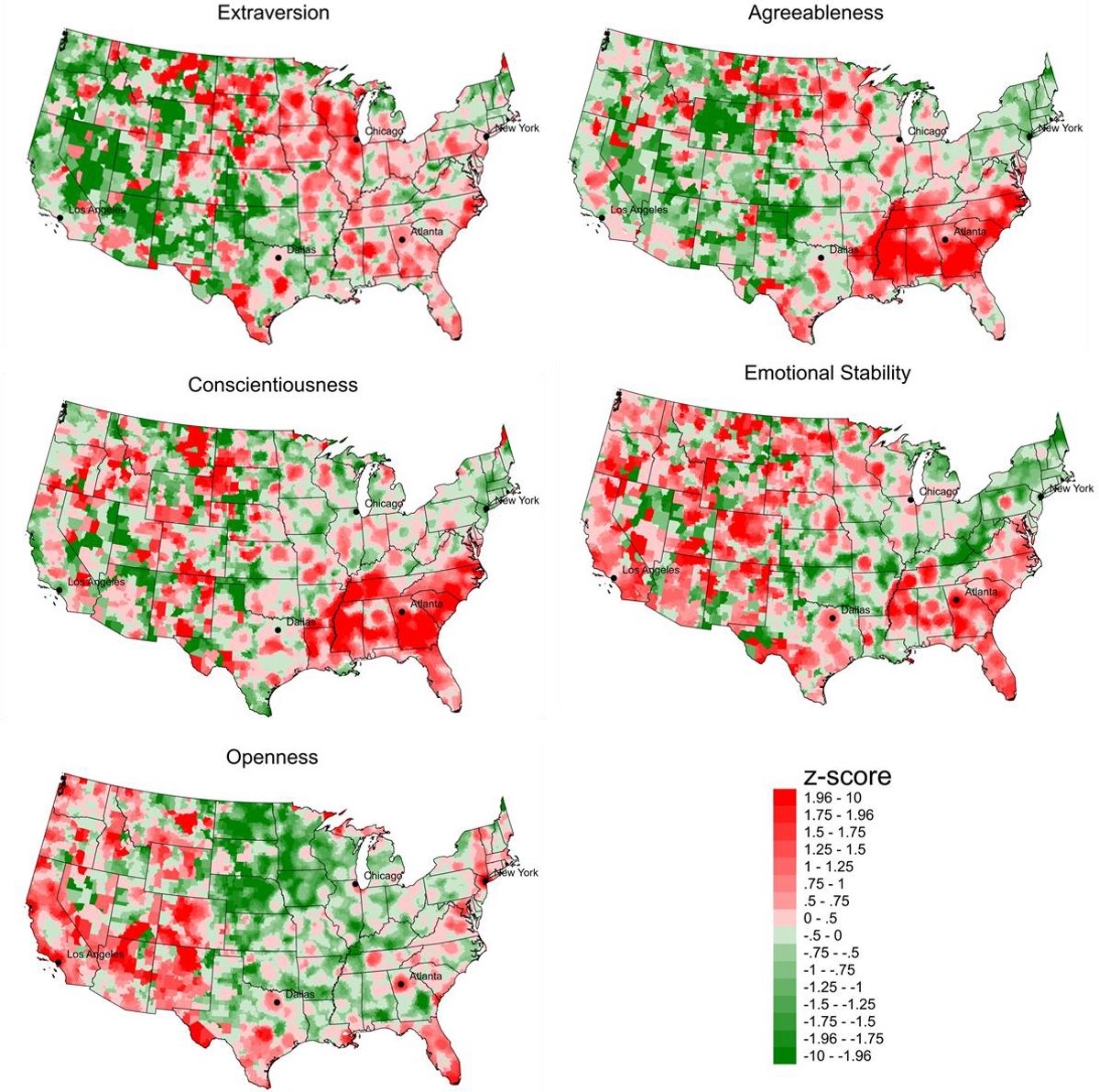

- Personality Tests Aren’t All the Same. Some Work Better Than OthersSeth Stephens-Davidowitz & Spencer Greenberg

Some scientists have already cast off the DSM’s blinkers. Their efforts to uncover the genes or brain signatures that may underlie the p factor could inch us closer to a deeper understanding of psychiatric illness. “If you can find a biology that the p factor is working through, then in theory, if you could find ways to target the biology,” the resulting treatment would likely be effective for many psychiatric disorders, Gandal says.

Others argue that the p factor does not necessarily reflect a common cause of psychiatric illness. It may instead represent qualities present in different types of mental illness, akin to a symptom such as fever that emerges in response to various viral illnesses, says Roman Kotov, a clinical psychologist and a professor of psychiatry at Stony Brook University.

And the pursuit of a p factor was sharply criticized in a recent article in the journal Nature Reviews Psychology. The paper’s authors questioned the statistical model used to justify the p factor’s validity. This model, they contend, will tend to confirm the presence of a p factor regardless of whether one exists. “It’s very clear at this point that the evidence people are using to claim that they’ve found a p factor is not sufficient to prove its existence,” says lead author Ashley Watts, a psychologist at Vanderbilt University.

Yet the data backing the DSM’s version of reality is at least as flimsy, experts say. The disorders codified in the manual grew out of patterns of symptoms that doctors noticed in their patients. In a 1943 paper, for example, psychiatrist Leo Kanner outlined the criteria for autism based on the traits he observed in 11 children. But it is hard to prove that a condition defined by difficulties with social interaction combined with repetitive and restricted behaviors really exists. “On what basis do we say there’s a syndrome, do those things go together?” Plomin says. “They don’t go together. The components of autism are less genetically correlated with each other than major disorders are correlated with each other.”

More evidence that the DSM’s boundaries are soft, if not fictitious, has to do with the observation that many, if not most, people with a mental illness—as many as 82 percent of those with schizophrenia, recent data suggest—exhibit symptoms that cross those boundaries, sometimes leading to multiple diagnoses. For instance, individuals with depression often have anxiety, and those with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are likely to have a substance use disorder.

Features of mental illness that span classic diagnoses may be most common in the earliest stages of distress, McGorry says. “It’s kind of an array of anxiety, depression, maybe a few little warning signs of psychosis in a significant proportion, a bit of mood instability in others, drug and alcohol [misuse] in a subset,” he says. “If you hadn’t ever read a DSM, it wouldn’t naturally occur to you” that the manual’s method of classifying disorders would be useful.

Yet another sign of the arbitrary quality of the DSM’s designations has to do with the way a diagnosis can shift over time. In one longitudinal study, scientists tracked the mental health of roughly 1,000 people born in Dunedin, New Zealand, in 1972 and 1973. In a 2020 report of the participants at age 45, Caspi and his colleagues found that people who are diagnosed with a mental health disorder often see that diagnosis changed some years later. A substance use disorder may remit and give way to depression, for example, only to later return as depression is replaced by severe anxiety, Caspi says.

A general predisposition to mental illness—what many see as the essence of the p factor—could explain the fluidity in diagnoses. Evidence from genetics supports this view. Studies show considerable genetic overlap among diagnoses made based on the DSM.

In a genome-wide association study (GWAS) of a psychiatric disorder, researchers compare the genomes of tens or even hundreds of thousands of people who have that specific mental health condition with those of an equal number of individuals without such a disorder. In so doing, they link small changes in DNA to the condition being studied. The first such studies of psychiatric disorders, published about 15 years ago, showed that many of the specific versions of genes associated with bipolar disorder were the same as those associated with schizophrenia. “These things that we think are distinct, most notably bipolar and schizophrenia, are not at all distinct,” Plomin says. “That was kind of mind-boggling.”

February 22nd 2024

Why we fear uncertainty — and why we shouldn’t

Expert knowledge is useful for problem-solving. So is adapting to new challenges.

By Sean Illing@seanillingsean.illing@vox.com Feb 17, 2024, 8:00am EST

Share this story

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/73146327/GettyImages_1272116889.0.jpg)

One of the things that human beings seem to fear is uncertainty. Most of us like to know things, and when we don’t know things, we get uncomfortable. And when we’re forced to face the unknown, our response is often to retreat into old ideas and routines.

Why is that? What’s so unnerving about ambiguity?

Maggie Jackson is a journalist and the author of a delightful new book called Uncertain: The Wisdom and Wonder of Being Unsure. It makes a great case for uncertainty as a philosophical virtue, but it also uses the best research we have to explain why embracing uncertainty primes us for learning and can improve our overall mental health.

So I invited her onto The Gray Area recently to talk about what she’s learned and how to think about it in our practical lives. Below is an excerpt of our conversation, edited for length and clarity. As always, there’s much more in the full podcast, so listen to and follow The Gray Area on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, or wherever you find podcasts. New episodes drop every Monday.

Sean Illing

How did you come to this topic?

Maggie Jackson

Reluctantly, to be honest.

This is my third book. I’ve been writing about topics that are right under our noses, that we don’t understand or that we deeply misunderstand. The first book was about the nature of home in the digital age. The second book was about distraction, but particularly attention, which very few people could define.

And then finally I started writing a book about thinking in the digital age and the first chapter was about uncertainty. And not only did I discover uncertainty hadn’t really been studied or acknowledged, but there’s now this new attention to it. Lots and lots of new research findings, even in psychology. But I was still reluctant. Like many people, I had this idea that it was just something to eradicate, that uncertainty is something to get beyond, and shut it down as fast as possible.

Sean Illing

So what’s beneath our near-universal fear of the unknown?

Maggie Jackson

As human beings, we dislike uncertainty for a real reason. We need and want answers. And this unsettling feeling we have is our innate way of signaling that we’re not in the routine anymore. And so it’s really important to understand, in some ways, how rare and wonderful uncertainty is.

At the same time, we also need routine and familiarity. Most of life is what scientists call predictive processing. That is, we’re constantly making assumptions and predicting. You just don’t think that your driveway is going to be in a different place when you get home tonight. You can expect that you know how to tie your shoelaces when you get up in the morning. We’re enmeshed in this incredible world of our assumptions. It’s so human, and so natural, to stick to routine and to have that comfort. If everything was always new, if we had to keep learning everything again, we’d be in real trouble.

But neuroscientists are beginning to unpack what happens in the brain when we deal with the stress of uncertainty. The uncertainty of the moment, the realization that you don’t know, that you’ve reached the limits of your knowledge, instigate a number of neural changes. Your focus broadens, and your brain becomes more receptive to new data, and your working memory is bolstered. Which is why facing uncertainty is a kind of wakefulness. In fact, Joseph Kable of the University of Pennsylvania said to me, “That’s the moment when your brain is telling itself there’s something to be learned here.”

Sean Illing

We can think of uncertainty as a precursor to good thinking, and I suppose it is. But that makes it sound a little too much like a passive state, as opposed to an active orientation to the world. Do you think of uncertainty as something closer to a disposition?

Maggie Jackson

Uncertainty is definitively a disposition. We each have our personal comfort zone when it come to uncertainty, and our impression is that uncertainty is static, that it’s synonymous with paralysis. But when you take up that opportunity to learn the good stress that uncertainty offers you, you actually slow down — there are less snap judgments, you’re not racing to an answer. Uncertainty, in other words, involves a process, and that’s really, really important.

The way we think of experts is a good example. We venerate the swaggering kind of expert who knows what to do, whose know-how was developed over the so-called 10,000 hours of experience. But that type of expertise needs updating. That type of expert’s knowledge tends to fall short when facing new, unpredictable, ambiguous problems — the kind of problems that involve or demand uncertainty.

So years of experience are actually only weakly correlated with skill and accuracy in medicine and finance. People who are typical routine experts fall into something called carryover mode, where they’re constantly applying their old knowledge, the old heuristic shortcut solutions, to new situations, and that’s when they fail. Adaptive experts actually explore a problem.

Sean Illing

The idea that not knowing can be a strength does intuitively seem like a contradiction.

Maggie Jackson

Knowledge is incredibly important. It’s the foundation and the groundwork.

But at the same time, we need to update our understanding of knowledge and understand that knowledge is mutable and dynamic. People who are intolerant of uncertainty think of knowledge as something like a rock that we are there to hold and defend, whereas people who are more tolerant of uncertainty are more likely to be curious, flexible thinkers. I like to say that they treat knowledge as a tapestry whose mutability is its very strength.

Sean Illing

I doubt anyone would argue that ignorance is a virtue, but openness to revising our beliefs is definitely a virtue, and that’s the distinction here.

Maggie Jackson

It’s really important to note that uncertainty is not ignorance. Ignorance is the blank slate.

In child development, there’s an expression called the zone of proximal development, which is usually used as a shorthand for scaffolding. That’s the place where a child is pushing beyond their usual knowledge, they’re trying something complex and new and the parent might scaffold a little bit and help only where necessary, but letting them do the work of expanding their limits.

But that’s something we do throughout our whole lives. That zone of proximal development, as one scientist told me, is the green bud on the tree. That’s where we want to be. That’s where we thrive as thinkers and as people.

Sean Illing

When does uncertainty become paralyzing?

Maggie Jackson

Forward motion involves choices. Uncertainty is never the end goal. It’s more like a vehicle and an approach to life. Most of the time it’s our fear of uncertainty that leads to paralysis. It’s not the uncertainty itself. If we approach uncertainty knowing it’s a space of possibilities, or as another psychologist told me, an opportunity for movement, then we can be present in the moment and start investigating and exploring.

But if we’re afraid of uncertainty, we’re more likely to treat it as a threat. And if we’re more tolerant of uncertainty, we treat it as a challenge.

Sean Illing

You cite some research about fear of the unknown as at least one of the root causes of things like anxiety and depression. It certainly makes intuitive sense, but what do we know about that relationship?

Maggie Jackson

This is a very new but rising theoretical understanding of mental challenges in the psychology world. More and more psychologists and clinicians are beginning to see fear of the unknown as the trans-diagnostic root, or at least a vulnerability factor, to conditions like PTSD and anxiety. But by narrowing down treatments to just helping people bolster their tolerance of uncertainty, they’re beginning to find that might be a really important way to shift intractable anxiety.

There’s one gold-standard peer-reviewed study by probably one of the world’s greatest experts on anxiety, Michel Dugas. He found that people who were taught simple strategies to try on uncertainty, their intractable anxiety went down. It also helped their depression. And then other studies with multiple different kinds of populations show that focused strategies about uncertainty boost self-reported resilience in patients with multiple sclerosis, who are dealing with a lot of medical uncertainty.

Sean Illing

It’s just a fact of life that things will change and the world won’t conform to our wishes, and so I feel like we end up going one of two ways: We either embrace the limits of our knowledge or we distort the world in order to make it align with our story of it, and I think bad things happen when we do the latter.

Maggie Jackson

That’s right. I think it’s also backbreaking work to continually retreat into our certainties and close our eyes to the mutability of the world.

I had a real epiphany when I was doing some writing about a Head Start program that teaches people from very challenged backgrounds, both parents and preschoolers, to pause and reflect throughout their very chaotic days. And it seems like something that doesn’t have much to do with uncertainty, but they were basically inhabiting the question even though it was a very difficult thing to snatch these moments of reflection within their lives.

In parallel to that, there’s a lot of new movement to understand the strengths of people who live in lower economic situations that are often chaotic. What was amazing to me is that I realized how much I grew up expecting that stability and predictability was just an entitlement. That this is the way we should live, that this is the skill set you need to adapt in order to thrive. Many of us have airbrushed out of our psyches the ability to live in precarious situations.

Sean Illing

So when someone is confronted with the feeling of fear that comes with not knowing, how should they sit with that? What’s your practical advice?

Maggie Jackson

Well, first, you can remind yourself that this is your body and brain’s way of signaling that there’s a moment when the status quo won’t do. That this might be uncomfortable, but it’s not a situation or a state of mind that prevents forward progress — it’s actually propelling you forward.

It’s truly changed my life writing this book, and it’s taken away a little bit of the fear that I might carry into new situations — from giving a speech to being in the presence of someone who’s very upset. I used to want to just offer a solution, and give that silver lining, and get that moment over with and get them on the road to happiness. And now I feel much more patient. And with that comes the ability to follow a path down an unexpected road, or even take a detour.

February 18th 2024

Related Condition Centers

I’m a Neurologist. Here’s the One Thing I Do Every Day for My Long-Term Brain Health

If you’re worried about cognitive decline, add this to your routine.

Medically reviewed by Jessica Ailani, MD

February 14, 2024

Everything you do—walking to your yoga class, making your favorite latte order, talking to your bestie, and just getting through the workday—happens thanks to your brain. Your brain is the control center for your entire body—it’s how you get shit done. So how can you take care of such a beautifully complex and integral part of your body and keep it in great shape for as long as possible?

Lara V. Marcuse, MD, a board-certified neurologist and codirector of the Mount Sinai Epilepsy Program at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, shares the one thing she does every day (or almost every day, because life gets busy, folks!) to keep her brain healthy. As a bonus? It’s fun.

Pick up a difficult new skill, even if you suck at it.

“I started playing piano in my mid-40s,” Dr. Marcuse tells SELF. It all started by chance when her son began taking lessons: “I took his lesson book on the sly one night before bed, and I was totally enthralled by it,” she says, though she admits she found the songs themselves hard to get into at first. “I’m a 1980s New York City club kid. I grew up on a steady diet of house music, and I never liked classical.” It’s been seven years since she first gave playing a Chopin piece a shot, and she hasn’t looked back since. “[Playing piano] helps me get into [the] nooks and crannies of myself—and into my spirit,” she says.

Taking up a hobby that’s unfamiliar and even difficult forces your brain to exercise new or rarely used neural pathways, and that can help prevent cognitive decline and even protect your brain against Alzheimer’s disease, a type of dementia that leads to memory loss and an inability to complete daily tasks. Keeping your brain active makes neural pathways strong—and the opposite is true if you’re not finding ways to engage your mind.

.jpg)

WATCH10 Minutes Of Guided Meditation For Muscle Tension

Most Popular

- How to Get a Good Night’s Sleep When You Have Chronic Back PainBy Ashley Abramson

- Why You Should Never Squeeze or Pop an HS CystBy Sarah Klein

- 7 Small but Effective Ways to Relieve Back PainBy Julia Ries

Playing an instrument, in particular, engages every facet of your brain. If you’ve ever looked at a sheet of music, it’s basically like reading a different language. Your brain goes through a bunch of hoops to figure it out. (Anecdotally speaking, as a former cello player, I can attest to the fact that reading music is no joke; I recall spending hours trying to understand a simple string of notes.) When you sit down to play the keys or strum a guitar, your brain is hard at work trying to tell your hands what to do.

Musical activities trigger the auditory cortex (a.k.a. the part of your brain that helps you hear) and areas of your brain that are involved in memory function. According to a 2021 review published in Frontiers in Neuroscience, performing music is rewarding and makes you want to continue your musical training practice. It also improves brain plasticity, which refers to ways your brain changes in response to external or internal factors, like a stroke or another traumatic brain injury, and how the brain adapts afterward. Learning how to play might result in structural and functional changes in your brain over time, exactly because it takes a while to learn.

Your brain-bolstering activity of choice doesn’t have to be music-based, Dr. Marcuse says, as long as you’re interested in whatever you’re doing enough to want to commit to it. You can paint, try tai chi, or learn how to interpret tarot cards.

The other key piece of this is making sure that your new hobby involves some amount of challenge. “It has to be something a little new that’s a little hard,” Dr. Marcuse says. Passively watching the latest episode of The Bachelor won’t cut it, because you need your brain to be active, take in new information, digest it, and then put it back out there.

While you might feel that learning a new skill feels daunting, that’s the point! According to Dr. Marcuse, you don’t have to be good at the activity to protect your brain: “I never took music lessons as a kid. I’m not really good at it. I never will be,” she says.

And despite not being the next Mozart, she says that playing the piano adds some color and levity to her days, in addition to protecting her brain. “I really need that in my life—I have a very stressful job,” she says. “It makes me feel that the world is sort of full of beauty and hope.”

How to make a new skill a regular part of your life—and why it’s great for your brain

You don’t have to do the activity every single day, or even for a very long time. “Just try to do it frequently, and don’t do it for very long,” Dr. Marcuse says. Sometimes all she has time for is a few bars or a couple of scales—do whatever works for you, as long as you stay somewhat in the swing of a routine.

Most Popular

- How to Get a Good Night’s Sleep When You Have Chronic Back PainBy Ashley Abramson

- Why You Should Never Squeeze or Pop an HS CystBy Sarah Klein

- 7 Small but Effective Ways to Relieve Back PainBy Julia Ries

A 2020 research study found that increasing the frequency with which you engage in your hobby (like doing crossword puzzles, playing board games—or an instrument—or reading the newspaper) decreases cognitive impairment and depressive symptoms in older populations. In other words, doing your hobby more often will be better for your overall well-being. Practice not only increases the speed at which you can perform a task, but it also improves your accuracy. Research theorizes that when you attempt an activity for the first time, specific brain regions are activated to help you complete the task; this creates new neural pathways as your brain stores all this new information in your memory as you continue practicing your skill over time.

Consistently training your brain will help boost your cognitive processes over time, because the myelin sheath—the layer of protein that coats your nerves—thickens. A plumper myelin sheath helps your brain transmit and process information more efficiently. (An added bonus of practicing: Even though the word routine sounds dull as all get-out, maintaining one can reduce your stress levels and make you happier in general.)

Whether you decide to take a cooking class or learn Spanish, try a new hobby that really speaks to you. “Everything you do to protect your brain is going to make your life better,” Dr. Marcuse says. Bearing that in mind: I think it’s time to pull out the ol’ cello that’s been collecting dust in my closet.

Related:

- How Even a Little Daily Movement Can Help Reduce Your Risk of Dementia

- 3 Ways to Take Care of Your Mental Health as You Get Older

- What Does Self-Care Look Like When You’ve Got a Brain Injury?

February 1st 2024

‘My life will be short. So on the days I can, I really live’: 30 dying people explain what really matters

Facing death, these people found a clarity about how to live

by Philippa KellySat 27 Jan 2024 10.00 GMTLast modified on Sat 27 Jan 2024 21.21 GMT

‘I don’t sweat the small stuff any more’

Mari Isdale, 40, Greater Manchester, England

In 2015, Isdale, then 31, was diagnosed with stage four bowel cancer and given 18 months to live. Despite a period of remission and 170 rounds of chemotherapy, the disease has since spread to her lymph nodes.

I always thought, “I’ll get my career sorted, then we’ll get married, have children, go travelling.” And then cancer happened. You grieve for your future self. Your imagined children and your career. If I died tomorrow, what I’d be saying on my deathbed is I regret not spending enough time with my family. So that’s what I focus on.

I have a “Yolo list” of things I want to experience in life and my husband and family work very hard to ensure we do as many of them as possible together. They’ve taken me snorkelling in the Maldives, hot-air ballooning over Cappadocia and snowmobiling in Iceland. We’ve stayed in a cave hotel, seen the pyramids, the Colosseum, and flown in a helicopter over New York. We’ve hand-fed tigers, taken the Rocky Mountaineer train, been paragliding and seen the tulip fields of Holland.

My life is most likely going to be short, so on my good days, when I’m well enough, I really live. I go out and do anything I want: for a nice meal, to the theatre, cinema or an escape room.

My illness has changed the way I prioritise things. Although I loved my career as a doctor, it often meant long hours, missing out on Christmases and birthdays, exams, stress. Giving that up is a big sacrifice, but it’s one I’m willing to make to gain more time with my loved ones. It is ironic that it took being told I was dying before I really started living.

Anything that doesn’t make my heart sing is less important to me these days. I don’t sweat the small stuff any more. Life is too short for cleaning. The laundry pile will wait. And if I want to eat a piece of cake, I damn well do.

‘Don’t waste energy fighting’

Michèle Bowley, 57, Basel-Stadt, Switzerland

After Bowley found a lump in her armpit in summer 2020, a biopsy revealed breast cancer. The disease spread to her lungs, liver and bones, and in late 2021 she was given a prognosis of three to six months.

Accept yourself and your situation. Don’t waste energy fighting. The most important things in life are other people. Pay attention to your needs and do what makes you happy. Do something creative, learn something new, get involved in something that matters to you. Enjoy your life to the last breath.

I have no regrets. I’ve always done what was important to me and have reached my full potential regardless of what others expected or thought of me. I’ve had a fulfilled life; I’m ready to go.

‘Having a sense of purpose brings joy’

Mark Edmondson, 41, Sussex, England

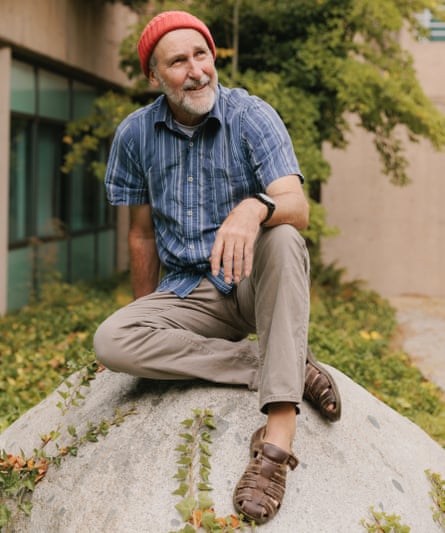

Mark Edmondson: ‘I’ve never been happier.’ Photograph: Lydia Goldblatt/The Guardian

In 2017, Edmondson was diagnosed with colon cancer. After doctors also discovered more than 30 tumours in his liver, he was given a year to live. He has since undergone more than 140 rounds of chemotherapy and over 30 operations.

Prior to getting cancer, I had ambitions of becoming a managing director or CEO; I wanted to achieve something in my career. Within hours of the diagnosis, that disappeared. I don’t care for work any more, but I believe strongly in having a sense of purpose, something to motivate and distract you, and bring joy and satisfaction. I get that from the business I started: a support service for anyone facing adversity. If someone had said, two years into my treatment, “Do you feel able to support other people through their diagnosis?”, I would have said no way. But as time has passed I do, and I’ve spoken to more than 100 people. I love coaching and mentoring. I’ve never been happier.

I lead every session with this quote and loop back to it at the end: “It’s not what happens to us, but how we react that defines who we are.” So how do you want to be defined? Cancer or no cancer, that question should dictate how you live.

I’m a big believer in being as honest and open as possible. Men are notoriously bad at sharing our feelings, but I want to change that for my boys.

We get pushed along in this world by consumerism, but it doesn’t matter what car or house we have, as long as we’re comfortable. What really matters is love, relationships, kindness, caring for people, being around people. I want to create the best relationships I can, and live the happiest life I can, because I no longer know what my timeframe is.

‘It’s not about the quantity of time I’ve got, it’s the quality’

Chris Johnson, 44, Tyne and Wear, England

In 2019, Johnson was diagnosed with a rare gastrointestinal cancer. In 2020, hundreds of small tumours found on his liver led to a prognosis of two to five years.

I’ve got limited time, so I’d rather be doing things with family and friends, and having a positive impact on the world around me. I’m not in the office wearing a shirt and tie any more. In 2021 I was running marathons, and last year I completed the National Three Peaks Challenge.

Fundraising has been the main driver but exercise also helps with the side-effects of my treatment, though as that progresses, it’s becoming harder to do long distances.

I still care about politics, the climate and my football team, but I don’t get stressed about them any more. It’s not about the quantity of time I’ve got it, it’s the quality.

People talk about beating cancer or winning. I’m never going to beat cancer, it’s not an option. At some point it will kill me. But until then, how I live my life is my version of winning.

‘Cancer sorts out what really matters’

Siobhan O’Sullivan, 49, New South Wales, Australia

After feeling unwell for two weeks, O’Sullivan was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in August 2020. It had already spread beyond her ovaries, and did not respond to chemotherapy.

I have a lot of colleagues and friends around the world, and people have mailed me gifts from every corner of the globe. An English friend flew out to see me for three days; he spent longer in the air than with me. This is the kind of generosity of spirit that people have shown me and it’s been very moving.

Cancer has been extremely effective in sorting out what really matters and what doesn’t. I was always a very busy person, and if I was meeting someone for lunch at 1pm and they strolled in at 1.20, I might have been irritated. Now I’ve realised none of that matters. I would love to have had this insight and these connections without having to go through this cancer bullshit. But I don’t think there’s a shortcut to it.

Siobhan O’Sullivan died on 17 June 2023.

‘Sharing your feelings helps’

Harry Soko, 59, Salima, Malawi

Harry Soko: ‘When I’m alone, I wonder why I got it.’ Photograph: Thoko Chikondi/The Guaridan

In July 2020 Soko noticed a pain in his right thigh. A year later he was diagnosed with skin cancer, which will significantly shorten his life: a 2014 study at the care centre where he is being treated found only 5% of patients with the condition live more than five years.

Normally we say, “If you are suffering from cancer, the immediate result is death.” So my family accepted it. The community accepted it. When I’m alone or sleeping, it comes to me: “Why am I suffering from cancer? How did I get it?” It takes time to accept. But if you share your feelings with others, you become free. You have no worries.

‘My illness stripped me of my fears’

Juan Reyes, 56, Texas, US

Reyes was diagnosed with ALS in 2015; he’d had symptoms for two years, and the average survival time is three. In the next six months he became a wheelchair user; he has since lost the use of his hands.

I’m very much an introvert, quiet and reserved, and afraid of public speaking. Having to live with ALS has stripped me of many of my fears. I’ve always had a very silly streak with close friends and family, and now I use that as a power, to entertain and educate through comedy.

The first time I did standup was in October 2019, at a fundraiser for ALS I’d organised at a local comedy club. I didn’t intend to do it, but as I was opening the evening, I took a chance. Afterwards I felt incredibly alive.

I also went skydiving six months after diagnosis. The first step out of the aircraft took my breath away. The rush of air was deafening, then I was suspended above the landscape. The serene silence, interrupted by the rustling of the canopy, was life-altering. I’m so glad I experienced this. I’m dying, so what is there to fear?

‘Stop worrying about having a good job or needing a big house’

Caroline Richards, 44, Bridgend, Wales

Her son was 16 months old when, in 2014, a swelling in Richards’s stomach was diagnosed as bowel cancer. She was told that, with successful chemotherapy, she would probably live for two years.

These past nine years have been really good, probably better than if I hadn’t had cancer. Different things became a priority: spending time together rather than worrying about having a good job or thinking you need a big house.

In a way I feel lucky – I could have died when my son was three or four. I feel as if I’m living on borrowed time. But he knows me. He’ll remember me.

‘Find gratitude’

Tyra Wilkinson, 50, Ontario, Canada

A family history of breast cancer meant that when Wilkinson was diagnosed with the disease in 2015, she had already made plans for a mastectomy. Seven years later, the cancer had returned and spread to her spine, making it incurable.

My husband and I had plans for when our kids were grown. We have always said we’d be the most fit grandparents, playing with our grandkids on the ground. Even if I’m alive I won’t be able to be that grandparent, because I’m just not capable of doing that stuff now.

Find the gratitude for what you have because it can always – and will always – get worse. Be grateful for all the things that are going your way right now.

‘Go to the parties. Stay out late’

Amanda Nicole Tam, 23, Quebec, Canada

Amanda Tam: ‘Don’t hold back.’ Photograph: Andrew Jackson/The Guardian

After noticing symptoms in January 2021, Tam was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) that October – five days before her 21st birthday.

I wish I had gone out more with my friends. I wish I had gone to parties and stayed out late. Living life free-spirited is something I feel I missed out on, and I regret that I didn’t take advantage of that when I was younger. Life is short and you should live it how you want, regardless of what people think. Don’t hold back. Say what you want to say and do what you want to do.

‘Have a goal. Don’t accept defeat’

Mark Hughes, 62, Essex, England

More than 20 years ago, pneumonia led to the discovery of a tumour in Hughes’s lung. Surgery was successful, but the cancer had spread to his lymph nodes. In 2010, a rare form of the disease, which is now terminal, was found in his bones.

It’s about having a goal, a purpose, setting your sights somewhere. I won’t be beaten down or accept defeat. The only way is forward, and there’s always a finishing post I’m aiming for. If you get knocked down, get back up, brush yourself down and go again. That’s what keeps me going.

‘You are enough; you make a difference’

Chanel Hobbs, 53, Virginia, US

At 37, Hobbs found herself unable to run without falling; she was diagnosed with ALS and given a life expectancy of up to five years. She is now dependent on a ventilator and feeding tube.

Before my diagnosis, I was very independent. I prided myself on doing things on my own. But I’ve learned that others really want to assist, and it brings them joy knowing they can make a difference, however small.

I always used to plan every single facet of my life. I wish I had been more spontaneous and done things when they crossed my mind. For example, looking out the window and wanting to go for a walk, but doing housework instead. How I yearn for a walk today. Now I give myself grace. I have learned not to compare myself with others. Find what makes you feel meaningful. Remember: you are enough, you are human, and you make a difference.

‘No matter how you feel, get up, get dressed and get out’

Simon Penwright, 52, Buckinghamshire, England

In the early hours of 24 January 2023, Penwright was woken by an unpleasant taste and smell. Doctors discovered three brain tumours, one covering half of his brain. He was diagnosed with an aggressive form of glioblastoma and given less than 12 months to live.

It would be so easy to wake up in the morning and just lie in bed. I’m not a gym person, but when I’ve done a bit of exercise, I feel fantastic. No matter how you feel, get up, get dressed and get out.

If you’re OK one minute, then have a cardiac arrest and you’re gone the next, your options are taken away. So I guess I’m grateful that I can get organised and make the most of my relationships. I’d take this route every time.

‘I’ve stopped caring what others think’

Sukhy Bahia, 39, London, England

Sukhy Bahia: ‘I want my kids to know milestones are bullshit.’ Photograph: Lydia Goldblatt/The Guardian

Diagnosed with primary breast cancer in 2019, Bahia was given the all-clear by her oncologist in March 2022. Five months later, she discovered the disease had spread to her bones and her liver.

I’m a single mum. It’s heartbreaking because you think you’ll be around for your kids for a really long time. My daughter is nine and my son is six, and I’m completely transparent with them about my health. I’m hoping to leave things for when I’m not here – birthday, graduation, wedding, new home, new baby cards, and a cookbook of all their favourite recipes. I’m also planning video blogs, giving advice on things they may not be comfortable asking anyone else, like consent and puberty.

I want them to know that they never have to impress anyone or try to fit in, and that milestones are bullshit. Nothing needs to be done by a certain age or time; you can always change what you want to do in life.

I’ve stopped caring what other people think of me. From my teens, I always wanted a full sleeve tattoo. Last year I decided to start one with the birth flowers of my children, to show how much they mean to me.

My kids love them; my parents aren’t over the moon, but they accept there are worse things I could be doing with my life.

‘Never create a new regret’

Kevin Webber, 58, Surrey, England

On holiday in 2014, Webber noticed he was visiting the bathroom a lot. Soon after he was diagnosed with prostate cancer and given four years to live.

I don’t have many regrets. Maybe I wish I’d taken my kids to school more. When they grow up, you realise that meeting you had at work, you could have probably moved it back an hour.

In that moment, when you know it’s over, I don’t want to look back with any remorse. You can’t change yesterday. Never creating a new regret is an important way to live your life.

I have three missions every day. Enjoy myself, but never at the expense of someone else. Try to do some good – and that doesn’t have to be raising 10 grand for charity; it can be smiling or giving someone a seat on the bus. And make the best memories, not just for you on your deathbed, so you can lie there and go, “Oh, that was great when I did that”, but for everyone else.

‘I realised what I really wanted to do’

Sophie Umhofer, 42, Warwickshire, England

In 2018, after 10 months of tests for conditions such as IBS and Crohn’s disease, Umhofer was diagnosed with bowel cancer, which had spread to other parts of her body. She was told she could live for three more years.

Initially I felt as if I had to cram the rest of my life into the couple of years I’d been given. I’ve written birthday cards and letters for my kids until they’re 21, preparing them for me not being here.

Obviously I wish it hadn’t been cancer that caused this, but I’ve changed so many things about myself. Before my diagnosis I would get very stressed out. I had this perfectionism when my kids were young that they had to have routines. I spent so much time being worried about things I didn’t need to do. And once I became a mum, I sort of gave up what I wanted to do.

I regret that I didn’t take action for myself a bit more. But this diagnosis meant that all of a sudden, I realised what I really wanted to do. When I was going through chemo I was trying to find things I could do to keep myself entertained, and I started watching motorsport. When I got a bit better I actually entered a competition and got through to the finals. I ended up getting a job in motorsport and now work full-time looking after a team. I wish everybody could see how much better life can be if we change the way we think.

‘Leave the damn house’

Arabella Proffer, 45, Ohio, US

Arabella Proffer: ‘You never know what’s going to happen.’ Photograph: Nancy Andrews/The Guardian

In 2010, Proffer was diagnosed with myxoid sarcoma. Ten years later, the rare form of cancer was found to have spread to her spine, lungs, kidney and abdomen. Told to get her affairs in order, she now plans her life two months at a time.

A year before I was first diagnosed, my husband had joked, “Hey, why don’t we cash out our retirement and follow Motörhead and the Damned on tour through Europe?” When I got the diagnosis, I thought, “We should have done that.”

My mantra is to leave the damn house, because you never know what’s going to happen if you do. No interesting story ever started with, “I went to bed at 9pm on a Tuesday.”

‘Just buy it. Do it. Go and get it’

James Smith, 39, Hampshire, England

In 2019, Smith noticed a twitch, then a weakness in his left arm. Two years later he was diagnosed with motor neurone disease (MND).

When I was told I’ve probably got only a few years to live, my wife was pregnant with our youngest. In the back of your mind you’re thinking, “Am I going to see them get married? Have kids?”

I did turn to alcohol, but it wasn’t doing me any favours; I was using it to block out what I didn’t want to think about, so I nipped it in the bud. Now I’ve come to terms with what I’ve got and I just take every day as it comes. I focus on what I can do, not what I can’t do. I had to give up my career as a barber, but I’ve found a new passion in creating my podcast, which shares my story and those of others to raise awareness of MND. Talking to others and relating to people going through the same situations as me is like therapy.

It’s horrible to say it takes a terminal illness to actually live life, but when I hear people going, “I’d love to do that”, I realise getting diagnosed has put a different perspective on life. I used to think, “I won’t buy that because I don’t know what’s around the corner.” Now it’s just buy it, just do it. If you want something and can afford it, go and get it. If you want to do something and you’ve got the means, go and do it.

‘I soon realised what I liked about life’

Ali Travis, 34, London, England

At 32, Travis began experiencing severe headaches. After an MRI revealed a mass the size of an orange on his brain, he was told he had a glioblastoma and his life expectancy was 12 to 14 months.

Last year was the best year I’ve had because in a very, very short space of time, I realised what I liked about life. It’s the closeness of relationships, old friendships. And, for me, being a geek.

If I’d been hit by a bus, I’d have been a stressed guy with a load of problems who couldn’t see past the end of his nose. So, despite all the surgeries, the constant chemotherapy, the radiotherapy, I would choose this route.

‘Look after yourself first’

Sonja Crosby, 55, Ontario, Canada

Sonja Crosby: ‘Cancer focused me.’ Photograph: Jessica Deeks/The Guardian

In 2012, doctors discovered a tumour on Crosby’s left kidney. She was diagnosed with a rare form of cancer, and most organs were removed from her left side. In 2017 she was given six months to live.

Cancer focused me more precisely than anything else I can think of. When my doctor told me I had a few months left, I said, “Can we put that off another six months? I have this big project at work I want to finish.” He said, “No, you have to be your priority now, not work.”

You can’t manage all aspects of your life. I’ve realised it’s not selfish to look after yourself first, that your friends and family will do a lot more if they know you’re open to receiving help.

‘My favourite saying is: it is what it is’

Rob Jones, 69, Merseyside, England

In October 2012, Jones was told he had bowel cancer that had spread to his liver. He had 27 rounds of chemotherapy.

I’m not a bucket list person; I don’t go through life saying, “I wish I’d done that.” My wife says I’m one of the worst people in the world to buy anything for, because if I want it, I get it. It’s the same in life, if we can afford it. But I’ve never had dreams of doing a world cruise or a flight to America. I’m a home bird really.

I read once that cancer victims are lucky in life, because they generally have a timeframe of when they’re going to die. They can put their life in order, say goodbye to loved ones, ignore all the people they’ve tolerated to be polite. Whereas people who have a massive heart attack and die on the spot, they don’t have that opportunity. I sort of get that now. But I’m not allowed to talk as if the end of the world is nigh, because everybody thinks I’m invincible. Of course, none of us are.

My favourite saying is: it is what it is. If we had the choice, we’d all live a long, happy life. But when would we choose to die? There isn’t a convenient time.

Rob Jones died on 28 July 2023.

‘What’s the point of earning, earning, earning, if there’s no joy in your life?’

Jules Fielder, 39, East Sussex, England

In November 2021, Fielder was diagnosed with double lung cancer, then shortly after told the disease had spread to her spine and both sides of her pelvis.

You get caught up in that world of work: pay your bills, eat dinner, sleep, repeat. But now I truly feel very different about money. What’s the point of earning, earning, earning if there’s no joy in your life? When I watch really power-driven people who want more and more, I want to tell them it’s the small things in life that are beautiful. We live in quite a toxic world, but it’s your choice what you expose yourself to. I get up, I walk my dog, I listen to every single bird that chirps. I’m grateful for that.

‘Be authentically you’

Mike Sumner, 40, Yorkshire, England

Mike Sumner: ‘There are always positives.’ Photograph: Lydia Goldblatt/The Guardian

While on TV show First Dates in March 2020, Sumner noticed a loss of movement in his foot. Eight months later he was diagnosed with motor neurone disease. He has since married his date, Zoe.

I don’t waste time now. Life is too short to be doing any shit you don’t want to. Concentrate on making the memories you want and never say no, never make excuses. Do things you’ve always wanted to do. We went to Los Angeles to see the Back to the Future set at Universal Studios. I’ve been meaning to go for years. It was our little pilgrimage.

In the short term I keep positive by thinking about weekends, because we often go away and do something fun – next weekend we are going to a classic car show. In the longer term, I look forward to our next holiday – we always go to Orlando. When I feel the warm air on my skin, and hear the crickets of an evening, it lifts me emotionally.

Day-to-day I look forward to Zoe coming home from work so I can give her a cuddle. I look at my model car collection and think about the happy memories I have of driving. When I feel a bit low, I treat myself to something nice to eat – pizza, a burger or a battered haddock – while I can still enjoy food.

You have to be authentically you. But try not to moan because there’s always someone worse off than you. Focus on the positives; there are always some. For example, I’m married to Zoe.

‘Keep things simple’

Alec Steele, 82, Angus, Scotland

In 2020, while in hospital for a routine checkup, Steele collapsed. Tests revealed idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis – which causes scarring on the lungs and leads to difficulty breathing – and he was given a prognosis of one to five years. He now requires a 24-hour oxygen supply.

The first six months after diagnosis were dreadful. I was trying to get all my affairs in order, and I told my medical team I was determined to have one last game of cricket. The physiotherapist and I worked as hard as we could, and in late April 2021 I got my game, wicketkeeping with oxygen strapped to my back. A photographer took a photo and put it on the internet. It is now displayed at the Oval, next to Ben Stokes’s photo. Last year I had 16 games, which has just been wonderful.

I’ve realised I have to keep things as simple as possible. I soon learned that negative thoughts were destructive and I trained my mind to work out those you can do something about and those you can’t. If it’s the latter, discard them. If you can do something, work out what and get started to tackle the problem.

‘Switch every negative to a positive’

Kate Enell, 31, Merseyside, England

In July 2021, less than a month after finding a lump in her breast, Enell, then 28, was diagnosed with stage four breast cancer. It had spread to her liver and bones, and has since moved to her brain.

For two days after being diagnosed I locked myself in the bedroom; I didn’t see or speak to anyone. But on the third day I thought, “Wait – if I’ve only got a short timescale, do I really want my little boy to see me miserable?” Now I just try to do as much as I can while I’m here. I’m quite good at switching my brain now. Say I get upset about not being able to have more children, I switch it round and think, “Well, I am a mum.” Whenever there’s a negative, I try to switch it and keep positive.

I feel like I’ve had some of my best times in the first few years of my diagnosis, because it makes you home in on what’s important. Everybody around me has made more of an effort, we’ve done lots of family events. It’s made us realise that what’s important is spending quality time together.

‘Success, status, reputation – they are not important’

Ian Flatt, 58, Yorkshire, England

Ian Flatt: ‘What’s important is to find joy every day.’ Photograph: Lydia Goldblatt/The Guardian

Flatt had always led a very active life, but in April 2018 he began struggling with severe fatigue. By the following March he had been diagnosed with MND and he has since lost the use of his legs.

I can categorically say that the things I valued and felt were important are not important. Success, status, reputation – they pay the mortgage, but I think I lost myself a little bit in all that. I’m much more emotional and empathic now. I’ve always been a reasonably popular guy, I have friends that go back 30-odd years, but I’ve never had the depth of friendship that I have now. Or maybe I had it and didn’t appreciate it.

What’s important now, every day, is to find some joy. I look out at the birds, the trees – I’ve a favourite one I can see out of my bedroom window. Through being a bit reckless, I lost the use of my legs sooner than I would have. I remember accepting that and thinking, “OK, I’m not going to walk, so let’s go out in the tangerine dream machine [his off-road wheelchair].” We went out, had a pint of Guinness, and now my memory of that day is a joyful one.

‘Your energy is valuable’

Daniel Nicewonger, 55, Pennsylvania, US

In May 2016, after he started struggling to take a full breath, Nicewonger was told he had colon cancer that had spread to his liver. The prognosis was two years.

It took this to clarify what’s really important. You get very good at saying, “No, I choose not to invest energy and time in this, because my energy and my time is just that much more valuable.” If I could have understood that at 30, I’d have moved through life in a totally different way. But that’s unrealistic. Wisdom is wasted on the young.

‘Don’t mess around. Be direct’

Angus Pratt, 65, British Columbia, Canada

Angus Pratt: ‘I discovered self-confidence.’ Photograph: Rachel Pick/The Guardian

A lump on Pratt’s chest in 2018 led to the discovery of breast and lung cancer. He was given a 5% chance of living to 2023.

I had my diagnosis in May, my wife was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer at the start of October, and by the middle of November she was dead. I had to ask myself the big question: am I leaving behind what I want to leave behind?

I’ve taken on writing assignments, helping scientists translate research into patient-friendly language. Recently I was asked to contribute a painting to an auction, and I was surprised people would pay for my art. One of my joys is a local poetry group that meets in the park. Sometimes we have an open mic. I guess I’m trying to say I’m a poet, too.

I’ve discovered self-confidence. I really don’t care what people think about me any more; it’s not important because I’m going to die. I don’t have time to mess around, so I’m going to be direct. That’s stood me in good stead.

‘I should have trusted myself more’

Henriette van den Broek, 63, Gelderland, the Netherlands

When Van den Brook was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2008, the disease had already spread to her lymph nodes. She was well for a number of years, but in 2020 she discovered that the cancer had spread to her stomach and was terminal.

Every day when I work as a nurse, it feels like a party for me. I realise how meaningful I can still be to other sick people. I enjoy the little things more, dare to have the difficult conversations.

It’s a pity I’m only finding that out now. I feel like I need to catch up on this in a hurry and get the most out of life. I’m discovering the things I’m good at, but I’d have liked to discover them sooner. I should have trusted myself a lot more and been less insecure. I only have the guts now.

‘Treat every smile like it’s your last’

Ricky Marques, 42, St Helier, Jersey

In summer 2022, Marques began to lose weight. In November, a CT scan led to a diagnosis of lung cancer. The disease, which has spread to his bones and lymph nodes, was so advanced that he was given a prognosis of weeks or months.

When I was younger I had a son, and when he was eight, he died in a car accident. My life collapsed and I thought, “How am I going to recover?” When I was diagnosed with terminal cancer I thought, “What else am I going to get? Didn’t I already have my share of bad luck? Don’t I deserve to live?”

The lesson I’ve learned is every time someone smiles at you – a little touch, a little gesture – look at it like it’s the last one because, guess what? Maybe it is.

January 29th 2024

Stoic Freedom (Deep Resistance Part 4)